Événement Virtuel

Road to OEWG 2 | Developing Operating Principles of the Science-Policy Panel on Chemicals, Waste and Pollution Prevention / SPP-CWP Series

26 Apr 2023

13:00–14:30

Lieu: Online | Webex

Organisation: Groupe de travail spécial à composition non limitée chargé d’examiner la création d’un groupe d’experts sur l’interface science-politiques au service de la gestion rationnelle des produits chimiques et des déchets et de la prévention de la pollution, Geneva Environment Network

In the lead-up to the establishment of a science-policy panel (SPP) to contribute further to the sound management of chemicals and waste and to prevent pollution, a series of webinars and events are being launched by the ad hoc open-ended working group (OEWG) Secretariat and the Geneva Environment Network to build bridges and promote collaboration and knowledge sharing between and among stakeholders, and to raise public awareness about the OEWG preparing proposals for the establishment of the panel.

About the Session

This webinar is in direct response to a request from member states at the resumed first session of OEWG for inputs on the operating principles of the new panel. During the webinar, the OEWG Secretariat presented on how principles have been set out in the broader context of other rules, procedures and guidelines. A background document to support discussion on operating principles was also made available in advance of the webinar.

This presentation and background document are informed by concepts already included in UN Environment Assembly Resolution 5/8 (Science-policy panel to contribute further to the sound management of chemicals and waste and to prevent pollution). While the science-policy interfaces of conventions addressing chemicals, waste and pollution do not necessarily include stand-alone text detailing principles, the OEWG Secretariat also continues to review their processes to ensure that the proposed operating principles of the new panel align with principles underpinning the conventions’ work on chemicals, waste and pollution (including for example the Montreal Protocol on ozone-depleting substances and the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants).

Participants in the work of four existing science-policy presented on their respective panel’s reliance on principles: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), International Resource Panel (IRP) and Global Environment Outlook (GEO).

Member States are invited to provide submissions on a set of operating principles for the SPP through their respective national focal points, to be presented at OEWG 2 in December 2023. Non-government stakeholders are invited to submit their submissions on behalf of their organization or group.

Road to OEWG 2 Webinar Series

As a follow-up of the resumed first session of the OEWG, a series of webinars, co-organized by the Secretariat of the OEWG and the Geneva Environment Network, was launched. The webinars aim at building bridges and promote collaboration and knowledge sharing between and among stakeholders, and to raise public awareness about the OEWG preparing proposals for the establishment of the panel.

Speakers

By order of intervention.

Gudi ALKEMADE

Chair, SOEWG on a Science-Policy Panel on Chemicals, Waste and Prevention of Pollution | Deputy Permanent Representative to UN Environment Programme, Netherlands

Jacqueline ALVAREZ

Chief, Chemicals and Health Branch, UN Environment Programme | Moderator

Ko BARRETT

Vice Chair, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change | Senior Advisor for Climate, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Mar VIANA

Co-chair, Multidisciplinary Expert Scientific Advisory Group (MESAG), Global Environment Outlook | Institute of Environmental Assessment & Water Research, Spanish Research Council

Hala RAZIAN

OiC Head of Secretariat, International Resource Panel

Eduardo BRONDIZIO

Co-Chair, Global Assessment, Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

Highlights

Video

The event was livestreamed via Webex.

Summary

Welcome & Introduction to the OEWG

Gudi ALKEMADE | Chair, OEWG | Deputy Permanent Representative to UN Environment Programme, Netherlands

I facilitated in my capacity as Deputy Permanent Representative in the negotiations that led to the resolutions that form the basis of our work towards the establishment of the panel. This is the first of a series of webinars to inform member states and stakeholders on important elements of the work ahead and that we need to deliver at the end of this process. We hope these webinars and some of the side events will serve as a basis for written submissions by member states and stakeholders and inform informal consultations and our discussions in the next session. I hope this webinar will enhance a common understanding of what the operative principles should be, what they are, and what should be addressed in them, as well as how they could be addressed.

