Événement Virtuel

Plastic Chemical Threats to Children’s Health & Development: Opportunities to Protect Children’s Health and their Future in the Plastics Treaty

16 Avr 2024

15:00–16:30

Lieu: Online | Webex

Organisation: International Pollutants Elimination Network, Geneva Environment Network

This event is co-organized with IPEN, within the framework of the Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues. Leading experts at this session will discuss opportunities to protect children’s health and their future in the Plastics Treaty. Interpretation provided to Spanish and French.

About this Session

Many harmful chemicals are used during the production of plastics, either as building blocks of the plastic material itself or as additives to provide certain properties such as color or flexibility. Hazardous chemicals may also be present in plastics from contamination during production, such as styrene monomers, or formed during recycling, such as dioxins. These chemicals can leach into food, water, and the environment.

Microplastics are widespread contaminants of the environment today that both contain hazardous chemicals as part of the material but that can also adsorb, magnify, and spread environmental contaminants such as PCBs. Hazardous chemicals in plastics are a source of concern because many of the chemicals that leach from plastics are EDCs. These EDCs include bisphenols, alkylphenol ethoxylates, perfluorinated compounds, brominated flame retardants, phthalates, UV stabilizer, and metals. The leaching of these EDCs from plastics is of concern because they have been shown to cause abnormal reproductive, metabolic, thyroid, immune, and neurological function. This has led to numerous international scientific societies such as the Endocrine Society and health organizations to weigh in and it has contributed to science-based action on EDCs by many stakeholders including some governments, retailers, and manufacturers. However, more efforts are needed to protect people and the environment from potentially harmful EDCs in plastics.

Leading scientists from the Endocrine Society and the TENDR collective, joining the panel of this event, will present the latest science illustrating the impacts on children’s hormones and neurological systems from plastic chemicals. This event, taking place ahead of the fourth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment (INC-4), aims to provide a compelling argument for the protection of human health in the global plastics treaty.

Interpretation was provided to Spanish and French.

Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues

The world is facing a plastic crisis, the status quo is not an option. Plastic pollution is a serious issue of global concern which requires an urgent and international response involving all relevant actors at different levels. Many initiatives, projects and governance responses and options have been developed to tackle this major environmental problem, but we are still unable to cope with the amount of plastic we generate. In addition, there is a lack of coordination which can better lead to a more effective and efficient response.

Various actors in Geneva are engaged in rethinking the way we manufacture, use, trade and manage plastics. The Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues aim at outreaching and creating synergies among these actors, highlighting efforts made by intergovernmental organizations, governments, businesses, the scientific community, civil society and individuals in the hope of informing and creating synergies and coordinated actions. The dialogues highlight what the different stakeholders in Geneva and beyond have achieved at all levels, and present the latest research and governance options.

Following the landmark resolution adopted at UNEA-5 to end plastic pollution and building on the outcomes of the first two series, the third series of dialogues will encourage increased engagement of the Geneva community with future negotiations on the matter.

Speakers

By order of intervention.

Serge Molly ALLO'O ALLO'O

Global Framework on Chemicals Focal Point, Gabon

Andrea GORE

Professor of Pharmacology & Toxicology, University of Texas at Austin

Linda S. BIRNBAUM

Scientist Emeritus and Former Director, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and National Toxicology Program, Scholar in Residence, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University

Robert Thomas ZOELLER

Professor Emeritus, Biology Department, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Leo TRASANDE

Jim G. Hendrick MD Professor of Pediatrics & Director, Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards, New York University Grossman School of Medicine

Maria NEIRA

Director, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Health, World Health Organization

Maureen SWANSON

Director, Environmental Risk Reduction & Project TENDR, The Arc | Co-Moderator

Pamela MILLER

Co-Chair, IPEN & Executive Director, Alaska Community Action on Toxics | Co-Moderator

Summary

This event is an opportunity in advance of INC-4 to understand the latest science and we have a great panel of both scientists and policy expertise represented. This knowledge then requires the need for strong, bold and urgent action to address the threat to children’s health.

Opening

Serge Molly ALLO’O ALLO’O | Global Framework on Chemicals Focal Point, Gabon

- Global governance of chemicals and hazardous waste is certainly marked today by the significant results achieved in the implementation of the Stockholm Convention on POPs as well as the Basel, Rotterdam and recently Minamata Conventions which provide a framework to protect human health and the environment from hazardous chemicals and waste through a life-cycle approach.

- 20 years after the entry into force of the Stockholm Convention on POPs, the majority of Member States of the United Nations have ratified and are implementing this Convention. This bears witness to the importance of its objective, which is to protect human health and the environment from the harmful effects of POPs.

- The information published by the Secretariat of the Stockholm Convention under the heading of information exchange shows that many countries, including those in the Africa, have taken significant steps towards achieving the objectives set. However, an in-depth examination of this commitment reveals a gap between the time taken to assess potentially dangerous chemicals, of which there are more every day, and the COP’s decision to eliminate them or restrict their production.

- Unfortunately, this time is not taken into account when it comes to measuring the impact on health and the environment. Similarly, it’s difficult to establish legal responsibility for the negative impacts that result. By way of illustration, this is the case for electrical and electronic goods, where plastic additives are listed as POPs. One example is brominated flame retardants, some of which are banned or restricted by the Convention, while a large number remain authorized pending political decisions, despite the evidence of scientific research. As can be deduced, their use continues.

- At the regional level, despite the existence of agreements such as the Bamako Convention, the problem remains unresolved. Over the last few years, the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (AMCEN) has decided to step up the action needed to monitor and assess the effects of hazardous chemicals. This is why it’s important to make the case for limiting risks throughout their life cycle.

