Événement Virtuel

HRC48 Side Event | The right to science in the context of toxic substances

22 Sep 2021

15:30–17:00

Lieu: Online | Webex

This virtual side-event to the 48th Session of the Human Right Council, is convened by the Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, Marcos Orellana, within the framework of the Geneva Toxic Free Talks, with logistical support of the Geneva Environment Network. The Special Rapporteur will present his annual thematic report to the UN Human Rights Council, dedicated to the human right to science with regard to the risks and harms associated with the life cycle of hazardous substances and wastes, examining the dynamics and interconnections between scientific progress, the diffusion of scientific information and the science-policy interface.

About this Session

Science provides the international community with knowledge about the risks and harms posed by hazardous substances on human health and the environment and thus enables the elaboration of evidence-based policies to address those threats. Science-based policies protect the range of human rights that are compromised when individuals and communities are exposed to hazardous substances and waste. The creation of effective channels connecting science with policymaking is indispensable to advancing the contribution of scientific knowledge to human rights protection.

The right to science implies the availability and accessibility of accurate scientific information to the general public and specific stakeholders. The right to science also requires that governments correct scientific disinformation. It implies an enabling environment where scientific freedoms may be realized and where governments foster needed scientific research on toxic substances that endanger human health and the environment.

The ability of society to benefit from scientific knowledge is threatened by the propagation of disinformation about scientific evidence. The manufacturing of doubt about the risks and harms of hazardous substances by producers of deadly products has become a lucrative business. Certain business entities specialize in deliberately spreading ignorance and confusion in society. Tactics of denial, diversion and distortion are intended to keep hazardous products on the market, despite knowledge of their risks and harms, and at the expense of adequate human rights protections. Scientists themselves are often the target of campaigns that harass, discredit, threaten or undermine them if they question, publish or speak out about the risks and harms of hazardous substances.

The side event will be dedicated to an exchange of views on these and other aspects related to the right to science in the context of toxic substances.

The Special Rapporteur on Toxics and Human Rights

About the Mandate

The mandate on hazardous substances and wastes was first established in 1995 by the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (Commission Resolution 1995/81). Today, it is under UN Human Rights Council Resolution A/HRC/RES/45/17 of 2020.

Learn More About the Mandate and Resolution →

Current Mandate Holder

Marcos A. Orellana was appointed Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights (full title – Special Rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes) in August 2020. He is an expert in international law and the law on human rights and the environment. His practice as legal advisor has included work with United Nations agencies, governments and non-governmental organizations.

Read Marcos A. Orellana’s full biography →

About the Geneva Toxic Free Talks

Geneva Toxic Free Talks

Geneva is a central place for those struggling against the threat of contamination by the use of toxic substances. As the Special Rapporteur reports every Fall to the Human Right Council and to the UN General Assembly on these issues, the Geneva Toxic Free Talks take the momentous opportunity in the year to reflect on the challenges posed by the production, use and dissemination of toxics and on how Geneva contributes to bringing together those working in reversing the toxic tide. This year, the Special Rapporteur will also be presenting a report on Plastics and human rights on 23 September 2021 at 13:30 CEST.

Speakers

By order of intervention.

H.E. Amb. Álvaro MOERZINGER

Permanent Representative of the Eastern Republic of Uruguay to the United Nations Office and other international organizations in Geneva

Felix WERTLI

Head, Global Affairs Section, Swiss Federal Office for the Environment

Marcos ORELLANA

UN Special Rapporteur on Toxics and Human Rights

Laura N. VANDENBERG

Associate Dean of Undergraduate Academic Affairs and Professor, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

Sarojeni RENGAM

Executive Director, Pesticide Action Network Asia Pacific

Monika GAIL MACDEVETTE

Chief, Chemicals and Health Branch, UNEP

Yves LADOR | Moderator

Representative to the United Nations in Geneva for Earthjustice

Summary

Opening Remarks | H.E. Amb. Álvaro MOERZINGER | Permanent Representative of the Eastern Republic of Uruguay to UN Geneva

Yesterday, the UN Secretary General stressed that “science is under assault”. In that sense, we need to take positive action against disinformation, which directly violate the right to science, through global cooperation and solidarity, by disseminating scientific knowledge in a transparent manner and communicating it in plain language, allowing the public to receive the best available scientific evidence, which improves the realization of this right.

Read the full statement of the Ambassador here.

Good afternoon,

Uruguay expresses its gratitude to the Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, Marcos Orellana for timely convening this side event.

I would like to quote the recent UN Secretary General words at the opening of the 76th UN General Assembly “We see the warning signs in every continent and region. Scorching temperatures. Shocking biodiversity loss. Polluted air, water and natural spaces”. In summary, we face three planetary crises: climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution.

Interconnectedness characterizes our time and is reflected in the crisis we face in the XXI Century. These phenomena have multiple ramifications, they require coordinated actions from the States and multiple stakeholders covering different areas, as UN Bodies, civil society, scientists, academy and the private sector. We need to continue working together to address this crisis that know no borders and due to their dimensions, require agile and efficient responses.

In this sense, for better decision-making at the national, regional and international levels, an independent and intergovernmental Science-Policy Panel on Chemicals and Waste should be established. For what purpose? to harmonize, synthesize and evaluate existing scientific knowledge; to facilitate the determination of risks and harmful effects on human health and the environment with a special focus on human rights. International cooperation is of critical importance for developing countries and for the benefit of the international community.

The science-policy panels make a valuable contribution to international negotiations and to the progressive development of international environmental law, which Uruguay promotes since 1981, with the Montevideo Programme for the Development and Periodic Review of Environmental Law. Also, we will be able to strengthening the new framework for SAICM Beyond 2020, the plastic waste management, as well as the global governance of chemicals and waste.

Also, we will be able to accelerate actions to tackle the three current environmental crises at the same time as climate change, protecting biodiversity and preventing and reducing global pollution. We hope to deepen the discussions on the creation of the SPI in the next segment of UNEA-5.