Presentation from the OEWG Secretariat | Operating Principles: Learning from previous practice

Jacqueline ALVAREZ | Chief, Chemicals and Health Branch, UN Environment Programme

This webinar is intended to provide a snapshot, a quick idea, and an understanding of the look and feel of operating principles. Operating principles are a direct response to the request that we have received in UNEP to prepare for further discussions at the end of this year in Jordan. During this webinar, you will also see how things are interconnected, and though we are going to focus on operating principles, they cannot be seen as a standalone process or document that will be revised. They need to fit into the bigger picture, which is this new panel that will be part of the discussion.

When we are looking or thinking about operating principles, maybe not everybody is on the same page and on the same level of understanding, but when drafting them, there are some considerations that are important to have in mind. For example, consider how they may shape the long-term flexibility of the panel’s work, the institutional arrangements that might be related and coming as a consequence of the operating principles, the form follows function concepts and ideas, the rules, the priority setting schemes or criteria that might also be part of it. Operating principles are a crucial building block to ensure the relevance of the work over time in a transparent manner. They provide an enabling platform to discuss, generate knowledge, and facilitate the important uptake that follows.

What are operating principles and why do we need them? | There is no one-size-fits-all proposal. We are creating a new panel, which means we can learn from the past but we have the possibility to shape the future. Going through the principles of existing panels all of them are valid. All panels follow common principles that are targeting the credibility, relevance, resilience, legitimacy, and transparency of the work. In other words, it is also about how detailed and explicitly they are presented. The inclusion of operating principles among the different science policy panels can be seen as a means of recognizing an agreement on overall priorities, characteristics, and values that will shape the panels’ outputs and deliverables.

Learning from previous practice | Today, we will learn and hear the hiccups and best practices as well from recognized speakers. The science policy panels define operating principles according to different things, the to-do and the not-to-do things. There is a background document that has been shared with you. You will benefit from the different explanations in a simple manner.

- IPCC approach to principles | The Science Policy Panel on Climate adopted the first IPCC work plan in 1998 and was amended in 2012. The IPCC principles lasted several years, meaning that they were strong enough to guide the work of the panel for a long time. The principles are connected to the rules governing the IPCC work. The operating principles are one piece of the puzzle, one building block in the whole setup.

- IPBES approach to principles | There are eleven items included in a document that the IPBES has produced, titled “Functions, Operating Principles, and Institutional Arrangements of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.”. This document was adopted in 2012 by the plenary. In this session, the IPBES panel was formally established.

- IRP approach to principles | the guiding principles of the IRP were adopted in 2016. In here, they have a list of five terms, each followed by a brief elaboration of what they mean.

- GEO approach to principles | The operational principles were recently adopted in September 2022, following a resolution by the United Nations Environment Assembly. This aimed to refine the approach to the Global Environment Facility, focusing on objectives, core functions, and increased effectiveness in preparation and implementation.

Policy-relevant and not policy-prescriptive aspect | Some things are already pre-established in the resolution 5/8 that was adopted one year ago. It talks about delivering policy-relevant scientific evidence without being policy prescriptive. It presents a range of possibilities and options for changing behavior, adjusting aspects, and better understanding the status and state of knowledge in certain areas. The policy-relevant, but not policy-prescriptive aspects are already reflected in the IPCC, but also in the IPBES, in the IRP, and in the GEO process. However, in the GEO process, it’s talking about relevance in general, responding in a flexible manner to the needs of member states or other stakeholders might need. This is an essential feature that the UNEA resolution and the member states were targeting so that the policy uptake can be done at different levels, at the government level, but also in those enterprises, in those consumers, and in the people that can really be the agents of change.

Inclusivity/Balance of representation | It encompasses indigenous peoples, geographical regions, gender balance, interdisciplinary activities, and multi-sectoral stakeholders. This aspect is consistently found across the panels we discussed today.