- In the specific case of Gabon, the experience of implementing the Libreville Declaration on Health and the Environment in Africa, an action strongly supported by WHO and UNEP, has made it possible to identify and secure nearly 100 tons of PCB-type POPs with the support of the Stockholm Convention funding mechanism. This success was recognized by the Executive Secretary of the BRS Conventions, Rolph PAYET, at the 11th COP held in Geneva in 2023.

- The experience of implementing the Stockholm Convention has highlighted the importance of synergy between players in solving environmental problems. Indeed, the results achieved in Gabon in particular are the fruit of close collaboration between various partners, notably the United Nations agencies, including WHO and UNEP, with financial support from the GEF.

- As part of their strategy to support actions to protect health and the environment, in particular the implementation of the Libreville Deceleration on Health and the Environment in Africa, technical and financial support has been mobilized to set up integrated observatories for the prevention and management of chemical risks (ChemObs Africa) in nine African countries, including Gabon.

- One of the results of this project is the elimination of the tonnages of PCBs identified and secured in Gabon.

- Unlike other conventions that deal with chemicals or hazardous waste, we can safely say that the Stockholm Convention is being effectively implemented, despite the constraints that are sometimes described as non-compliance.

- While many countries, particularly developing countries, have initial NIPs and updated NIPs as indicators of their firm commitment to implementing the Stockholm Convention, the actual elimination of POPs and their identification in commercial goods remain both very costly and difficult, since the technical capacity for destruction and scientific studies are virtually non-existent locally, which reflects the inadequacy of the resources available through the support mechanism for these countries.

- To make the link with the future treaty being negotiated on plastics, Gabon, in collaboration with IPEN, conducted a study on the presence of POPs in children’s toys and plastic kitchen tools sold on the Gabonese market. The results showed high levels of brominated flame-retardant POPs, especially in children’s toys. This highlights the importance of focusing on the elimination of chemicals of concern in plastics and the need for non-toxic recycling, if recycling is to be part of the answer to plastic pollution in

the future treaty, which aims to end plastic pollution by 2040. - This is where the future plastics treaty will offer a unique opportunity to protect human health, by eliminating all chemicals of concern throughout the life cycle of plastics, as well as greater transparency on the chemicals used.

- Cooperation and synergies between the future treaty and the Stockholm Convention in particular, and other multilateral agreements on chemicals and hazardous waste, will be key to achieving this objective of protecting human health.

- Developing countries will need financial and technical support to implement the plastics treaty once it is adopted.

Health Science Expert Presentations

Andrea Gore | Professor of Pharmacology & Toxicology, University of Texas at Austin

Hormone System, Wide-spread exposures to children from plastic chemicals, and Inter-generational impacts

This presentation focuses on developmental and multi generational effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals, or EDCs, in plastics.

The latest guide to EDCs threats to human health « Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: Threats to Human Health« , was recently released by the Endocrine Society in collaboration with IPEN.

There are chemicals and plastics that are EDCs, interfere with hormones in their actions. Hormones in our body are required for the normal regulation of growth and development, metabolism, responding to stress, reproduction, as well as other functions. When these functions are perturbed by EDCs, this can lead to endocrine disorders such as diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular problems, reproductive disorders, certain cancers, and even brain and behavioral problems, because the brain is extremely sensitive to the body’s hormones.

In the IPEN and Endocrine Society Guide, we focused most on this females and phthalates as the classes of EDCs that are very commonly and still are used in chemicals. Over the last decades, the science on how plastics contain EDCs, which ones are there and how they act, has grown as well as our understanding of how important the environment is in the prevalence of disease. In fact, most human diseases are either caused or exacerbated by environmental factors as opposed to the genetic underpinnings.

There is a convergence of research from studies using cell lines, animal models, and epidemiological studies in humans that have led up to very strong evidence and very strong confidence that exposures to bisphenols and phthalates can lead to detrimental health outcomes. And numerous international scientific and medical organizations have called for stronger regulations. So along with the endocrine society, most of the international pediatrics, other endocrine organizations, reproduction groups, andrology groups, thyroid groups, are calling for these regulations in recognition of the effects of these chemicals on endocrine systems.

EDCs and plastic threatened vulnerable populations. Of course, when we’re exposed to EDCs at any stage of our lives, we’re liable to develop some sort of adverse outcome. But we’re particularly concerned about periods of development when the body is changing rapidly and where exposures to hormones are very tightly regulated and even tiny amounts of hormone exposures can have big effects later on in life.

Our point of view is that EDCs pose the biggest risk to pregnant women and the fetus during pregnancy to young children, to people going through puberty when hormones are also rapidly changing. We know that there are exposures within the room and, too infants because biphenols and phthalates can both cross the placenta and get to a fetus. These chemicals are detectable in amniotic fluid and umbilical cord blood, and there is direct exposure of these developing people to these chemicals, and there’s also exposures of the mothers and those can also change their hormones of pregnancy.

We have a theory that we work under in this field that is called DOHaD or the developmental origins of health and disease. This DOHaD hypothesis posits that the timing of exposure to EDCs is key, as I mentioned, fetus, infant child and puberty. But importantly, the manifestation of a disease or an adverse outcome may not be observed for years or even for decades. Take as an example, exposure to an EDC in the womb that may change how the reproductive system develops. People don’t try to reproduce until they’re in their twenties or their thirties, and only then might they realize that there’s an a reproductive problem that was potentially contributed to by early life exposures to EDCs such as biphenols and phthalates. We refer to these vulnerable stages as critical periods when there is the greatest developmental change in hormone sensitivity. Endocronologists also like to use the phrase the timing makes the poison. I’d like to differentiate that from the phrase that toxicologists use in regulatory testing. They say the dose makes the poison, meaning a higher dose is worse than a lower dose, but we prefer the timing makes the poison because even a very low dose during a critical period can have long term and physiologically relevant consequences.

