Événement Conférence

Science-Policy Panel on Chemicals, Waste and Pollution Prevention: Building the Linkages from Science to Action | BRS COPs 2023 Side Event / SPP-CWP Series

02 Mai 2023

13:15–14:45

Lieu: CICG | Room B & Online | Webex

Organisation: Groupe de travail spécial à composition non limitée chargé d’examiner la création d’un groupe d’experts sur l’interface science-politiques au service de la gestion rationnelle des produits chimiques et des déchets et de la prévention de la pollution, Geneva Environment Network

This side event to the 2023 BRS COPs is part of the Science-Policy Panel to Contribute Further to the Sound Management of Chemicals and Waste and to Prevent Pollution Webinar Series aiming to building bridges and promote collaboration and knowledge sharing between and among stakeholders, and to raise public awareness about the OEWG preparing proposals for the establishment of the panel. The webinar series is co-organized by the Secretariat of the OEWG and the Geneva Environment Network.

About this Event

At UNEA 5, countries agreed to establish an independent, intergovernmental science-policy panel to contribute further to the sound management of chemicals and waste and to prevent pollution. An ad hoc open-ended working group (OEWG) process has been initiated to prepare proposals for the panel. As set out in the UNEA 5 resolution, the panel will support countries to take action on chemicals, waste and pollution, including to implement various international instruments such as MEAs, by providing policy-relevant scientific advice. The Panel will also further support relevant MEAs, other international instruments and intergovernmental bodies, and other relevant stakeholders in their work.

The OEWG concluded its first session on 30 January to 3 February 2023 in Bangkok, Thailand, with a particular focus on the scope and functions of the panel and intersessional work. One key document to be prepared is on relationships of the panel with relevant key stakeholders, especially the chemicals and waste MEAs.

This side event to the 2023 BRS COPs provided an interactive platform to seek stakeholders’ input on relationships of the panel with relevant key stakeholders, particularly with regard to how to build linkages from science to support action. It sought countries’ view, particularly developing nations’, on their needs for such linkages. It invited the secretariats of the BRS conventions, IPCC and IPBES to learn from their experience with bridging science to action, particularly how the existing science-policy bodies relate to the respective conventions on climate change and biodiversity. The exchanges at the side event informed the development of working documents for OEWG 2 in December this year.

Road to OEWG 2 Webinar Series

This side event is part of the Science-Policy Panel to Contribute Further to the Sound Management of Chemicals and Waste and to Prevent Pollution Webinar Series.

As a follow-up of the resumed first session of the OEWG, a series of webinars, co-organized by the Secretariat of the OEWG and the Geneva Environment Network, was launched. The webinars aim at building bridges and promote collaboration and knowledge sharing between and among stakeholders, and to raise public awareness about the OEWG preparing proposals for the establishment of the panel.

Speakers

Kevin HELPS

Principal Officer, Secretariat of the OEWG on a Science-Policy Panel on Chemicals, Waste and Prevention of Pollution, UNEP | Moderator

Elizabeth MREMA

Deputy Executive Director, UNEP

Carlos MARTIN-NOVELLA

Deputy Executive Secretary, BRS Secretariat

Ermira FIDA

Deputy Secretary, IPCC Secretariat

Anne LARIGAUDERIE

Executive Secretary, IPBES Secretariat

Francisco Nelson DE ALMEIDA LINHARES JÚNIOR

Deputy Head, Division of Environmental Policy and Sustainability, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brazil

Moleboheng PETLANE

Environment Officer, Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Culture, Lesotho

Abbas TORABI

Counsellor & Interim Focal Point for Chemicals Conventions, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Islamic Republic of Iran

Highlights

Video

The event is livestreamed from CICG and via Webex.

Livestream from the CICG.

Summary

Opening Remarks

Elizabeth Maruma MREMA | Deputy Executive Director, UNEP

We are all living in the middle of the triple planetary crisis of climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss. These are the biggest threats facing humankind and the natural world. Each element of the triple crisis is deeply connected to each other; therefore, we need to address them together.

I’m delighted that science helps us to understand the complex interactions between human activities and the environment. Science can further help us to identify the most effective, holistic solutions to mitigate the impacts of the triple planetary crisis. But science cannot fully be effective without follow-up policies and actions: we need scientific evidence that is relevant to policy and accessible to policymakers. This can be made possible through science-policy interfaces that work to translate scientific findings into policy-relevant information. They are platforms for dialogue, communication, and collaboration between scientists, policymakers, and other stakeholders.