Integrity/Objectivity/Independence/Lack of Bias (conflict of interest) | Only the IRP principles document explicitly calls out the issue of conflict of interest, this was a special request from the open-ended working group meeting and participants that discussed and negotiated in Bangkok two months ago. Those elements are critical for the future. They are independence, objectivity, unbiased, and integrity of the scientific processes.

Cross-cutting themes | Credibility, relevance, and legitimacy, are core to any panel. The cross-cutting themes of transparency, flexibility, and coordination without duplication or complementarity with others, including MEAs, are also essential. Here, perhaps a point of reflection concerns alignment in our work plans. Sometimes, we must genuinely evaluate our current position and determine how we can collaborate more effectively, regardless of the topic being addressed. We should identify areas where a science-policy panel might be able to offer expertise through the work being done by others while ensuring cost-effectiveness. This is crucial for making well-informed decisions that enable us to advance the agenda

Other concepts that might potentially be included under principles of the panel

- Innovation: It’s a topic that still is in its early stages. There are many opportunities, but we lack scientific statistics or data on the uptake of those innovations.

- Comprehensive/Holistic/Integrative: There are a lot of examples, a lot of good practices, and many principles around what sustainable and green innovation might mean, but it might also be very important to reflect on this in the context of a science-policy panel.

- Consensus-based: is also part of the spirit of international governance discussions, where decisions need to happen in a concerted manner, not leaving anyone behind.

- Accessibility: if the data, the results, the assessments, and the strategies are not accessible, they will probably not have the impact that we are looking to have.

Going into the process & call for written submissions | There are ongoing discussions about advancing the various building blocks in this agenda. In the case of the operating principles, a specific process has been outlined, which begins with this webinar as an overview of the commonalities. We will hear from experts with diverse experiences in different agendas, but please note that a background document is already available for review. So, this is not the first step, as some work has been done previously. That paper will require your comments, submissions, and input, and you will receive an official communication. Member states, focal points, and other stakeholders, including those beyond the government level, are invited to participate in this process. We request your submissions be sent no later than June 6th this year. Finally, preparations for the open-ended working group meeting are underway, which is expected to take place in Jordan this December. To ensure a smooth process, please submit all necessary documentation in a timely manner.

Stakeholders Perspectives

Ko BARRETT | Vice Chair, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change | Senior Advisor for Climate, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The IPCC has been in existence for over thirty years, and our core action is to provide periodic assessments of the state of climate knowledge. We put out our assessment products about every seven years, and we’re now just finishing up our sixth assessment cycle. I will focus on just three of our core principles that drive the way we work.

Operating Principle 1: policy-relevant, but not policy prescriptive | It means making sure to assess the science that is so key to underpinning solid policy decisions, but not to do so in a way that actually criticizes or even evaluates the specific policies of regions or countries. It’s an interesting evolution that’s gone on in the IPCC because as we move towards stronger climate action, policymakers have been asking us to assess the feasibility of some of these actions. So we do so, and that’s actually become an important part of our recent assessments, but we never do it in the context of what an individual policymaker or country is employing. It’s key, because we need to maintain always our scientific integrity and an unbiased approach.

Operating Principle 2: The Important Role of Broad Review and Consultation in Achieving Consensus Support for our key summary findings | During the production of our assessment reports, we have various reviews. Some of them engage scientists and experts; other reviews are geared specifically to governments. We find that this broad review of our draft reports helps us to check biases that we, as scientists, may have, but also to write the reports in ways that are more accessible to, say, a non-science reader. It helps also to start building broad support for our summary findings, which we negotiate with governments word for word in our summaries. I think the power of IPCC reports is that we then have consensus between policymakers and science on our key findings.

Operating Principle 3: the importance of diversity and inclusion for our process. IPCC assessments are global assessments of the state of knowledge for climate, as such, we need to be inclusive in the scientists that we engage in authorship. We’re very keen to reach equity in terms of gender and in terms of bringing in scientists from the global South. We find that this inclusive approach actually helps to make our assessments much more broadly useful. It helps us to check cultural biases that may be introduced by having too narrow a group of scientists, but it also helps to broadly educate the world on the importance of these findings. As we go along, just taking gender as an example, when we first did our first assessment report in the late eighties, we had about three percent women as part of our authorship team. Now, we’re not at fifty percent, but we are over thirty percent in the number of women scientists that we engage in our process. We only grow stronger, and the reports only become more robust with the inclusion of a broad range of scientists and stakeholders.