We also know that EDCs can have impacts across multiple generations. When a mother is being exposed to plastics, her child whose she’s holding in her arms, that would be the next generation, the fetus in her belly is also the next generation. They are directly exposed to the chemicals, within the womb of the fee and within the fetus itself are the cells that are going to be developing into the sperm or the egg cells, and we call that the germ line. We know now that germ line exposure to EDCs including these biphenols and phthalates can act upon the germ line cause, molecular changes and potentially lead to further generational effects if heritable to the next generation, what is the great grandchild or in the lab we call the F3 generation.

We are starting to understand the mechanisms by how these multi generational effects work. The germline, these precursors of sperm eggs can be programmed by EDCs. We use the word programming affecting multiple generations, and this programming is referred to as « epigenetic programming », and the way this works is that they are changes to the DNA that happened through exposure to BPA or phthalates or other bisphenols. They’re not mutations, we’re not changing the DNA sequence that encodes a gene, what we’re changing are other factors around the gene within the cell that modify whether that gene is going to be expressed and whether that gene will then be turned into a protein, and the protein is the functional unit that would carry out functions in the body that would be stimulated by hormones.

Some of these mechanisms are known for heritability. They’re called DNA methylation, histone modifications and non coding RNAs. We know now that germline exposure to EDCs can undergo any of those modifications and then transmit an adverse endocrine or neurological phenotype to the next generation.

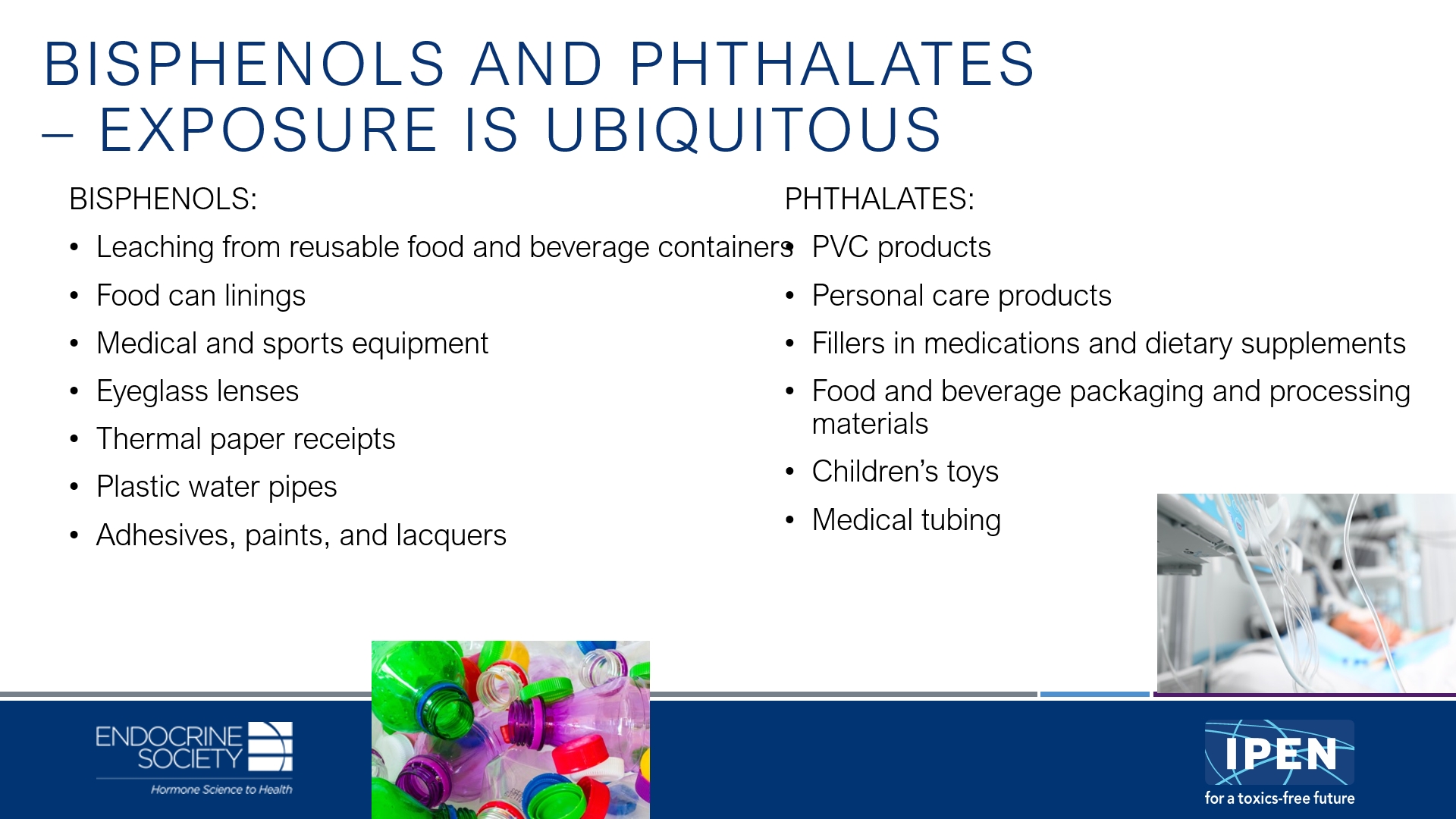

Bisphenols and phthalates are ubiquitous in the environment and just for the sake of time. They come for many different sources.