We have already seen the impacts of IPCC and IPBES on global climate and biodiversity governance: science-policy interfaces in action. This is why I’m pleased that UNEP has been asked to help member states to establish the science-policy panel on chemicals, waste, and pollution prevention.

Mismanaged chemicals in waste can be catastrophic. We have seen this through diseases caused by PCBs and mercury poisoning. We’ve seen in acute poisoning of hazardous and toxic waste, such as the one carried by the derailed Ohio train. We have also seen plastic pollution around the world. The goal of the SPP is to make important contributions to help us better manage such hazardous situations and address the pollution crisis by providing that policy-relevant scientific evidence and bases.

The panel’s success will depend on collaboration and cooperation with other entities like the World Health Organization and relevant multilateral environmental agreements and existing science policy panels. We are all determined to contribute to the development and design of a well-functioning science-policy panel.

Experience shows that a strong relationship between the panel and its key stakeholders is the major determinant of the panel’s overall success and effectiveness. We are fortunate to be able to grow insights from existing science-policy panels. We also have legally binding agreements such as the Paris Agreement, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the BRS Conventions that all provide important legal frameworks for global action. Establishing the strong links between these instruments will assist us to ensure the panel’s policy salience. Such links can also inform and ensure timely uptake of the panel’s work into policy so that international efforts are based on the latest science.

We must always also remember that addressing these crises must consider the range and varied needs and perspectives of all people and communities. We cannot forget the local communities and Indigenous peoples who must be empowered in these discussions in these decisions we take and actions on chemicals waste and pollution prevention by also engaging them, as they possess important local and traditional knowledge that can inform environmental protection, conservation, restoration, and climate change mitigation strategies.

By working together, throwing critical intelligence from science, and using the best available science-policy tools, we can create a more resilient and sustainable future for us all.

Building Linkages from Science to Support Action | MEAs and other instruments share experiences and perspectives

How do your institutions manage the interactions with key stakeholders, such as your relevant MEAs? What are the instruments that formalize that relationship? How do you work with academia, civil society, and industry?

Ermira FIDA | Deputy Secretary, IPCC Secretariat

IPCC is a 35-year-old organization established by UNEP and WMP with a mandate to provide a periodic assessment of the state of climate to the world. We operate in a world where you have a strong partnership between scientists who undertake the assessments and governments who set the rules on the ways and scope of their reports. The 195 member states sitting in the panel set the rules which are outlined under the Principles of the work of the IPCC.

One of the most interesting and relevant ones is the neutrality of climate policy in our reports. This means that IPCC produces reports which are policy-relevant but not policy-prescriptive. With the years, the IPCC has grown and has created its own profile. It has gone through cycles in 35 years with reports that are produced in every five to seven years, where we just concluded the Sixth Cycle.

Over six assessment reports, we have told the world where we stand, where the climate change challenge is at, and what is needed to be done by the governments. The way governments and scientists work together is what makes IPCC unique.

In the process of producing the reports, we engage with many stakeholders who engage with scientific community. In our latest set of data statistics from our sixth cycle, over 780 scientists have assessed more than 100,000 pieces of scientific literature, with over 300,000 review comments addressed.

This brings me to another important principle of IPCC which has to do with the nature of the review process that our reports go through: a back and forth between scientists and the review community which involves governments and experts from all over the world. These are assessments of peer-reviewed literature which have to be done or reviewed by a cut-off date for each and every cycle. IPCC doesn’t undertake any research or monitor data but builds on those that have been written by scientists all over the world. The review includes a 10-step process during the report preparation. For its sixth cycle, IPCC has three assessment reports with a working group for each (physics of climate; vulnerability, adaptation and impact; mitigation of climate change impacts).

When it comes to engaging with MEAs, everything we do is done mainly through the UNFCCC. This has a history which predates the birth of the Convention. It was the IPCC’s first assessment report that said that the world has now started facing a new challenge – climate change – and the said report underpinned the setting up of a text for negotiations in the first Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee of the UNFCCC, and ended up with the text of the convention after five years.

Other reports followed, such as one on the influence of human activities to global warming, which was followed by the Kyoto Protocol which would build on the need for the world had to reduce emissions. Each and every report that IPCC put out would be used by UNFCCC. The IPCC community would be invited by the UNFCCC to present reports and that culminated in the Paris Agreement, which used the fifth assessment report as the text of the Convent of the Paris Agreement setting very clear targets for reducing emissions between 1.5 and 2 degrees. Members of the UNFCCC then invited IPCC to produce a special report on what it takes to reduce emissions and stay below 1.5 degrees, which was known to be a game changer.