We welcome the report of the Special Rapporteur on “The right to science in the context of toxic substances” that was presented yesterday to the 48° Session of the Human Rights Council, and especially, we would like to highlight the interrelation between the right to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications, referred to as “the right to science” and the right to a safe, clean, healthy and sustainable environment to face the severe toxification of the planet and its people.

He presented a clear picture that the unsound management of chemicals and waste create dangerous sources of pollution for our societies and environment. In fact, most of the global population is exposed to hazardous substances and wastes without their consent, which adversely affect a range of human rights, including the rights to life, health, adequate food and housing, clean air and safe water, a healthy environment and safe and healthy work.

In that sense, several international law instruments as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights recognizes the right of everyone to “share in scientific advancement and its benefits”. Also, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights expands upon this right and the obligation of States.

The right to science is also reflected in regional human rights instruments and several national constitutions. For instance, as recognized by the Special Rapporteur´s report, in the Americas, the inter-American system provides a comprehensive protection of the right to science. The American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, recognizes the right to science in language similar to that of the Universal Declaration. Also, the Charter of the Organization of American States, calls for the sharing of the “benefits of science and technology” among its member States. Lately, the Protocol of San Salvador signed in 1988, further elaborates upon the right to science.

Uruguay legislation recognizes the State´s obligation to prevent the exposure of people to hazardous chemicals and waste and protect them from their risks and harmful effects.

Yesterday, the UN Secretary General stressed that “science is under assault”. In that sense, we need to take positive action against disinformation, which directly violate the right to science, through global cooperation and solidarity, by disseminating scientific knowledge in a transparent manner and communicating it in plain language, allowing the public to receive the best available scientific evidence, which improves the realization of this right.

Likewise, we would like to highlight the importance to protect scientists that are often subject to intimidation, harassment, threats, and persecution, and to promote the exercise of academic and scientific freedoms as well as the right to freedom of expression, which are indispensable for scientific research.

The Special Rapporteur, in the introductory paragraph of his report, expresses: “Science provides the international community with knowledge about the risks and harms posed by hazardous substances on human health and the environment and thus enables the elaboration of evidence- based policies to address those threats. Science-based policies protect the range of human rights that are compromised when individuals and communities are exposed to hazardous substances and waste.”

As an example of the positive link between science and policy, we can describe our response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Uruguayan government has taken decisive actions based on science and on the recommendations of the WHO. Transparent and constant communication, ensuring the population the right to information, public participation and responsible freedom of the population have characterized our management of the crisis.

In this case, all decisions taken were based on the permanent advice of 58 multidisciplinary science experts, members of the Honorary Scientific Advisory Group (GACH) which was created during the health emergency. Several disciplines debated, cooperated and conducted an interdisciplinary dialogue of broad scope. This avoided doubts from the public opinion and allowed to organize successful vaccine campaigns.

Thank you very much

Opening Remarks | Felix WERTLI | Head, Global Affairs Section, Swiss Federal Office for the Environment

Thank you very much for the opportunity to speak today, and for the report. I would like to very much support what His Excellency Moerzinger has mentioned before. I will focus my intervention on the Intergovernmental Science Policy Panel. You might have heard that at the Berlin Conference on Chemicals, earlier this year, Switzerland has made a proposal to take at UNEA5 a decision to establish such an Intergovernmental Science Policy Panel and to launch negotiations for it.

A few thoughts on where we are coming from, what we’re expecting, and also some linkages to the report we have received from the Special Rapporteur. The report highlights the very importance of communication, effective channels connecting science with policy making, and that is exactly what we are aiming to enhance and to improve. At the moment, the Chemicals and Waste Cluster has no international institution such as the climate with the IPCC or biodiversity with IPBES. They have instruments such as the Global Chemicals Outlook, however those are not sufficient. Besides many very important valid information in it, they don’t have the standing and capacity to reach a large audience and to have policy makers be provided the necessary information.

One point we have also seen in the report is that a lot of fragmentation comes in international science policy. I have to admit I’m not fully sure if fragmentation is the right term to describe it, because we have currently very important science policy bodies: for example for the MEAs like POPs for the Stockholm Convention or the Ozone in Montreal Protocol. They have a specific task to fulfill: it is well defined and very important, which makes us think that they work on their own, that they do what they have to do. For sure, there’s always room for improvement. There’s room for adaptation to take up if there’s specific challenges. But in principle they have a clear function.

What we talk about is something else: a science policy panel for the entire Chemicals and Waste Cluster. Switzerland and most probably a few other countries are going to submit together at UNEA 5.2 a resolution suggesting the establishment of such a panel and to launch negotiations. When we talk about a science policy panel, we emphasize that it’s important that it has to be intergovernmental. We need an effective channel connecting academia with policy making and to have the best channel. It is when policymakers can ask questions to academia and academia can respond. It’s a two-way stream because we know in Chemicals and Waste, there is a lot of science and information involved. However, we need to have a way in which policymakers can act on them. This is the best way in our view to achieve this. For example, for climate change, if the policy side can ask questions and get responses that are consensus-based, state-of-the-art, and policy-relevant without being prescriptive. It has to be advice that we can use for policy making. For sure it can’t say how we have to do it. It gives option and then governments have to decide on it.

One part of the report also addresses the question, what is a scientific fact? When we talk about science in the context of the governmental science policy panel then we have kind of a wide meaning. It includes all relevant disciplines, such as chemistry, physics, ecotoxicology, material science, sustainability and economics. So depending on the issue, on what the policies are asking for, we have to get the right scientists, the right academia on board to provide those annual answers.

A very important element is the conflict of interest in policies. Where we have good examples we can build upon their experiences, such as the IPCC’s to work on those issues.

The science policy panel should have three key functions. The first is horizon scanning, the examination of information to identify potential threats, risks, emerging issues and opportunities. It could also be a tool to identify issues of concern and provide evidence-based options on how to address them.

A second function would be undertake assessments on the nature and scale of particular issues. So this assessment of assessments will be basic science, it gathers available information, brings them together, and then answers the questions made by the policy side.