Although they’re not POPs, our exposures are so ubiquitous and we are constantly being reexposed, and so they might as well be POPs in the sense that while the chemicals themselves are not persistent, we have constant exposure to these kinds of chemicals. When we see something that is BPA free, it almost always includes a replacement bisphenol such as BPS, BPF or BPAF, and those are also now known to be EDCs, and similarly, there are phthalates that are replacing other phthalates, and we call this a regrettable substitution cycle where one similar chemical replaces another and we’re not really improving health outcomes. We also know some of the mechanisms. BPA is well studied for its effects on estrogen receptor and phthalates for their effects on the androgen receptor and their respective hormones are estrodial and testosterone. But these are just the typic of the iceberg on how these chemicals act as EDCs.

For the human health outcomes that are linked to phthalates and BP and bisphenols, there is very strong evidence for direct developmental exposures and increasing evidence for intergenerational effects on brain disorders, metabolic problems like diabetes and obesity, reproductive health problems, and reproductive cancers, thyroid hormone problems, and cardiovascular disease and hypertension.

All of these are covered in the IPEN guide, and the two Endocrine Society scientific statements:

- Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: Threats to Human Health | Endocrine Society and IPEN | February 2024

- Plastics, EDCs & Health | Endocrine Society and IPEN | December 2020

Linda S. BIRNBAUM | Former Director, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and National Toxicology Program, Scholar in Residence, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University

Protecting the Developing Brains of Children from the Harmful Effects of Plastics and Toxic Chemicals in Plastics: the Latest Science and Need for Policy Change

This presentation will briefly go over the briefing paper that was just produced « Protecting the Developing Brains of Children from Plastics and Toxic Chemicals in Plastics« , and insist on the need to protect the brains of our children.

We need to understand when we’re dealing with plastics that the issue is not just the big plastics that we see out in the trash, but mainly all the fragments, the nanoplastics and the microplastics we are exposed to. It’s not only the physical issue that we have with the plastics penetrating into our bodies and then into our cells, but there are thousands of chemical additives. Some of these are very well known, the neurotoxicants such as the phthalates and the bisphenols. There are also the flame retardants, and in this presentation we are mainly talking about the PBDE flame retardants, most of which have been removed from commerce by the Stockholm Convention as well as other regulatory approaches. However, we all have them in our bodies and we’re still being exposed.

We have many other neurotoxicants that are present. They may not have quite as much data, but we know that they do cause problems in cells, in experimental animals, and there’s growing human data as well. There are other kinds of organohalogen flame retardants. There are the organophosphate flame retardants.

Why would we think that organophosphate pesticidides are bad for the brain of developing children, and we know that that’s the case and why wouldn’t we think that just because they’re not pesticide, they’re flame retardants, they would not also be bad for the brains of our children. There are other persistent chemicals like the chlorinated paraffins, the data for those just starting to emerge, and then the huge class of PFAS that many of us are very concerned, the Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances that are everywhere in everything and in all of us.

Plastics act as vectors to directly deliver these neurotoxic chemicals into our bodies and into our brains. It’s when we talk about how are we, what are our sources and how are we getting exposed, we need to realize we’re getting them from all routes. Plastics are present in our diet and many of the chemicals leached directly from the plastic packaging, the food processing equipment. Higher levels are found in fast food than, for example, organic food from the residents and cans and the bottles and getting to our died and therefore into us. These chemicals don’t only get into our food, they get into our dust, whether it’s our house dust or our office dust, and there can be very high concentrations in dust in the floor, in the building products, electronics, and so on. A lot of these are flame retardants as well as the phthalates.

We need to understand that when we try to get rid of plastics with incineration it is a huge problem because if in fact you have chlorine or bromine that can generate neurotoxic chemicals like our « old friends », that’s a little cynical, dioxins and furans. We know the children are highly exposed to things like dust because they spend a lot of time on the floor, but constantly mouth things and put things in their hands. Young children breathe and eat and drink a lot more relative to their body weight than adults.

We can find pieces of plastic, the microplastics and the nanoplastics, and these chemical additives in the plastic in the placenta, which is absolutely the organ that is essential for supporting the growth of the fetus. A recent study in fact found that 60% of placenta samples had plastic particles in 2006. Ten years ago, in 20213, it was ninety percent and in 2021, every single placenta looked at had plastic particles. We can find plastic particles and some of the chemical additives in macomium, which is the infants first stool. We find that these compounds in breast milk, and we find them in inform formula as well. The blood brain barriers are very, very weak barrier and plastic particles can directly cross into the brain. Babies entered the world today with their brains and bodies contaminated with plastics.

Some of the impacts on child brain development? Plastic particles as well as the chemicals, can penetrate across cell membranes and impair placental function. If you impair the placenta, you’re gonna have impacts on:

- fetal growth,

- brain growth and development,

- behavior, on motor function, on learning, and in memory.

We know the plastic particles have been found in all the placentas of low birth weight babies. But many fewer were found in normal weight babies. Babies with higher microplastic exposure had lower birth weights, shorter length, and a smaller heads circumference, and a lower Apgar score.

So there is overwhelming evidence of neurotoxicity for several classes of chemicals. that are present in plastic and these show that prenatal and early childhood exposures contribute to problems with child brain development and neural development disorders. Phthalates, the PBDE flame retardants and the bisphenols achemical classes and their substitutes leach into our food and into the dust, we’re finding them in pregnant women, in infants, in children. They do cross the center and access the infant via breast milk and formula.

Why do we have phthalates? Because they make plastics more flexible and more durable. They’re used in food packaging and production materials, personal care products, flooring, walk coverings, all kinds of medical devices.

Youngest children have the highest level of allied exposure of any group in the population. But we know today that diet accounts for more than fifty percent of the exposure at least in the US. And we know that prenatal exposure to the phthalates is associated with impacts on IQ, behavior, attention, and there are repeated studies showing links to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Some of the most interesting and concerning evidence is that phthalate exposure prenatively can also affect the brain structure. You can actually measure changes in brain volumes and these are linked to IQ deficits.