Mar VIANA | Co-chair, Multidisciplinary Expert Scientific Advisory Group (MESAG), Global Environment Outlook | Institute of Environmental Assessment & Water Research, Spanish Research Council

I will present some of the operating principles of GEO, some facts and how it works in terms of actors and roles. GEO sources from the mandate of the UNEA Resolution 5.3, which has an objective to keep the world environment situation under review to inform and support action. It means to be active while strengthening the science-policy interface of UNEP, and this should be done by governmental expert-led assessments produced every 3-4 years, which is the Global Environment Outlook, the GEO.

GEO is UNEP’s flagship intergovernmental and expert-led integrated environmental assessment. It is viewed by member states as a foundation of the unified policy interface.

GEO shares a set of operating principles that are common to many major assessments because it builds on best practices and experience from previous assessments.

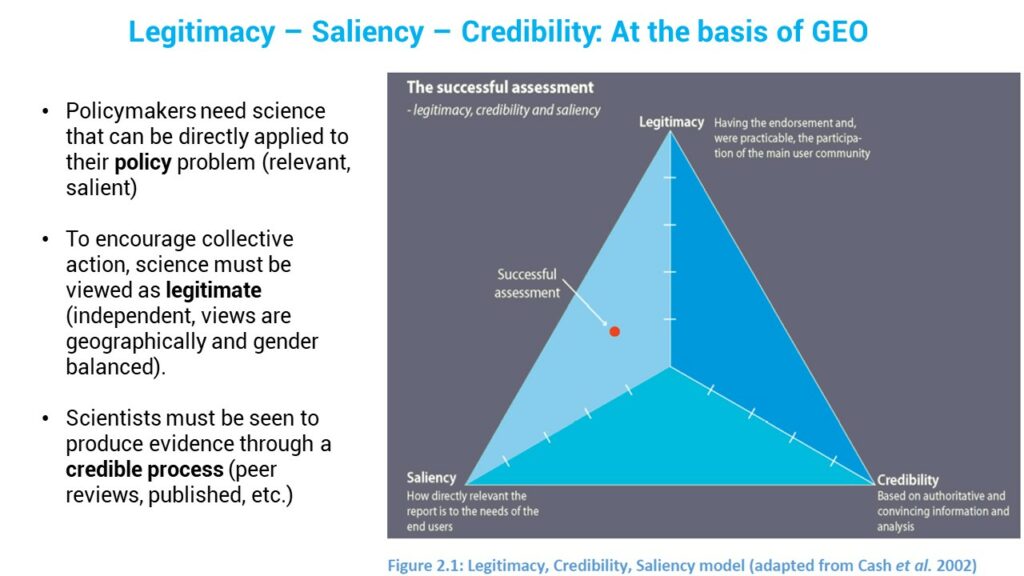

GEO’s main operating principles are that it must be politically legitimate, policy-relevant, and scientifically credible. This means, for example, that GEO underpins UNEP’s decisions in terms of support for major global policy decisions. It is also designed to be flexible and can support policy assessments. This is demonstrated, by the chapters in GEO-6, which were devoted to the assessment of current environmental policy and target-directed strategies in the Outlooks section.

Successful assessment is based on legitimacy, saliency, and credibility. These are also pillars of GEO. In terms of saliency and legitimacy, GEO has a long history of 25 years and is strongly supported by stakeholders. It is a demand-driven process, which aims to produce findings that keep the target user in focus, always ensuring that the findings are useful and presented in a language that can be taken up by the audience. In terms of credibility, this is supported by a rigorous scientific process based on a number of aspects, but especially the robustness of the review process and balance in terms of expertise, gender, and geography of all the drafting teams.