The third would be communications or to provide up-to-date relevant information, catalyze scientific research, have a communication team of scientists and policy makers, and also to present themselves to the public. It’s also the chance to emphasize to better communicate on the huge challenges. As mentioned we have those environmental crisis, we have the climate with IPCC, we have biodiversity where we have IPBES, and now we need one for the Chemicals and Waste Cluster to respond to this one.

For sure we could not make a copy-paste from existing institutions such as the IPCC. We have to find a specific form that is adjusted and adapted to the needs and functions of the chemicals and Waste Cluster. We have to take into account what we have already, such as the Conventions. We have to address, to find and to access the knowledge that exists. In particular, we have to include the IOMCs and UN organizations that work on chemical safety, design measures of chemicals and waste. As it goes it shouldn’t only be about the environment, it has to be about environment and health, so we have to very strongly include UNEP and WHO. To fulfill the list also we have to find a way to work with our stakeholders, non-governmental organizations, private sector and so on, to harness from their experience and their knowledge to have really fulfilled the sound information.

Thanks again for the opportunity to be part of this panel today and for the report. As mentioned it was quite a good food for thought. You have highlighted some important challenges. You’ve also raised the opportunities and what we see as a key opportunity is to establish such a panel to take up important questions to deliver sound information and policy relevant options to improve the sound management of chemicals and waste. Thank you.

Presentation of the Report to the Human Rights Council | Marcos ORELLANA | UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights

Thank you very, and thank you also to Uruguay and Switzerland for co-sponsoring this event, as well as Earthjustice, Center for International Environment Law, and the Geneva Environment Network.

I am very pleased to be with you today, and to speak about the report that I presented yesterday to the Council on the Right to Science and its implications for the sound management of hazardous substances. By way of introduction, I could start by saying as I mentioned yesterday that the Right to Science has largely until recently been ignored by the human rights community, and it’s high time for it to be given the role and implementation that it deserves.

In that regard, General Comment 25 of the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights that was produced last year in 2020 provides already a solid basis to explore the implications of the Right to Science in the in the toxics context. These implications must take cognizance at the outset of at least two elements of reality that I wish to highlight the first one as already mentioned by His Excellency Ambassador of Uruguay, and quoting Secretary General also the High Commissioner’s opening statement to the Council a few days ago, talked about the triple crisis of pollution, climate change, and loss of nature that is affecting humanity. In the face of this crisis, we need all the tools that we can muster in order to confront it and overcome it. That’s the first very big point.

The second one is the attacks against science either for profit or ideology. We have seen over the last years and decades a concerted attack against science and scientists. Whether it’s disinformation for profit or ideology, whether it’s attacks against scientists for other reasons the outcome of that is confusion, and that is to the benefit of those who want to continue to profit from the status quo. The report puts an emphasis on the science policy interface which is also guided by the most recent Human Rights Council resolution that we knew puts an emphasis on this element.

The report describes science. It describes what is scientific evidence then provides an overview of how the right to science is recognized in global and regional human rights instruments. It identifies threats against science and scientists. It also identifies mechanisms for science to inform toxics. I will speak to these elements in a moment but I also wish to highlight what the report does not cover. This is not the first report of a Special Rapporteur on the Right to Science. There have been previous reports that focused on intellectual property rights, for example, so I do not get into that. I do also not get into the question of how science or its applications and themselves violate human rights.

So in terms of what is sciene only a couple key points to highlight. Science is a body of specialized and specific knowledge, of knowledge accumulated through an iterative, logical and empirically-based process. I emphasize this because this body of knowledge can be distinguished from other forms of knowledge such as experiential knowledge of local communities that may be affected by chemicals and waste, or traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples. Now this distinction has a couple implications: one is on the participation in the process of science. So there, the report speaks for example to so-called citizen science and the importance of protocols and the information derived from that experience. This is an element also that ties with agency in that communities, where with the information, they are able to take their destiny in their own hands and be the best advocates for their interests. Then there’s participation in decision making, or how the decisions flow from the scientific process. This is where the right to science connects quite directly with the right to participate in the decision-making and right to information as well. That’s another element that I wish to highlight: science as a specific form of knowledge.

A second element is that science involves an enabling environment for scientific evidence to flourish. What are some of the elements that go into this enabling environment? The freedoms to determine topics of research, whether it’s basic science or applied science. Perhaps a counterpart to that freedom is the government’s duty to also make sure that there are resources available for research on issues of particular social need. So not only the interests of some segments of the population, especially wealthy components that can afford certain technologies but also what does the right to science mean for the prevention of exposure to hazardous substances. Another freedom that is central to enabling environment is the freedom to act from undue pressure. This links to a freedom of expression and information which is so often curtailed, and I’ll come back to this when talking about threats to science and to scientists.

The second big component in the anatomy of the report is the analysis of international instruments. It goes into looking at the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as well as the Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights; the way that the Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights has interpreted the totality of Article 15, not just the element that focuses on the right to benefit from scientific progress and applications but a point that i wish to highlight is that even those regional systems that do not explicitly recognize a standalone Right to Science have nevertheless in their jurisprudence, in hearing cases, elaborated on the significance of scientific evidence. For example in the jurisdictions of the European Court of Human Rights, in relation to Article Six on fair trial latency periods and the denial of justice in exposure of toxics, Articles Two and Eight on privacy and private life, the right to life in relation to environmental risks jurisprudence takes account and builds on issues of environmental risks and environmental evidence. Similarly with the African Commission on Human People’s Rights where the right to a healthy and safe environment has been interpreted in relation to scientific evidence and the participation of communities in decision making.

On normative content, what does the Right to Science actually require? How can science be used and should it be used to inform policy? The starting point here is to recognize that one of the key benefits of science is the generation of scientific knowledge. But that scientific knowledge will not benefit society unless it is translated into actual measures that provide protection to the population in relation to the risks and harms that scientific evidence reveals or uncovers. That’s where the science policy interface becomes so important.