It’s important to remember that we have this whole history of unfortunate substitution and emergency evident emerging evidence is showing that the replacement phthalates also harm child brain develop development.

The organicalogen flamor targets are a huge class, added to furniture, textiles, electronics, to reduce the spread of fire or the ignition actually of fires. The class that we have the most information on are the PBDEs, and they are associated with learning behavior and intellectual impairment. We’re also finding the children who are on the autism spectrum, maybe more susceptible to the flame retardants than children who are not on the spectrum.

Now PBDEs abandoned internationally. The US restricts some uses of PBDEs, but the problem is they’re everywhere. They are found in recycled plastic products, including toys, food containers, and food handling utensils. Unfortunate substitution, other BFRs, brominated flame retardants, and organic organophosphates flame retardants have replaced the PBDEs. These replacement also show harm to child brain development. They impact fine motor skills, working memory language abilities, behavior, and attention.

We have overwhelming evidence again, these are tremendously high production volume compounds that are used primarily in polycarbonate plastics, hypoxy resins. They’re also present for example in thermal paper. Their neurotoxicity has been extensively studied both in animal models like rats and mice, and in human studies. Exposure to rodents during pregnancy, infancy or adolescents is linked to deficits and memory and learning abilities, and the human studies show that BPA, like phtahalates, contributes to ADHD, autism depression anxiety, and cognitive disorders and children. What’s especially concerning is that while we started to move from BPA to some of the substitutes like BPS, BPS, BPAF, those substitutes untested before we move to them, show larger impacts on childbrain development than BPA.

We really have to talk about preventing regrettable substitution. Emerging evidence shows that replacement chemicals are just as more or more neurotoxic and the levels of these replacement chemicals are increasing in the population, including in pregnant women and children. If we’re gonna prevent harm to children’s brain, we need to eliminate all non essential uses of plastics and harmful caresses of chemicals, rather than trying to eliminate toxic compounds one by one.

Tender does have some recommendations related to the global plastics treaty. We need stakeholders to demand:

- To substantially reduce and cap plastics production, we need to eliminate move towards elimination of single use plastics and other non essential uses.

- To phase out use of the most toxic plastic polymers, things like polyvinochloride and polystyrine.

- To phase out the addition of neurotoxic chemical classes in plastics:

- Immediate bans on these chemical plastics from food contact materials since that is a major exposure to the population,

- Ban the classes of toxic additives in plastics and avoid regrettable substitution.

- To ban intentionally added nanoplastic and microplastics in products such as cosmetics, cleaning products and toys.

- Require full transparency and full public disclosure of information, including identification and reporting of all chemicals used in plastic production as well as plastic additives.

- Ensure that disposal and recycling of plastics does not result in toxic substances and that toxic substances are not present in recycled plastics.

- Prevent incineration of all plastics, including chemical recycling, advanced recycling, and waste to energy schemes.

We need a plastic treaty that protects the health of all people, but especially our children. We call for a strong plastics treaty that protects the health of children’s developing brains by reducing the production and use of plastics and subsequent generation of plastic particles, and by preventing the harmful effect of plastics throughout their life cycle.

R. Tom Zoeller | Title Professor Emeritus, Biology Department; University of Massachusetts Amherst

How Chemicals in Plastics Interfere with the Actions of Hormones that are Critical for Brain development

This presentation will focus on how hormones work. Hormones can only act on cells that have the right receptor. This receptor is a protein that can be either on the outside of the cell or the inside, and it’s often thought that the affinity of the receptor for a chemical or the hormone is the same as potency or defines potency, but this is not correct.

One thing that this graph shows , if you look at for example the agonist or hormone concentration of ten to the minus seventh molar and follow the line upwards and shows that a cell that has more receptors has a greater response. In addition to only achieve ten or twenty percent response in the cell, you need less and less agonists by many orders of magnitude to create that as cells have more receptor numbers.

What this means is that different tissues are differentially sensitive to hormones as well as sensitive at different times during development. But it’s also true that they are differentially sensitive to endocrine disrupting chemicals or neurotoxicants in in the case here.

Thyroid hormone is essential for brain development and for physical development, as it contains iodine and iodine deficiency in human populations globally is the single greatest known cause of brain damage, which is not reversible. Fetal brain development requires thyroid hormone even during the first trimester of development. This is before the fetus can make thyroid hormone, which means that the only source of thyroid hormone is the mother. It’s still important to recognize that thyroid hormone is essential throughout development especially during the neonatal period.