It is that moment in the IPCC’s history that culminates with actions emerging to address and try to stay within the two 1.5-to-2-degree limits.

Anne LARIGAUDERIE | Executive Secretary, IPBES Secretariat

The objective is to increase the policy relevance of IPBES, to increase the use of its products, and to enhance the impact of our work. But ultimately, what we are all looking for is to provide a stronger scientific basis for decision-making.

Main categories of stakeholders | We have six main categories of stakeholders:

- The governments, IPBES Members are the main stakeholders. IPBES currently has 139 governments. They are the members of the plenary which makes all the decisions. They approve the work program, and they are also invited to approve the summary for policymakers of our reports and the budget.

- MEAs with which IPBES collaborates. The Secretariat of IPBES has a Memorandum of Understanding with the Secretariat of five conventions – the Convention on Biological Diversity, on Migratory Species, the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, and also UNCCD. Another important point is that the chair of the scientific advisory bodies of these MEAs, as well as the chair of IPCC, are invited to participate as observers in the sessions of the Multi-Disciplinary Expert Panel, which is the scientific advisory body of the plenary of IPBES.

- Engagement with IPCC. IPBES, together with IPCC, produced a co-sponsored workshop report on the interaction between biodiversity and climate change back in 2021. There are no institutional arrangements for that to happen.

- Engagement with four UN partners – UNEP, UNESCO, FAO, and UNDP. That’s in the context of a collaborative partnership arrangement between the IPBES plenary and these entities. Each one of these four UN partners provides a number of contributions to IPBES. For example, UNESCO provides technical support needed to implement the approach for working with indigenous and local knowledge.

- Strategic partners. IPBES collaborates with a very limited number of strategic partners. Strategic partners require a memorandum of understanding. This is always a little bit complicated and time-consuming. Hence, IPBES restricts these to only those collaborations which involve an exchange of funds or staff. For example, IPBES has such an arrangement with IUCN, which supports the stakeholder engagement strategy of IPBES through providing one half-time staff member.

- IPBES also engages with hundreds of other stakeholders, and no institutional arrangements are necessary for this diverse engagement. For example, IPBES hosts many different types of webinars to engage non-governmental stakeholders. These can explain for example how to nominate experts, how to provide comments, or even how to use an assessment to increase the uptake of our reports.

IPBES also has two self-organized stakeholder networks. They are called the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services and the Open-Ended Network of IPBES Stakeholders. These two networks have as their main objective to co-organize the Stakeholder Day, which IPBES hosts ahead of each one of its plenaries. It’s a one-day event for stakeholders back to back with each plenary. Last year, for example, there were 800 participants in attendance. It is always quite popular. All of these stakeholders also play a role in providing input and comments to drafts. Furthermore, as part of this broad sixth category, a larger set of collaborative supporters are recognized on the IPBES website following selection by the Bureau of IPBES. In the context of their own work, they also advance the work of IPBES, such as by organizing capacity-building events to use the conclusions of a particular IPBES report, for example.

How do we work with the conventions? | The major partner of IPBES has been, and continues to be, the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). All of the assessments of IPBES, which just celebrated its 10-year anniversary last year and has produced 10 reports so far, have been requested among others by the CBD. All of these reports, once produced, have been formally considered by the CBD, first going through its substance, then ending up in its scope, and leading to COP decisions that oversee the use of IPBES work by parties and other stakeholders.

- For example, COP14 of the CBD had 14 of its decisions that mentioned the work of IPBES in a particular dimension of the World Program of the CBD. Decision 14-6, for example, which adopted a Plan of Action on Pollinators, is very largely based on the IPBES assessment of pollination, pollinators and food production.

- Another example is the Global Assessment of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services which came out in 2019. It’s been heavily used by the Open-Ended Working Group on the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework and it has inspired many aspects of the recently approved Global Biodiversity Framework. For instance, there are five targets associated with each of the five direct drivers of biodiversity loss that have been defined by the Global Assessment. The Global Assessment is heavily mentioned and cited in the decision on the new Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

- COP15 took a decision on the IPBES work program. It has requested new work for IPBES which will inform the implementation of the new framework. This includes new work on monitoring, which was one of the weaknesses of the previous agreement and new work on spatial planning and connectivity. This will help particularly with those targets that are area-based, such as the percentage of conservation and protection on land and at sea. There’s also a request for a second Global Assessment with many very specific requests.