Now in order to operationalize that unpacking several duties is first of all the availability and accessibility of scientific information. This includes the underlying data on legislative proposals. For example, the availability of scientific evidence enables the taking of measures on that basis and that can be regarded as the duty to take measures and some positivity to align the existing regulations with best available scientific evidence. This brings in a dynamic concept of, for example environmental and health regulations, as science progresses so it is expected that regulations will also progress.

One point I wish to highlight here it also came up in the interactive dialogue yesterday is the best available scientific evidence is not a monolithic body of knowledge. At times scientific evidence close to a core of consensus may show precisely that level of consensus, of what is a fact but moving out of that. Or there may be divergent or minority views. Now so long as the knowledge is derived from scientific method that it follows peer review, that there’s ample opportunity for expression opinion for testing interrogating, that there’s transparency, etcetera, the components of what makes an enabling environment for the scientific undertaking, those divergent minority opinions can very well form the basis of policy. The WTO for example in its jurisprudence has recognized at least that much.

Another point that’s worth highlighting here is on the precautionary principle. This was also a question yesterday in the interactive dialogue because it is at times argued that the precautionary principle is anti-science. It would justify measures without scientific evidence and that’s a complete distortion of what the precautionary principle’s function and role is about. The precautionary principle begins to fill gaps and complements scientific process. Scientific processes by its own nature are inherently an interrogation, a constant process of interrogation and review. The knowledge is incremental. There may well be gaps and there are unavoidable uncertainties and so in order to take measures and frame policies in those situations and circumstances, the precautionary principle plays that role. It has been understood as an element of due diligence by recent decisions of international courts that have looked at this. For example the Interamerican Court’s advisory opinion on human rights and the environment a couple years ago, and similarly the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea. It has been critically important for decisions at a national level.

To another key element of normative content which is international cooperation. International cooperation is critical as the pandemia has shown. Solidarity is one of the critical elements that are needed in order to overcome this global threat. Now it can take place bilaterally, but developing countries often lack the resources and capacity to conduct original scientific research and very well can benefit from the information that is derived in other parts of the world, and not just bilateral cooperation, information clearing houses, among others but also globally or internationally. That’s where science policy interface platforms play a very important role. The report scans the landscape of existing platforms, particularly on Multinational Environmental Agreements and concludes that they’re fragmented. I take the point just made by Felix from Switzerland that fragmented may not be the most felicitous expression. What’s intended here is that the scope of meas is focused it’s limited, and so the science policy interface serving that MEA is necessarily so also limited. So we have kind of an archipelago of platforms. In that sense they’re fragmented.

In some other senses they’re limited in that at times the evidence so derived and assessed in those platforms has not translated into actual measures of protection. The example of the Rotterdam Convention in regards to asbestos or paraquat is ostensible, and steps to overcome that paralysis is very important. So to echo again Felix Wertli, the need for a global platform, as he said horizon scanning — not just on the terms of reference of one MEA but on the whole field, of what’s coming up in the horizon, authoritative assessments and and he also spoke about communication, but perhaps i would frame and nuance it as awareness in the public. There’s an element of education.

So very quickly then passing to talk about a few of the threats that the report identifies against science and against scientists. The tactics to divert and delay: some of the playbook here often deployed by industry was developed in the 1950s, originally by the tobacco industry. This has since been applied in a range of areas (climate change, chemicals, etc.) to highlight alternative explanations and divert attention, or to claim lack of proof and demand ever increasing scientific evidence so paralysis by analysis, or funding front groups that appear legitimate to appear as devoted to the public interest but are really there to confuse, and thus producing uncertainty and disinformation. This, in this way, is a direct attack against the Right to Science.

Another point worth highlighting here is conflicts of interests. Conflicts of interest, inappropriate financial relations between those scientists other persons involved in the science policy platforms can undermine the whole effort of translating science into policy. There is a big debate as to whether conflicts of interest should be managed or should be avoided altogether. Managed as in disclosures of affiliations are avoided as in clear terms of reference for who can sit in or who is not welcome to sell these platforms. The report takes a very clear position that conflicts of interest should be avoided in order to preserve the credibility of the scientific enterprise. There’s more that could be said about greenwashing, or the appearance of efforts while nothing changes or “woke-washing”, so blaming the poor for not taking measures that could affect the poor. This is big in climate change as well but those are a few of the threats that are directed against science. The threats against scientists campaigns of harassment intimidation against them and their families this is all very worrying. One point that the report makes is that scientists who sound the alarm on risks and harms associated with hazardous substances should be regarded and protected as human rights defenders and benefit from international national instruments for their protection, including whistleblowing protections.

To conclude very quickly the Right to Science is a key tool for humanity to confront the triple crisis of pollution climate change and biodiversity. For this it requires that measures be aligned with the best available science. In order to achieve that, science policy interface platforms that are free of conflict of interest are key and critical to transform knowledge into policy.

Thank you very much for your attention and I very much look forward to any comments and questions that you may have. Thank you.

Disinformation campaigns through distortion of scientific information and dissemination of fake science, silencing of scientists and means to combat such practices | Laura N. VANDENBERG | Associate Dean of Undergraduate Academic Affairs and Professor, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

I appreciate the opportunity to be here and to contribute with comments on the issues related to why providing people with information, scientific knowledge is a human right. My work has focused on two aspects of this question.

One is as a laboratory scientist, a research scientist, I and the folks that work in my lab have worked hard to evaluate the effects of numerous chemicals on health effects using laboratory animals. My work has contributed a lot of knowledge specifically on a class of chemicals that are known as endocrine disrupting chemicals or EDCs. There has been a lot of work that’s been done at the United Nations, at the WHO and in international organizations that focused on identifying why EDCs pose such a hazard to the public. These are chemicals that pose threats because they’re hazardous to individuals and to communities. They’re hazardous to workers who are exposed during the production of the chemicals themselves or products. And they’re also hazardous because many of these chemicals persist in the environment and continue to affect populations, long after their use was ever intended. They in fact they affect more than just human populations but also wildlife populations.