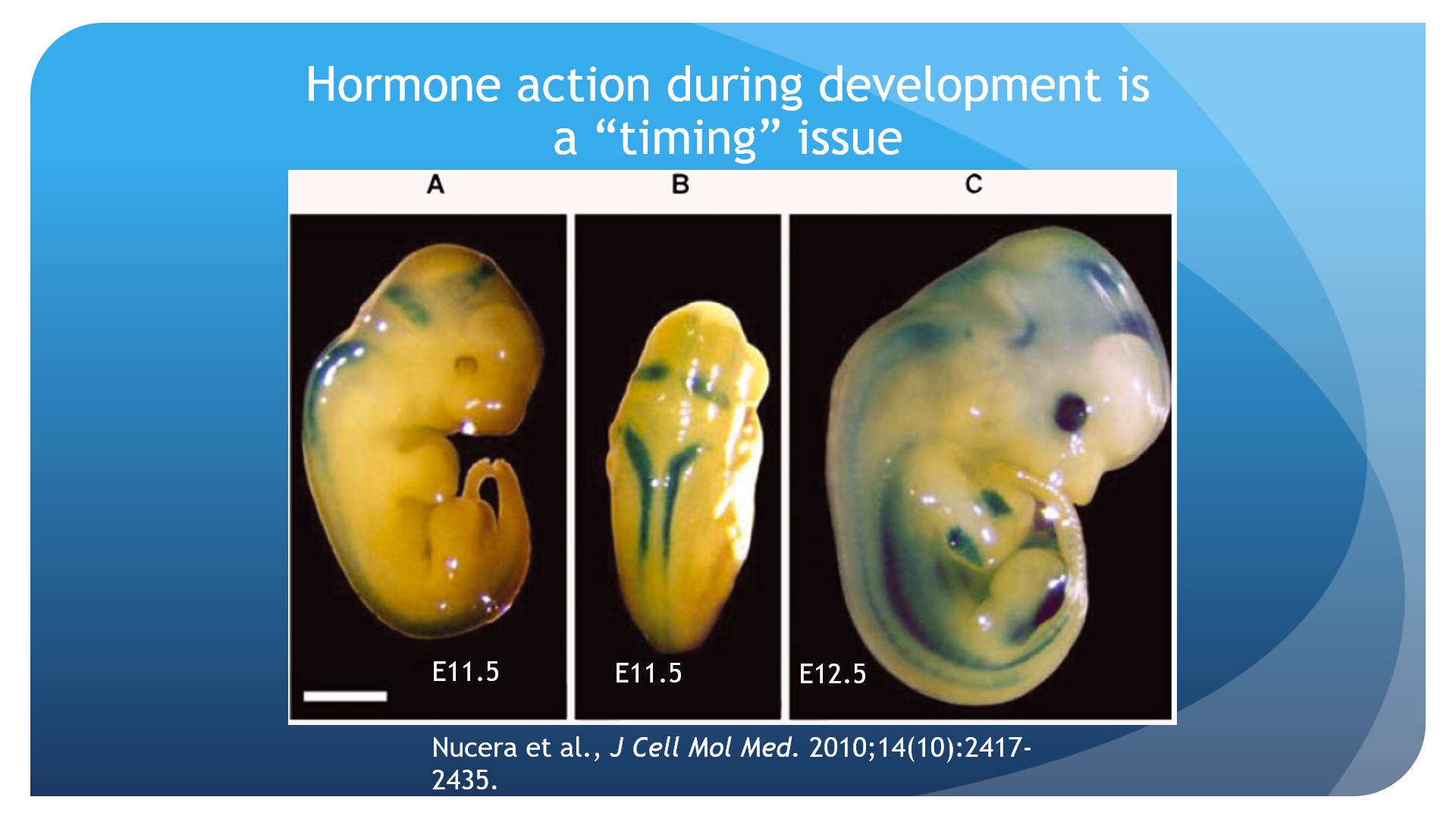

An example to show why doctor Gore’s statement about how timing makes the poison is true for EDCs. In the image below you see mouse embryos at different times during development.

Embryonic Day 11.5 and 12.5, just twenty four hours different. The blue color here represents where the thyroid hormone receptor is being activated. If you look at the eye, you can see that on 11.5 the eye has no activation of thyroid hormone receptor, but on 12.5 it’s quite abundant, illustrating how timing is so important for proper development.

This is also expanded kind of in a review article with Joanne Rovet (Timing of Thyroid Hormone Action in the Developing Brain: Clinical Observations and Experimental Findings | R. ZoellerJ. Rovet | Published in Journal of neuroendocrinology | 1 October 2004) who has worked for many years on human populations with thyroid hormone insufficiency.

What this shows is that thyroid hormone insufficiency at different times during development produces deficits in various cognitive functions, visual processing, gross motor skills, executive function, etc. The same is true in animal studies that have looked at different elements of brain development.

What we know for a certain:

- Interfering with hormone action during development will have permanent consequences. You simply cannot reverse problems in development that occur early on.

- People listening to this talk, for example, would not have the intellectual capacity to understand it if you had been deficient in thyroid hormone during development. It’s clear that, that early on when children were born without a thyro without a thyroid gland, if they had not been identified and treated soon enough, their IQ would be in the fifties rather than a normal of a hundred.

- You wouldn’t have the intellectual capacity even to develop your career.

- The impact that you’ve had on your scientific or other discipline wouldn’t be the same.

- Plastic plastic chemicals that interfere with thyroid hormone system represents this existential threat because it severely reduces our ability as a human population to function.