How IPBES contributes to other MEAs? | IPBES recently completed a report on the sustainable use of wild species, which responded, among others, to a request from the CITES Convention. COP19 of CITES has considered this report and it led to a decision COP 20 to consider recommendations from the IPBES assessment as prepared by their two committees, the Animals and the Plants Committees, which are now working on the IPBES report in order to prepare these recommendations for COP 20.

To conclude, a major aspect regarding the link between the new panel and the conventions is really for the two mechanisms to have institutional links and for the two secretariats to work hand-in-hand. It is key for the convention to have the opportunity to make formal requests to the panel, and it is also key for the convention to formally consider the conclusions of each assessment report in its work. This provides the panel with the necessary legitimacy and policy relevance for its work to be used and to have an impact.

Carlos MARTIN-NOVELLA | Deputy Executive Secretary, BRS Secretariat

The Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions are science-based, multilateral environmental agreements. All the policy decisions taken by the governing bodies of these conventions are underpinned by valued scientific assessments. For example, decisions on establishing new chemical prohibitions, development of technical guidance and standards, and monitoring the effectiveness of the conventions are all heavily based on scientific knowledge. Examples of these scientific bodies providing the basis for decisions of these Conference of the Parties is the Persistent Organic Pollutants Review Committee (POPRC). This committee is comprised of scientific and technical experts who rely on scientific literature provided by the propelling countries as well as other parties and stakeholders. They assess the properties of chemicals, including persistence, bioaccumulation, potential for long-range environmental transport, and adverse effects. This determines whether the chemicals should be considered as POPs and if there is a need for global measures to be taken.

With regard to the Rotterdam Convention, the Chemical Review Committee evaluates the final regulatory actions provided by countries from a technical perspective. It determines whether chemicals and pesticide formulations have met or not met the criteria set out by the conventions and makes recommendations to the Conference of the Parties on whether to include these chemicals in its Annex III.

As for the Basel Convention, it operates slightly differently. We have an open-ended working group. This working group is not a pure scientific body, but it offers more of a technical advisory role.

It’s also important to mention the interface between our conventions, particularly the Stockholm Convention, and scientific knowledge. The Global Monitoring Plan for Persistent Organic Pollutants is an important component in evaluating the effectiveness of the Stockholm Convention. It provides a harmonized organizational framework for the collection of comparable monitoring data on the presence of persistent pollutants from all regions. The aim is to identify changes in concentrations over time, as well as regional and global environmental transport. It relies on scientists around the world who sample, analyze and process monitoring data to determine trends in the levels of POPs in various environmental media.

Within the three conventions, several technical guidelines have been developed and are updated periodically. In these cases, the guidelines are developed and drafted by groups of technical experts, all with a scientific background.

The Commission itself adopted, in 2017, a roadmap for further engaging parties and other stakeholders in an informed dialogue to enhance policy-science-action in the implementation of the conventions. The roadmap was then revised in 2019, and parties and others were encouraged to undertake actions that could promote the implementation of the roadmap.

Three main objectives were identified within the roadmap are listed as follows:

There are also relevant linkages, or interlinkages, between the chemicals and waste agenda and other agendas such as climate change and biodiversity loss. We are aware of reports from the IPCC referring to the impacts that incineration of waste may have, the impacts of different kinds of land use related to waste management, the brownfields, greenfields, and the impacts of climate change itself on the release of POPs that are encapsulated in the Arctic and then, due to melting, re-enter the atmosphere. There are a number of interfaces, and when we look at biodiversity, we don’t need to be deeply informed to understand the impact of pesticides on wildlife. Thus, there are many interfaces that we see and incorporate information from both the IPCC and the IPBES into our evaluations.

In our previous COP last year, the Secretariat received the mandate to participate in the meetings and contribute to the discussions and establishment of this new panel. We have a mandate from the BRS Secretariat to support the work and the negotiations on the new panel. A similar decision will be considered at this COP, and the other Secretariat is very excited about continuing this collaboration.