More recently my work has also started to focus on understanding why the best evidence is not actually used by regulatory agencies or governments to protect public health. One of the reasons why is that there’s a there’s a large concerted effort by polluting industries and manufacturing industries to continue to promote the use of chemicals, even after those industries themselves have knowledge of the harm that those chemicals can pose.

This is not news to anyone who’s been around for the last 50 years and saw many tactics that were used by the tobacco industry to try to promote the health of tobacco in some cases, or to refute really solid scientific knowledge that’s not refutable about the effects of tobacco on human health. The tobacco industry provided us with what they referred to themselves as a playbook. In Industry documents that were released after lawsuits against the tobacco industry, the tobacco industry acknowledged that their goal was not to um sell tobacco alone but also to convince the public that there was insufficient evidence of harm associated with tobacco.

Work that myself and my colleagues have been doing for the last several years is intended to understand these tactics that were developed by the tobacco industry, and that now we see widely used by other industries. Several experts have referred to these tactics that collectively are used as ways to manufacture doubt. We define this as actions that deliberately alter and misrepresent noble facts. These aren’t areas where there’s honest scientific debate, but where there’s knowable information that individuals deliberately alter or misrepresent to promote an agenda often to benefit a broader industry, a specific corporation, or a group of individuals. This last point is very important. It is where we separate those who manufacture doubt from those who perpetuate doubt.

The average person who is sharing a meme on facebook or tweeting a tweet that is outside of their area of expertise, may be doing something that benefits industry, but without the knowledge that they’re doing it for that reason. We refer to those as doubt perpetuators. In fact, the use of social media and the spread of information in more modern ways has allowed doubt to be perpetuated in lay audiences in ways that it was not in previous generations.

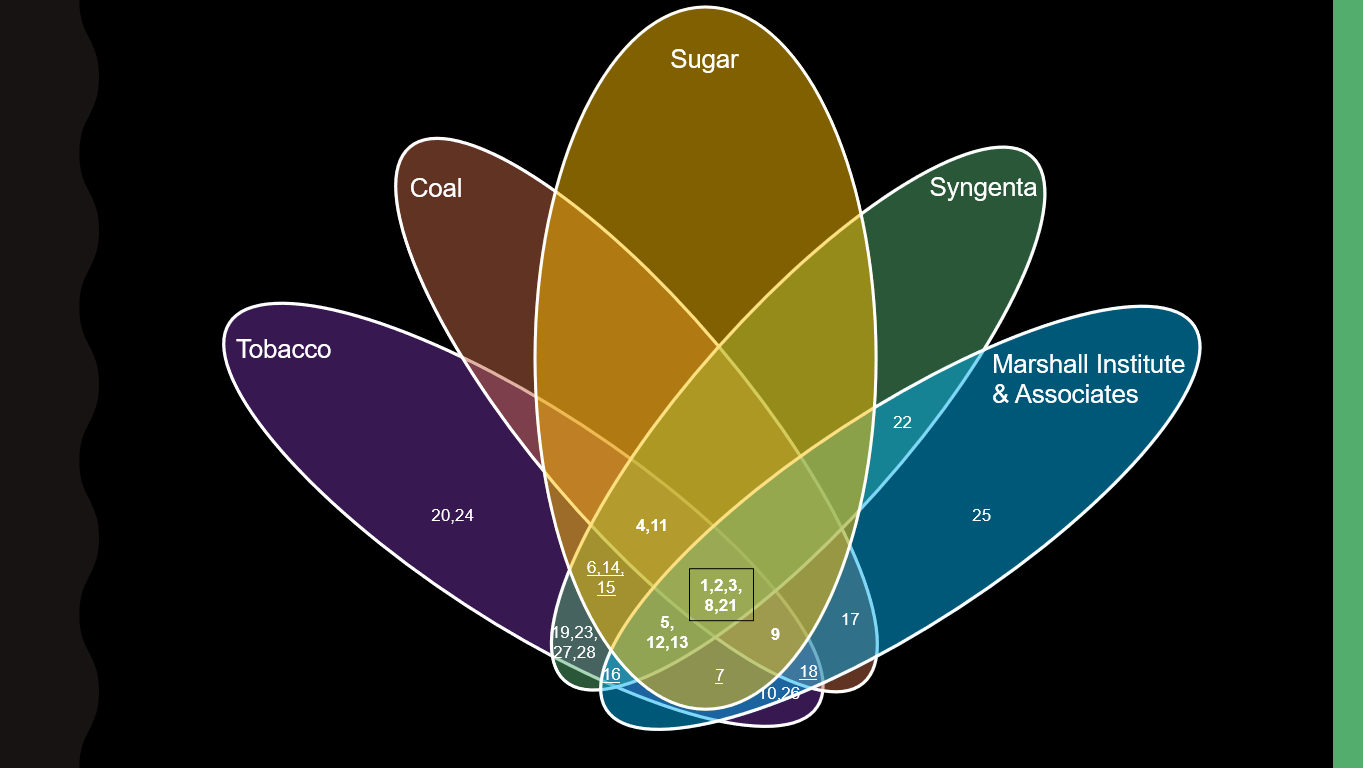

One of the things that we have been doing is to look across industries and try to understand the various tactics that been that have been used across different industries. My colleagues and I selected case studies that are exceptionally well documented. We can get primary documents from these various industries from individuals that were involved in these cases, and we compared them to see where is their consistency and the kinds of tactics that are used by industries to manipulate knowledge and to manufacture doubt. The five industries that we have looked at to date include some that are really large industries like tobacco or the sugar industry, others that are much smaller so focused on a single chemical, in this case the production of atrazine, which is a pesticide used to control weeds, and also things that don’t just involve a single industry but multiple organizations, like discussions around climate change. What we did is to evaluate as many documents as we could from those five industries. We identified 28 unique tactics that are used by one or more of these industries to manufacture doubt.