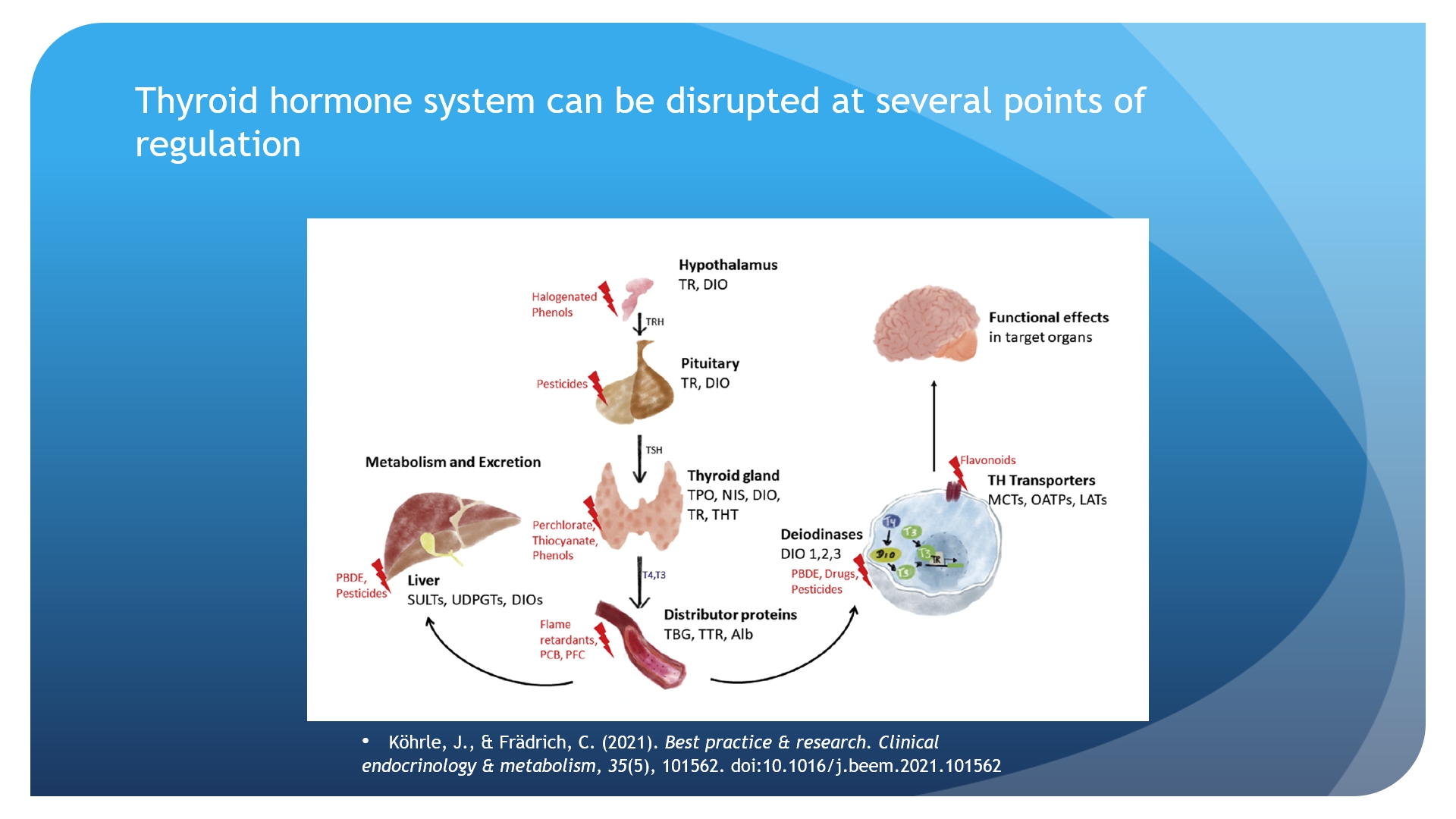

We’ve talked about a traditional view of the hypothalamic pituitary thyroid access, but it’s important to recognize that this is a very complex system that requires even mechanisms within individual tissues that control thyroid hormone action.

One of the outcomes of this recognition is that toxicants can interfere with thyroid hormone action in selective tissues without affecting hormone levels in the blood. So we can’t assume that hormone levels are changes in hormone levels for thyroid hormone in the blood is predictive of changes in hormone action in various tissues. This represents a very complex issue that that is difficult to identify in an all cases.

Plastic chemicals are known to interfere with the thyroid hormone system. You’ve heard about phthalates, biphenols, triclosan, halogenated flame retardants and PFAS. And while these represent just a few of the chemicals that are known to be in plastics relative to the estimated 16’000 different chemicals that are used to make plastics, they’re important because we are all contaminated with these chemicals.

Leo Trasande | Jim G. Hendrick MD Professor of Pediatrics & Director of the Center for the Investigation of Environmental Hazards, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, USA

Preterm Births Linked to the Plastic Chemicals

Most of the presentations have focused on children’s learning and development and the consequences of chemicals used in plastics in particular. And as Doctor Birnbaum described so eloquently, we visually put our attention most firmly on what we can see in oceans and now in humans specimens in the form of microplastics. But it’s more than likely that the reason why microplastics are a problem is that they are the chemical carrier pigeons, ultimately, and deliver toxic drugs to key organ systems crucial for children’s learning and development. Perhaps we should have known this given the advent of nanotechnology as a therapeutic pathway for delivery of drugs into people’s bodies, and by the same token nano and microplastics can deliver toxic chemicals that don’t just affect children’s brain development, but affect all sorts of organ systems that span the life course.

Doctor Birnbaum also described studies documenting the presence of microplastics in the placenta. When you see microplastics, you see a much larger array ultimately of chemicals that are in, and absorbed directly, and crossed the placenta and into children’s bodies. It’s not just effects on thyroid development and developing brains that are problem. Those chemicals used in plastic materials disrupt hormonal function in the placenta and contribute to inflammation directly in the placenta.

The Placenta is the organ that keeps gestation going. Every week in a child’s gestation is crucial, not just for brain development, but ultimately for development of all sorts of organs. The effects of a shorter gestation are permanent and lifelong. That’s why we focus most keenly on prolonging gestation all the way to term. And we know that children who are born preterm don’t just have cognitive deficits. They ultimately have long term cardiovascular metabolic risks all the way into adulthood. When you have inflammation in the placenta, you limit blood flow to key and vital organs. We learned in the aftermath of World War II that there are these developmental origins of health and disease that doctor Gore described.

The work of the later David Barker documented that when you disrupt fetal growth, the consequences can be as significant as cardiovascular mortality and even stroke. It’s not just gross disruptions of fetal growth that can have those consequences for adult health. We know, that subtle consequences such as the ones we’re talking about here with low level chemical exposures can disrupt certainly key moments in fetal growth, and then reverberate longer term through a thrifty fetotype in which the child out of the womb is avidly absorbing calories in a way that has adverse consequences for obesity as well as heart disease.