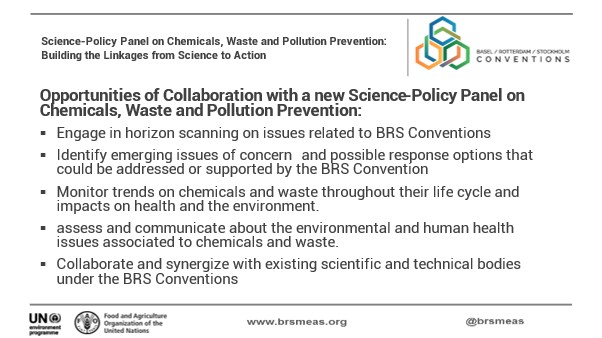

Opportunities of Collaboration with a new SPP on Chemicals, Waste and Pollution Prevention | Opportunities for further collaboration with the panel, once it’s established.

One might question the need for such a panel, given the existing scientific bodies, technical panels, and global monitoring programs. However, I can provide some insights on this. For example, when we consider a new chemical proposal, it’s because a member state has made the proposal to the COP. COPs happens at intervals of every two years. So sometimes within those two years, a member state might come across information suggesting that a chemical could be harmful. The member state brings forward a proposal to the international arena, usually because they already have domestic legislation related to this chemical. They have this legislation because scientific information emerged several years prior, detailing the adverse effects of these chemicals. So, by the time we include one more POP in the annex of the Stockholm Convention, there have already been years, and sometimes decades, of scientific information available showing the impacts and properties of this chemical. But due to the mechanism of the convention, it wasn’t possible to take action in a timely manner, while the chemical was causing harm on the ground. I imagine that this panel could help in early scanning, identifying potential hazards that we might not be aware of yet in the convention.

There are also cases where we might identify a chemical that, for instance, kills all surrounding wildlife very quickly, but isn’t persistent . However, after lengthy analysis by scientific bodies, it’s considered not to be a POP, and is not recommended to the COP. So then nobody cares anymore because there isn’t anyone or body to continue assessing what happens with this chemical. Even if it’s highly lethal in a localized area but doesn’t persist or travel long distances, it fails outside of the scope of the Stockholm Convention. Looking at the Basel Convention, we provide guidance on best practices for dealing with different kinds of waste streams, but what happens after that? I’m sure there’s a lot of scientific information on the effectiveness of the practices on the ground, how these guidelines are being implemented and how systems are being improved. But currently, there is no mechanism to analyze and evaluate that. Having a scientific panel could help in identifying those effects and could help to improve

I also want to touch on how we engage with stakeholders. It’s not so much about establishing a mechanism as it is to ensure the scientific integrity of the panel. If the panel is producing good outcomes, it will be respected.

The IPCC and the UNFCCC have an institutional relationship, with each one acting as an observer of the other. However, until the Paris Agreement, this relationship was not institutionalized but even before that, every single IPCC report set the agenda for each Conference of the Parties on climate change. On the other hand, we have the example of IPBES, where an institutional relationship is established organically in the treaties with the CBD. Both example work because they are solid panels with robust structures and procedures, making their assessments so solid that they cannot be ignored. This is what I hope for this panel.

Building Linkages from Science to Support Action | Member States’ Perspectives

Francisco Nelson DE ALMEIDA LINHARES JÚNIOR | Deputy Head, Division of Environmental Policy and Sustainability, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brazil

I think the best question that has been raised at this panel so far directly addresses a specific and independent function that we agreed upon in our last OEWG meeting, which is the function of capacity building for the SPP. It wasn’t easy to reach that decision. We are still debating the scope of such function.

When I say ‘we,’ I’m speaking on behalf of my country. We understand the concern of some parties that capacity building could be included in the other functions of the panel, seen as bringing in researchers from the global South to help with the work of the panel. That’s indeed very necessary, but we don’t believe it’s enough. This has everything to do with what our UNEP Deputy Executive Director said when she posed the question: “Where does the SPP role end and how is it translated into work on the ground?”, because for the outcomes of the panel to be truly effective in many countries in the global South, they need to have inputs and insights from local realities. Simply bringing in researchers to work at the panel won’t do that job because the knowledge that will be assessed is not being produced in the global South to the extent that it’s needed. So, we need to help with that.

We understand that the panel should not be doing the work of development agencies. We know that’s not feasible. But how can the panel, how can the function of capacity building contribute to the work of these international organizations dedicated to development? How can we enhance the production of knowledge in the global South that look into their specificities and needs?