- Attack study design

- Gain support from reputable individuals

- Misrepresent data

- Suppress incriminating information

- Contribute misleading literature

- Host conferences/seminars

- Avoid/Abuse peer review

- Employ hyperbolic language

- Blame other causes

- Invoke liberties/censorship/overregulation

- Define how to measure outcome/exposure

- Take advantage of scientific illiteracy

- Pose as defenders of health/truth

- Obscure involvement

- Develop a PR strategy

- Appeal to mass media

- Take advantage of a victim’s lack of money/influence

- Normalization

- Impede government regulation

- Alter product to seem healthier

- Influence government/laws

- Attack opponents

- Appeal to emotion

- Inappropriately question causality

- Make strawman arguments

- Abuse credentials

- Abuse data access requests

- Make slippery slope arguments

There’s a range of tactics that are used. These target different audiences. In some cases, the point is to try to convince the public that there’s nothing to worry about, in other cases the point is to try to convince the judicial system or regulatory systems, sometimes it’s to try to influence other scientists and experts in the field. Different tactics are better employed depending on who is the intended audience of that manipulated information. Of these 28 tactics several were shared by all five of the industries that we examined, which means that these are incredibly effective tactics that are used broadly to try to manipulate public knowledge and to manipulate decision making around obvious public health threats.

Other tactics were unique to specific industries because the tactic was designed to protect some aspect of that industry’s behavior. These are the tactics that are widely shared across industries and are quite effective:

- Attack the scientific studies: this is not to say that there is such thing as a perfect study. There is no such thing as a perfect study. Every study has flaws or limitations to it. When using this tactic what industries do, is they take science and they tear it apart. They emphasize study designs that really would only have a minimal impact on the outcome. And they emphasize flaws in studies that are often some of the best evidence that the polluting industry is causing harm to the public.

- Gain support from reputable individuals: they’ll look for politicians, members of industry, doctors, scientists, health officials, to try to defend the product. In some cases, these are experts who would have a reasonable reputation that’s involved in the field. So finding a doctor to talk about an effect on the liver makes sense, finding a physicist to talk about an effect on the liver doesn’t make sense, and yet you can find physicists who will speak outside of their zone of expertise and will use their credentials to support unsupportable cases.

- Use misrepresent data: there’s a bunch of ways that this can be done. Industry can design studies purposefully to fail and then use them to pollute the scientific literature to suggest that there is doubt when no doubt actually exists. There are plenty of ways we all know to cherry pick data to support one viewpoint versus another. Oftentimes when this is done, the cherry-picked data also have other conflicts of interest, so there’s other reasons to not support using those data.

- Use of hyperbolic language: we’ve seen this a lot with climate change, we’ve seen this a lot with studies of agrochemicals. This use of buzzwords like junk science versus sound science is a really easy way to dismiss entire fields of study. I’ve seen this done with environmental epidemiology, to suggest that an entire field of study should not be trusted. The public has a very hard time understanding the nuances of various scientific fields and they can fall victim very easily to these kinds of labels of junk science or sound science.

- Use power and proximity to regulatory bodies to influence government action or change laws in ways that are pro-industry: an example of this that we saw in the United States, were laws that were meant to protect companies involved in coal mining, to actually be able to legally define medical thing, like what is black lung, or what criteria have to be met to be considered a case with black lung.

There are series of other tactics that have been identified that were used by multiple industries but not all of them, which suggests that they’re highly effective, but maybe not essential tactics. These include tactics where:

- industries actively suppress information that they have access to that would be incriminating.

- industries are involved in determining how to measure an outcome or an exposure. Again, the exact example of black lung would be um a great example of this. With biomonitoring, if a chemical isn’t found at a certain concentration, we determine if that concentration is hazardous or not hazardous. It doesn’t matter what scientific consensus actually says about that.

- Industries contribute misleading literature: they take advantage of the fact that non-scientists often lack scientific literacy or are entirely scientifically illiterate.

- they pose as a defender of health or truth. We already heard about that this today, that the ability to sort of create front groups that pretend that they have the public’s best interest in mind, but really their goal is to manipulate knowledge and to manufacture doubt about the harms that come from chemicals. We see this widely in my field of study.

- the ability to blame other causes.

There’s a lot of appealing to emotion that we see. The suggestion that regulations will cause people to lose their jobs, to lose their ability to farm that will lose our ability to feed people. Those are arguments that are not often grounded in any science at all and are used to appeal to emotion.

One of the best things that we can do to combat the use of manufactured doubt is to teach people, including decision maker, because we are all prone to falling victim to logical fallacies. In fact, there are studies that show that scientists are often no better than the average member of public at identifying logical fallacies, because we’re prone to falling for them. We have to find ways to educate people, and this means educating our colleagues as scientists, but also educating decision makers so that everyone at all levels of public health promotion can recognize when doubt is being manufactured and combat it so that we can prevent the harm that pollution, that climate change, that other very serious public health harm could bring to people can be fought with competing logic.

Citizen science, practical application of the right to science to the benefit of communities | Sarojeni RENGAM | Executive Director at Pesticide Action Network Asia Pacific

Thank you, Yves, and thank you for the invitation to the side event. Thank you also for the excellent report of the Special Rapporteur on Toxics.

My topic is Citizens Science, and we actually have developed what we call a community-based pesticide action monitoring. These are some of the photos from that monitoring and the one highlighted in the middle is this paraquat (a toxic chemical used as a herbicide) we found being sold in plastic bags. It was about three years ago in India, and it’s not just in India but it’s all over. This is the kind of documentation that groups on the ground at the community level are documenting and bringing up for policy changes at the Rotterdam Convention to show that paraquat is a dangerous pesticide and that action needs to be taken.

In 2017, the human rights experts call highly hazardous pesticides a global human rights concern because of the catastrophic impact on the environment, human health, and society as a whole. It was a joint report from the Special Rapporteurs on the Right to Food and Toxics.

So why did we start this process of you know community monitoring? One of the key things was that we were very concerned about the impact both in terms of environment and health of pesticides. There was very little information of the reality of pesticide use in communities and on the ground there was a big information gap. We also thought we need to have the community involved to be empowered, to take action based on the kind of documentation of the harm that is caused by pesticides but also the way that it’s being used at the local level.