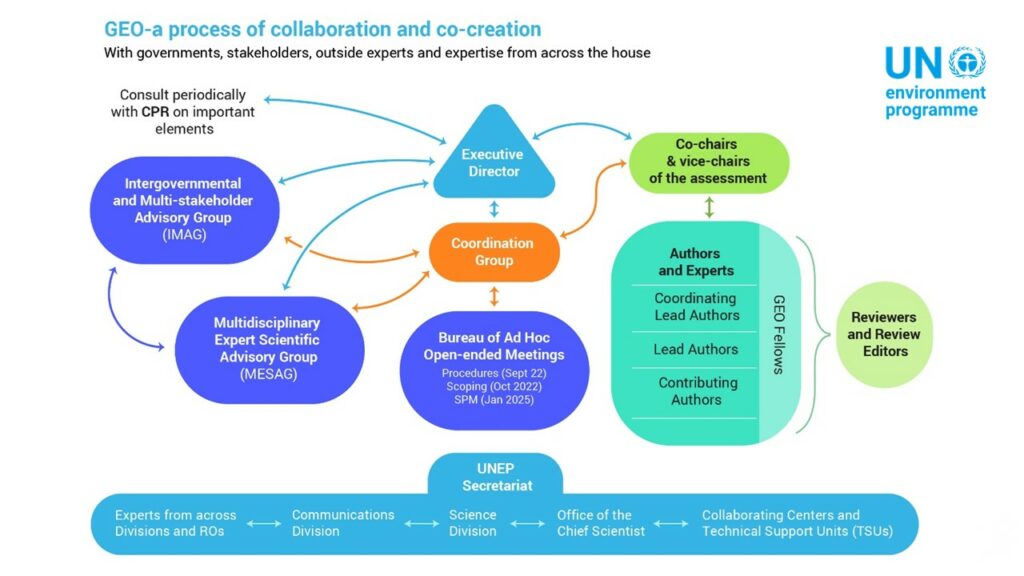

One of the key strengths of GEO is that it builds on a large group of diverse and multidisciplinary experts external to UNEP. At the center of this process is the Executive Director. On the left-hand side, you can see the two main advisory bodies that support the Executive Director: the Intergovernmental and Multi-Stakeholder Advisory Group and the Multidisciplinary Expert Scientific Advisory Group. You can see in the graph how both advisory groups are perfectly balanced in relation to their connection with the Executive Director and the connection between themselves. This is how GEO’s scientific credibility and policy relevance are supported and ensured. On the right-hand side of the graph, we can see the experts, the authors, and the drafting teams who are supported and coordinated by the co-chairs and vice-chairs of the assessment. All of this is supported by a group of experts from UNEP’s Secretariat and from the Office of the Executive Director.

The GEO-7 procedure document was approved in September 2022 during an ad-hoc open-ended meeting, which included experts, member states, and representatives from stakeholder groups. The procedures document contains the operating principles. It discusses the consistency and comparability across GEOs, how to ensure the relevance of the findings, the legitimacy as a demand-driven process, and the balance in the teams in terms of expertise, gender, and geography to ensure credibility. The document also goes a bit further to provide clarifications on more specific issues such as definitions, terminology, clearance processes, governance structures, and other details related to running the process.

In terms of scientific credibility of the assessment, which is one of the operating principles and guiding principles, it is developed further as procedural guidance in the procedures document. It specifies, for example, the review process, which is based on existing best practices from other assessments. Additionally, it defines the number of review rounds, how they are conducted, how the authors are engaged in the review process, the role of review editors, and the interaction between reviewers and authors. This is the level of detail that the procedural guidance provides, and this helps the MESAC ensure the scientific credibility of the process.