Abbas TORABI | Counsellor & Interim Focal Point for Chemicals Conventions, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Islamic Republic of Iran

Nelson gave a very thorough elaboration of the general needs of developing countries in terms of capacity building. I just want to give some examples – of course, this is not an exhaustive list – of the needs of developing countries in terms of capacity building. It’s good to understand the needs of developing countries. Based on that, I believe we can build a beneficial interaction.

- First of all, the lack of a national inventory with regard to chemicals and waste in developing countries is evident, and we see it as a significant challenge for developing parties. Providing scientific information regarding the national inventory of chemicals and waste can contribute to identifying the main challenges and the necessary information to build a database on their national inventory for chemicals.

- The second problem or challenge is technical. One of the most important is the lack of modern and up-to-date chemical laboratories. Without these laboratories, precise analysis of chemicals is not possible, and the results of these laboratories could be used by relevant policymakers in developing countries. The contribution of the Science Policy Panel (SPP) in this regard could be very valuable.

- The third challenge is the lack of common knowledge and awareness in the field of chemicals and waste, both among the public and at the expert level. The Science Policy Panel can assist significantly in this area in developing countries.

- The fourth point is about training. Training experts from developing countries in the field of chemicals and waste. Some of them have good potential and abilities in this field, but as Nelson mentioned, the main strength in this field lies with developed parties. There should be significant interaction between developing and developed countries through the SPP to strengthen the expertise of developing countries in the field of chemicals and waste.

- The fifth challenge for developing countries is the lack of networking at the regional level. Networking could be used for exchange of information and identification of the main root causes of challenges related to chemicals, waste, and pollution. The SPP can also contribute in this area.

- The final challenge is the lack of sufficient investment and financing at the regional level for joint projects in the field of chemicals and waste, and prevention of pollution.

Moleboheng PETLANE | Environment Officer, Ministry of Tourism, Environment and Culture, Lesotho

The relationship between scientific academics and the policy or government official needs to be strengthened such that the research outputs from academics are implemented by the government. Similarly, government should be able to influence the research of academics as determined by policy gaps, countries need to establish academic research forums in order to strengthen their relationship with researchers. We learned over the years that the establishment of national chemicals management committees composed of key stakeholders from all sectors is important in coordinating and strengthening National institutions and strengthening institutional capacities.

Unfortunately, in our region, 75 percent of the work of these committees lack support in research data. Countries in Africa lack data to make informed decisions. We welcomed the UNEA Resolution 5/8 with great enthusiasm as we were hoping for a reform in our policy decision making process. For this to happen, national capacities will have to be strengthened in terms of technical assistance and technology transfer, as Abbas has correctly indicated.

Q&A

Q: How do you see the role of civil society in this process?

Ermira FIDA | IPCC is open to observer organizations, which is a door to all the stakeholders, including civil society, to request accreditation to get a status of observer. The moment that they get that status as observer organizations, they become part of the process of the review of the reports. As I explained in my presentation, the review of the reports is a process that it’s done in ten steps. Part of this ten-step review involves an opportunity for stakeholders involved in the review to provide their comments. Not just necessarily the governments, but also the observer organizations. Here is when Civil Society, once they are engaged with Observer organizations they are attached to, they can be part of the review of the reports. Through that, they can bring in their voice and their opinions about the assessments of the IPPC.

Q: My question is addressed to IPCC and IPBES panelists. From my understanding, whatever you produce is policy relevant but not policy prescriptive. For your self-assessment, did you, through your different assessment, try to understand how useful has been your scientific production to countries, governments?

Anne LARIGAUDERIE | The Secretariat has developed over the years a tool which we call TRACK. We constantly invite all of those that are involved in IPBES or that use the work of IPBES to contribute to that database. Now we have about 500 entries. It includes various ways of use of the work of IPBES, for example statements from G7 or like last week, from G20, a new piece of legislation that very directly cites a key work of an IPBES assessment report. We try, if we learn about it, to document it in our TRACK databases any type of concrete use of our assessment at any scale. We are now covering the globe with all these examples that we have gathered over the years, which really illustrates how IPBES work is being used around the world.

Ermira FIDA | In fact, we undertake assessments, but we don’t call them self-assessments. We go through a process of taking stock of the lessons learned. We are going through the Secretariat of IPCC, which is supporting the IPCC bureau in performing this task. One of the elements that might come in, I cannot share because it’s a draft, is the way that we have performed during the cycle, including in terms of the impact that we are making. It is obvious that the organization is moving towards a status where the findings of the report are not just taken note by the Conference of the Parties, but also by world leaders, heads of agencies, even citizens. At the last Conference of the Parties, we didn’t have this tracking tool, but we have counted more than 10 times the reference to the IPCC findings of the Sixth Assessment Report in the main or overarching document, in addition to the specific decisions made by the parties.