In 2020, there was a report that showed that there’s an estimated 385 million cases of unintentional acute pesticide poisoning every year, which are mainly occupational including 11,000 deaths. You’re talking about 44 of all farmers and farm workers and mostly from the south and that’s a big concern. This CPAM tool was important to make sure that we have the documentation, that we have the community engaged in this so that they can take action at the community level as well as at the policy level. This is how we envisioned this would work we talked about. We always discuss with the communities through the partner organizations at the national community level. It’s community empowerment, using available knowledge and tools to document what’s happening on the ground. Increasing the level of scientific and technical competence at all levels. We train farmers and workers and women gather that information working with the CSOs on the ground. Of course, there’s big collaboration between the community, health groups, health workers, NGOs, CSOs, scientists, public health experts, etc. This documentation becomes very important not only to assist in organizing and mobilizing farmers at the community level but also reaching out to others who are being affected by these pesticides and feeding that into policy both in terms of local government and at the national level through campaigns, policy discussions, as well as to promote alternatives or agroecology alternatives to hazardous pesticides.

Through this documentation, we are feeding it also at the international level so it’s basically what is CPAM a systematic method of participatory action documentation on the impact of pesticides. It’s done by farmers and agricultural workers and by the communities with the support of the CSOs. It’s for action.

Moving on, these are some steps in CPAM. Training our facilitators on the use and conduct of CPAM, analyzing and developing the report together with the community so that we can always validate and the information goes back to the community, then follow-up and action as mentioned earlier.

This was one of the results of CPAM at the regional level but we have lots of national reports. This was done for two years. A thousand farmers and workers were interviewed and became part of the CPAM process. These are some of the findings that we found. Through that monitoring we were also able to identify some of the highly hazardous pesticides where the community then can take action to start campaigning and demonstrating public protests as well to create awareness at the community and national level. I just want to show how the the documentation looks like. What is interesting for us was that seven out of the ten interviewed suffered symptoms of pesticide poisoning. This goal is actually quite similar to the monitoring that FAO was doing in the Mekong countries. They also found seven out of ten farmers and workers interviewed suffered symptoms of pesticide poisoning.

Some of the successes we have found was due to the support from the community, the local CSOs that we were able to work with, as well as some of the government officials. We have banned pesticides in Vietnam, Malaysia, India and Sri Lanka. In fact, Sri Lanka got the World Future Council award because of the tremendous work they have done to reduce the risks of pesticides in the country. It was a long struggle and it took years. I really feel for what Laura was saying because that’s exactly what happened in all the cases, where we were able to bring CPAM documentation with secondary data in scientific studies to show that this particular pesticide is a problem. For example paraquat, it took so many years to get it banned in Malaysia. The documentation helped communities to identify the problems, the pesticides and to take action. What is foremost very important was the community getting organized because they see what’s happening, where they get to say, “This should not be affecting us and our families nd we should work together and organize ourselves to take action.”

One of the other key elements of this was that while they were doing these campaigns they also say what the alternatives are, and how can we get out of this cycle of poison. That’s when they start to talk about exploring (alternatives) with other farmers, in terms of agroecology or organic farming and practices. Awareness building is for us another critical element. This is a five-year-old son of an activist who said, “I love organic food.” He was five and we took a photo of what he felt: that he wants organic food.

I wanted to share two cases case studies. One, where we were in Sri Lanka we started to work with a group of women. They started CPA monitoring and then they found, when the farmers were getting sick and suffering the adverse effects and they said let’s organize. Let’s mobilize women farmers to confront these pesticides. They identified paraquat then they had a big campaign. Sri Lanka finally banned it. This was you know a decade ago and they started to strengthen their perspective and expose the corporate control of the trade of these chemicals. They also started to organize themselves as a company, as a national federation. After three decades they have succeeded. In a big way there lots of women farmers and workers who are practicing agroecology. You have Sri Lanka as very progressive in terms of bans of pesticides compared with other countries in Asia. They’ve continued to advance their struggle for land for women farmers, so it went beyond pesticide issue to also take on issues on the ground that was so important for women farmers.

Then another case study was more recent. This happened in Yavatmal in india in 2017. Over 80 farmers were poisoned and died. In fact when the government investigation did the investigation, they found 272 farmers have died due to pesticide poisoning in four years in that area. Together with PAN-India Panel, Public Eye, and another German group, we we did the documentation and we found that Polo or Diafentiuron was used. Some farmers linked it to their poisoning and so now the documentation was compiled and brought to the OECD. Through their complaint mechanism 51 victims have been identified suffering ill effects of Polo and this is in a kind of process right now. Furthermore, we had an additional three victims using uh Polo who said that they were incapacitated and they have filed legal suits. One passed away and so his wife is part of this legal suit. PAN-India has demanded Syngenta to stop selling brands like Polo. In India, because farmers cannot do not have any access to PPE, and it’s impossible in a climate like India. Of course polo is banned in Switzerland where the company is based but what’s also very important is that the community has organized itself. It’s gone to do national policy advocacy campaigning and they are called the Maharashtra Association of Pesticide Poisoned Persons (MAPPP). That is a way that they can continue the struggle even when some of the cases don’t [move forward] because it will take a long time for the legal case, etc.

In conclusion, I just wanted to emphasize that citizen science or CPAM is really for us a way to meet the needs of communities and contribute to the relevance of science so it adds to the level of scientific knowledge but as well as a tool that could use that we could use for campaign and advocacy. It provides the underpinning and supports the Right to Science at the community level. That’s why we find this document and the report of the Special Rapporteur very important: it helps to strengthen community organizing around impacts of pesticides and chemicals on health and the environment.

This is a photo from Vietnam where they’re taking action. They’re saying these are the impacts of pesticides and we need to do something about this. It also empowers farmers to make the shift from pesticides dependency to agroecology, and we know thousands of farmers in Asia uh and elsewhere are showing agroecology works and is economically feasible.

Thank you very much for this opportunity.