Hala RAZIAN | OiC Head of Secretariat, International Resource Panel

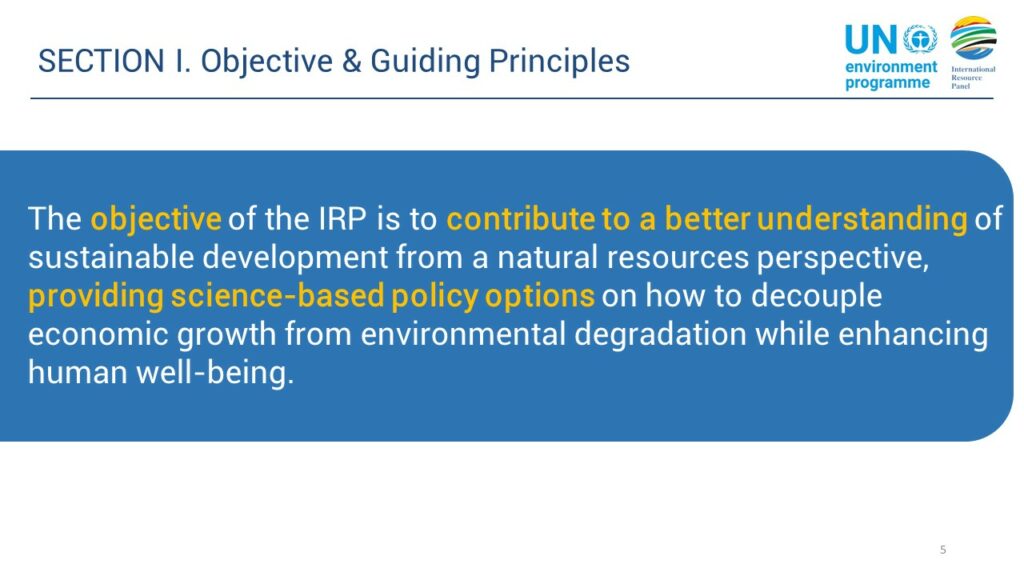

We perform the same science-policy function as the IPCC and IPBES, except for two key differences. We focus on resources, and we don’t fit directly into a Convention.

- Focusing on resources means fossil fuels, metals, minerals, biomass, and water, and how these items are used, produced, and consumed in the global economy. What the impact of that process is on people and the planet, and with the help of our steering committee, we try to identify policy-relevant recommendations to change the way resources are used in the global economy for the benefit of people and the planet. We focus on resources because their use has been growing at an alarming rate, and their impact affects biodiversity and climate in ways that are fundamental.

- We do not feed directly into a convention but rather aim to bring the science of the IRP about resources to the relevant intergovernmental bodies, including the UNFCCC, the CBD, the HLPF, and others.