We have done a study documenting validate exposures in a large sample of American children, spanning five thousand children from across the country. We found:

- Chemicals as they’re introduced in plastic, whether we replace one chemical with another, have the same consequences, in even potentially worse consequences for a prematurity. Some of the older phthalates used in food packaging such as bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate or DEHP had already been associated with prematurity and shortening gestation. What we found in this large study published in Landset Planetary Health this year is that the replacements DiNP, DiDP, and DnOP, were all even more strongly associated with shortening gestation and increases in premature birth.

- The substantialness of the impact of Phthalates on premature birth. We’re talking about 5 to 10% of all premature births in the United States, extrapolated based on current exposures we see in the US. The global consequences are likely as similar, it’s just a question of documenting the exposures to phthalates.

What we found is that the costs of these premature bursts are in the range of 5 to 8 billion US dollars a year. That’s an annual cost in so far as exposures continue at current levels. Now this adds to the cost of disease and disability ultimately that can be traced to chemicals used in plastic exposures. In the Journal of endocrine society, we published a paper this year reflecting on the costs. Isolated the disease burden and cost that could be traced ultimately to chemicals used in plastic. And what we found were costs on the order of 250 billion dollars a year. That’s separate from that 8 billion dollar cost in the United States alone. That was based on less than 1% of chemicals used in plastic, a subset of diseases due to the few chemicals we studied and a subset of costs due to the few diseases due to the few chemicals we studied. This is therefore an extreme underestimate of the broader consequences. Just isolating in the United States, if you extrapolate globally, we’re talking potentially in the range of trillions of dollars of economic costs due to disease and disability, especially in children, because the largest driver of those two hundred fifty billion dollars in costs were ultimately adverse effects on brain development.

We need to get serious about reducing our use of plastic, particularly our production of plastic. Because recycled plastic can accumulate greater amounts of chemicals as have been demonstrated in previous studies. The whole recycling notion is a failure of consumerism. As far as we don’t reduce our use of plastic, we won’t reduce the disease burdens that I’ve talked about because the chemicals will be there, from the plastics and will be drug delivered ultimately into children’s lives but in ultimately in all of us.

We need to reduce our production of plastics period. We also need to simplify the chemical composition of plastic. We have 16’000 chemicals used in plastics today. We can’t study all sixteen thousand, but little we know about twenty to thirty suggests huge consequences described here for human health and for the economy. Ultimately, if we go testing every single one of these chemicals, the fear is that we will have an even greater consequence for human health. It really speaks to the need to hone in on a subset of chemicals that are truly identified as safe ultimately. We need to put the burden of safety on the chemical rather than on people’s lives.

We need to identify and follow as the plastics treaty is implemented what chemical exposures from plastics are like in low and middle income countries in particular. We have extreme gaps in data in what is the burden of disease and disability and the exposure, as a result of chemicals used in plastics. We need to have a biomonitoring system put into place to document chemical exposures of concern. We need to build more science, we need a global infrastructure, ideally, through a an equivalent of an international agency for research in plastic chemicals in particular endocrine disrupting chemicals. That’s really going to be our pathway to pass a legacy onto the next generation of children that is better for the first.

Maria NEIRA | Director, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Health, World Health Organization

The World Health Organization is very much supportive of outlining the importance of the plastic treaty.

The plastic treaty represents an opportunity to protect people’s health, and that’s why we will be very happy if in the treaty there is even more recognition of the importance for public health, and not only the threats for public health. It will be very important as well to highlight the benefits for health that we can obtain if such a treaty is properly implemented. WHO will make sure that all the WHO resolutions, papers, norms, standards, and scientific networks can contribute to making this treaty stronger and more protective of our human health.

In fact, we see that one of the exemptions that is proposed is for the health sector for all the medical products, but on that we think that there is no need of a blanket exception for those medical products. On the contrary we are moving into the ATACH platform, which is the Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate change and Health where we have put in place a working group, a big initiative, a platform to reduce plastic use to decarbonize the health sector and we can offer a lot of knowledge and initiative and action on reducing the plastic when it’s not needed on medical devices or procurement and supplies that we use at the health sector level.

We will be looking at what we do internally that can support, such as the tobacco framework convention, which is looking at the plastic filters of the cigarettes and they are going very much on pushing for even a ban. They have requested a group of experts to produce a recommendation regarding the potential legislation. This type of work has to complement the plastic treaty, we don’t need to duplicate and we can join forces very strongly on that.

This is all about prevention and you know that prevention is always very difficult to implement. And primary prevention is so difficult, imagine when you don’t see the manifestation of the diseases only occurring after years of disposure. Therefore we need to be very pragmatic on this plastic treaty telling people that when we don’t need those plastics, they can be eliminated and by doing so, we will be having a a very positive impact and protecting people’s self. WHO is very much committed and we will put all the health arguments, the threats, and the benefits together to support a strong agreement and a strong implementation of the plastic treaty.

Discussion

The panel was followed by a questions and answer session.

Highlights

Video

Documents

- Presentations made during the event

- Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals: Threats to Human Health | Endocrine Society and IPEN | February 2024

- Plastics, EDCs & Health | Endocrine Society and IPEN | December 2020

- Protecting the Developing Brains of Children from Plastics and Toxic Chemicals in Plastics | TENDR Briefing Paper | April 2024

- Prenatal phthalate exposure and adverse birth outcomes in the USA: a prospective analysis of births and estimates of attributable burden and costs | The Lancet Planetary Health |Leonardo Trasande, MD et al. |February 2024

- Chemicals Used in Plastic Materials: An Estimate of the Attributable Disease Burden and Costs in the United States | Journal of the Endocrine Society, Volume 8, Issue 2 | Leonardo Trasande, Roopa Krithivasan, Kevin Park, Vladislav Obsekov, Michael Belliveau | February 2024, bvad163