Q: Which scenario or approach would you advise to have a panel that addresses the matters of capacity building, involvement of many stakeholders, and so on? How successful have the existing panels been, and through which means?

Francisco Nelson DE ALMEIDA LINHARES JÚNIOR | I want to touch upon the question on the previous experience of IPCC and IPBES with capacity building. Please correct me if I say anything that it’s not correct. But at the last OWG meeting for the SPP in Bangkok, we had people with experience with both panels. What we learned was that IPCC doesn’t have capacity building explicitly agreed upon under its mandate. And then IPBES, that came after IPCC, made that, let’s say, I like to call it evolution, and has expressed capacity building as one of its functions. It has been doing great work because it tries to bring in researchers from the Global South. It has specific training programs for researchers from developing countries, and that’s very useful. So, the question is, we’re building up a new panel now, can we build upon what’s been done and take the next step? How can we improve capacity building in that sense? So moving to filling in gaps of scientific knowledge production in the Global South. Maybe that won’t be done directly by the panel because it doesn’t have the means to do so, but how can it help other institutions and organizations to fill in those gaps? Because that will bring effectiveness for the outcomes of the future panel.

Carlos MARTIN-NOVELLA | If I see what was discussed in Bangkok, there is a certain convergence from member states that capacity building should be addressed as one of the four key functions of the panel. But this was between brackets, so it remains in some square brackets there. My perception is that the devil is in the detail. So, what is meant by capacity building? If we look at IPBES, it is something very concrete. In the IPCC, there is nothing specific but it’s a scholarship program that could be seen as a sort of capacity building. There are some issues regarding collaboration for the establishment of the Technical Support Units within North and South, aspects that resemble something about capacity building.

Now, I think in the context of the discussions in the Open Working Group, there has to be a bit of discussion on the detail. What is meant by this capacity building? Maybe some aspects can be easily accepted, consensus found, while others can be very difficult. I’m just making a small risk here of potentials, like IPCC-style options. I’m not restricting, just giving options. If you want to promote more scientists in a country in the South, you will need to support the curricula, you will need to have support for the schools. These are activities that lead you in one direction. If what you want is to include more authors in the assessment reports, this is another kind of activities because of different kind of costs. Or, if you want to include more reviewers, if what you want is to have, if there are going to be Technical Support Units or other centralized secretariats, how to incorporate the South in the establishment of these secretariats, in the physical location of the secretariat, especially in the leadership of the secretariats and on the staff. This also has a capacity-building implication.

There are issues related to access to journals. For example, some of the most renowned journals, you have to pay for it. If you have an author from the South, but this author from the South does not have the money for paying for all the subscriptions, then it’s a problem. So, also, the panel could try to address this kind of thing. You could try to involve other organizations in the activities of UNESCO or UNIDO or UNITAR. This whole thing boils down to the detail, and in the detail depends on the topic. It could be a range of solutions, some of them easier, some of them, I guess, more difficult for the member states.

Anne LARIGAUDERIE | Following up on Mr. Nelson’s comments: one of the four functions of IPBES is focused on capacity building. In fact, this was originally a proposal from Brazil when IPBES was being negotiated and has proved to be a successful component of the work program of IPBES. There’s a fellowship program aimed at young scientists from all regions of the world, as well as training programs, tutorials, and special sessions designed to engage developing countries in all parts of IPBES’ work program. The funds that IPBES has are focused at ensuring the work of IPBES engages all regions of the world. Aside from this, there is also a catalyzing effect of IPBES’ work. It relies on a substantial network of other organizations, which, through their capacity-building efforts and with significantly more resources than IPBES, organize their own events to further amplify the work.

Photo Gallery

Documents

Presentations made during the event

Links

- Towards the 2023 Meetings of the Conference of the Parties to the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions

- Ad hoc open-ended working group on a science-policy panel on chemicals, waste and pollution prevention | UNEP

- Road to OEWG 2 | Science-Policy Panel to Contribute Further to the Sound Management of Chemicals and Waste and to Prevent Pollution / SPP-CWP Webinar Series

- Developing a Global Science-Policy Panel on Chemicals, Waste and Pollution Prevention