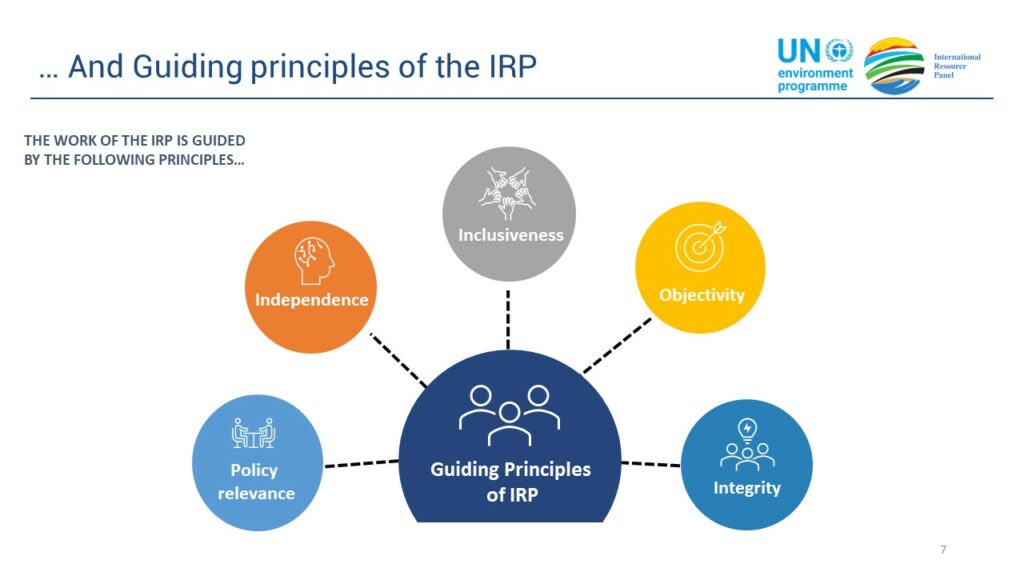

Policies and Procedures | Our policies and procedures document was adopted in 2016 by our steering committee and this document kind of guides all that we do. The steering committee has the approval authority over any amendments, while the secretariat is responsible for the day-to-day operationalization of those principles.

Objectives and guiding principles | Our guiding principles are already integrated into our objectives. I will touch on each of those quite quickly and give a couple of examples of how they’re operationalized.

- Policy relevance: Regarding the operationalization, in practice is safeguarded mainly by our steering committee. They are the body has approving power over our program of work. They request new study topics and approve requests from other members. When it comes to our actual scientific products, they are an integral part of the review process, where they look at whether the scientists are presenting things of policy relevance and provide input and recommendations to those products. So, policy relevance really drives the role of our steering committee.

- Independence: Here, we rely heavily on our panel members to secure our independence. Our panel members are nominated by a group of expert reviewers, an independent group, to serve for a term of four years, renewable up to a maximum of two terms. They are not remunerated, they work for us pro bono, and they do not represent any organization or country. They work in their individual capacity, and these terms of panel membership help to ensure our independence. One of the key strengths of the IRP is that the final approval to publish any scientific study rests in the hands of our panel’s scientific members. They approve work to go to peer review, and they approve work for final publication. Another way we have ensured our independence through our policies is in the way our funding structure works, whereby private funding can never exceed the amount of money we receive from public funds, and that’s one way that we ensure our integrity and independence.

- Inclusiveness: It is one of the most important of our guiding principles, but also has been one of the most difficult to put into practice for us because these principles were put in place in 2016, several years after our panel had already been active and producing work and recruiting members, both from the scientific and steering committee side. So, when this principle of inclusiveness was put in place, we were already starting, unfortunately, at a bit of a disbalance where we had many of our scientists who were men from the Global North, and our steering committee membership mainly reflected the Global North. But we have been working to really improve that balance moving forward. There are some ways that diversification is reflected in our policies. So, in terms of whether you are required to financially contribute to the panel if you’re a steering committee member from the OECD states or not. Panel scientists, although they work pro bono, we do cover certain expenses that they may incur in the process of their work, and our panel co-chairs are split between a developed and developing country, and often also along the lines of gender. However, this is still a work in progress for us, and here I think is a great opportunity for this new science-policy panel to start on the right footing, perhaps, by suggesting already quotas that you may wish to follow in nominating your scientists or otherwise, which is an approach that the IRP has considered in the past.

- Objectivity: We undertake an expert review in which our scientists have the final approval of our work.

- Integrity: IRP is one of the few to explicitly reference conflict of interest disclosures as part of the mandate for our scientists, and we also draw on the support of the Inter-Academy Council in case there is any scientific dispute that we are unable to resolve through the normal functioning of our panel to support us.

Eduardo BRONDIZIO | Co-Chair, Global Assessment, Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

These slides outline our eleven operating principles. I want to contextualize them and talk a little about how they play out in an assessment.

IPBES has 140 country members, it was formed in 2012 after several years of negotiations of drafts, and I think that’s an important part of how the guiding principles developed. IPBES was very much already building on the work of the Convention of Biological Diversity, which has, since the early 90’s, developed a convention that also aimed to be inclusive and representative of all the aspects related to biodiversity research. So many of the things that are part of the guiding principles of IPBES benefited from twenty years of development within the CBD and later the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. This includes, for instance, the inclusion of indigenous and local knowledge, representation from different regions and different stakeholders, knowledge systems as part of the assessment, and so forth. So, it was a process that led to negotiations and then four years of negotiations among countries in which countries of the global South had a very strong voice in developing this resource. So when they were formalized in 2012, they were largely shared by those members of the platform, all the experts and stakeholders that participated in that process. That aspect of having a shared understanding and a shared commitment to those principles made all the difference in the way that they became operationalized. Each operating principle had a contribution to the global assessment.