Relevance to UNEA and ICCM5 process | Monika GAIL MACDEVETTE | Chief, Chemicals and Health Branch, UNEP

Thank you very much. I just would like to take these last few minutes of the webinar and perhaps recap and reiterate and reinforce some of the things that have already been said and mentioned about the need for a science policy interface, but from UNEP’s perspective.

What I’d like to do is bring to your attention that the work that UNEP did on the Science-Policy Interface recommendations was a mandate from the UNEA, so the member states asked UNEP to do this. This builds on the recommendations that came out of the Global Chemicals Outlook 2 to strengthen the Science-Policy Interface because some of you may recall that the 2nd edition found that progress had been made but much more needs to be done. So UNEP was called upon to come up with some options on a Science-Policy Interface. There’s the language that was used to give us our marching orders.

So just to recap what was in the report. The report reviewed of a variety of existing Science-Policy Interface platforms and models and discusses some of the lessons learned from these. In terms of looking at some of the impacts and the outputs of a strengthened science-policy platform, how such platforms can inform different stages of the policy making process, some of the key characteristics of science policy interfaces, noting that they are rarely linear and are more accurately represented as several iterative phases that feed into and shape one another. So what we need to keep in mind — I think this was really borne out in some of the previous presentations, and the need for unbiased and a sort of scientific fact presentation — is that a science policy interface that seeks to facilitate and inform discussions on how to strengthen the science policy dialogue for, in this case in particular, chemicals and waste management. Thus supporting and promoting science-based local, national regional and global action on the sound management of chemicals and waste. We’ve seen some really amazing and very powerful examples from the local level also to the global action level.

The science policy interfaces also aims to provide elements for bringing agendas together and how science policy platforms need to interact with and inform each other. We did hear of some of the examples of the IPCC for example and the IPBES for biodiversity and ecosystem services. Very key to looking at science policy interface are the ability to support national agencies and other groups; with, as was rightly pointed out by by Marcos, awareness raising activities, also building capacity; access to and development of information to prepare policy through tools and other methodologies; and also the ability to implement actions related to the sound management of chemicals and waste. So there are a lot of really good reasons why we should be moving in this directio.

I just want to acknowledge in this particular slide the very generous, both financial and moral support from the government of Switzerland but also the University of Massachusetts, and I suppose in some ways the father of a lot of the science policy interfaces, Sir Bob Watson and the real support that was given by John Roberts. This was also done in consultation with the inter-organization program for the sound management of chemicals or the IOMC, and also the Multilateral Environmental Agreements and their Seecretariats.

So as has been mentioned in the past, some of the key sort of characteristics of science policy platforms are sort of articulated on this particular slide here and they need to be considered together. I think we have already heard the need for science policy interfaces to be able to engage in horizon scanning, looking into the future to identify emerging issues of concern, monitor the trends that are happening; identify, assess, and communicate environmental and human health issues associated with, in this case again, chemicals and waste; evaluate and refine response options, practices, policies and technologies; and potentially stimulate the negotiation and enactment of new policy approaches. As we’ve found out from our previous speakers, you can really only gain a lot of success and be authoritative when you’re credible, relevant, legitimate and transparent and so these are the hallmarks of science policy interfaces that really do need to to be captured.

What I’d like to do is just conclude that by the findings in this report, it really did look at the landscape of existing science policy platforms and it did conclude that what is currently out there is not comprehensive enough to address the multiple facets of the sound management of chemicals and waste. There’s fragmentation, isolated approaches and perhaps even siloed approaches that are not overall and overarching and comprehensive but sometimes even in an ad hoc manner. So the current models do not really allow for informed decision making or actions at the national or international level in a comprehensive manner. Akin to the IPCC for climate change and the IPBES for biodiversity and ecosystem services, the call for something of an equal footing for the sound management of chemicals and waste really is timeous.

I’m going to end there and perhaps leave just a few minutes for questions. It’s been a very rich and very full session and I hope this has helped to sort of wrap up some of the things that has been said. As always UNEP stands ready to support its member states and stakeholders in the directions that we want to take the world. Thank you very much.

Closing

Considering that there are only a couple minutes left, I will undertake to answer any questions by email to any of the participants, and only at this time, thank my fellow panelists for their insightful presentations.

The report on the Right to Science in the toxics context provides analysis, a diagnosis that elaborates on what are the tools that are offered by the Right to Science to overcome the detoxification of the planet that we’re facing. It gets into questions of normative content. It analyzes some of the tactics used with impunity. This is a point that I want to stress because in order for the report to be meaningful, it has diagnosis but it also needs to be translated into actual solutions.

The report has several recommendations that I hope are viable and measurable and can be implemented. Much of it comes down to meaningful public participation, access to information but also back to the issue of impunity, actual sanctions, actual measures adopted by states to combat misinformation. There are sanctions for lying in the securities market, in the free competition act: there’s fraud. But what about lying when it comes to uh the formation of regulation and the toxics and waste field? There’s much to be done there so with that all antennas tuned to the next 5.2 session of the UN Environment Assembly where we may see good progress on a global science policy interface platform as discussed in the panel.

I invite you the audience to use the report. I thank you very much for your attention and I thank also all the co-conveners. Thank you.

Video

In addition to the live WebEx and Facebook transmissions, the video is available on this webpage.

Documents

- Invitation

- The right to science in the context of toxic substances | Special Rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes | A/HRC/48/61

- Presentations

Links

- 48th session of the UN Human Rights Council

- Environment @ 48th Session of the UN Human Rights Council

- Developing a Global Science-Policy Body on Chemicals and Waste

- Human Rights and Hazardous Substances | UNEP and OHCHR

- Toxics exposure: ‘Follow the science’ to protect lives – UN expert | SR Toxics | 21 September 2021

- Chemicals and Waste | From Science to Policy, Global Issues of Concern, Challenges and Opportunities | GENeva UNEA Briefing | 20 October 2020

- UNEP Report | Assessment of options for strengthening the science-policy interface at the international level for the sound management of chemicals and waste

- UN expert slams chemical industries for spreading fake news about risks | Michelle Langrand | Geneva Solutions | 22 September 2021