The first aspect that played an important role was in the scoping process of an assessment. Scoping is a very central process to set an assessment on the right footing, and those principles start to play out in those assessments. For instance, how do you bring together different teams to represent the principles and values that are here, considering international processes that have already done work that overlaps with an assessment, the interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary nature of the team, seeking balance in gender, region, indigenous people, and local communities? All of that was key to the scoping process that already reflected different voices and different perspectives, but also set the questions that would follow the principles and points and values in the guiding principles. Starting from the scoping process, we see the guiding principles provide a common platform and a shared understanding of the values and priorities for the platform.

The second aspect that plays a key role is operationalization of an assessment. Assessments, like the Global Assessment and other ipbes assessments, are by nature aimed at being inclusive. This is key when you form the assessment team. You’re looking for people who are representative of the elements that we see in the principles. The preparation of the team for an assessment itself reflects part of the assessment. It also reflects the challenges that we face when we have principles. For instance, it is very hard to achieve and find the balance that would be ideal for an assessment as defined by the principles, but, we are in a process of improving towards meeting that goal. Setting those principles actually forces us to really look hard to bring a team that represents what we want in terms of diversity, inclusion, expertise, and so forth.

The other aspect that is really important to realize some of those principles is that you have the conceptual tools that are understood by those participating in an assessment and, of course, by all involved in an assessment process that provides support for us to take those principles forward. Ipbes has a conceptual framework that defines how the platform sees the relationship between nature’s contributions to people, and human well-being. This relationship is what we use as a framework to look at the different analyses that we do. It’s not only having the principles but having a shared understanding of them and having the conceptual tools that allow you to operationalize them and to recognize them. For instance, the conceptual framework recognizes that there are different knowledge systems, worldviews, and ways of thinking about nature, nature’s contributions, and human well-being. That is part of the conceptual framework, that is recognized in the framework that has been approved by the entire Plenary. It offers a shared vision and a shared understanding in which each expert can see themselves contributing to a particular area, but as part of a larger picture, and also understanding that there are complementary knowledges and approaches to any given aspect of the conceptual framework and of the assessments that we do. So, those shared tools, like a conceptual framework and analytical tools, translate those guiding principles into operational principles that we can use on a day-to-day basis and mediate bridges for discussions among experts that may have come from different fields.

Another important part of operating principles is the inclusivity of knowledge systems, in ipbes. It is particularly innovative by including not only peer-reviewed research but also a broader array of scientific literature, for instance, in reports and considering indigenous and local knowledge. Therefore, developing approaches to bring those together, to complement each other, and to make an assessment stronger.

The third aspect in which the guiding principles play a key role, is in the process of drafting and negotiating an assessment. In crafting different chapters and tackling the questions of the scoping document, those principles give authors both the responsibility and the concern with making sure that when you go back and prepare a chapter for an assessment, you are considering those different principles. Respect for different disciplines, respect for different knowledge systems becomes part of the process of developing and drafting an assessment.

We have, in order to fulfill these principles and achieve those goals, you end up being very proactive in planning consultations and collaborations throughout the process and making sure that you have a transparent and participatory process where you hear, you listen, you share, and learn from a co-production process from all sorts of stakeholders. Member states participate in interest groups, and that reflects then on the writing of the assessment and how we translate that into a language that is policy-relevant, inclusive, reflects different understandings, but also represents a shared document of the platform.

When you have principles like ours, those are always a work in progress. Many of those principles are aspirations that we do not necessarily have the conditions to fulfil yet. Therefore, they depend on a continuous process. An example of this is inclusion. That’s an important priority. IPBES has been exemplary in making every aspect of its work program inclusive, but it remains a work in progress. It’s always a process of identifying more collaborators from different regions, having a strong capacity-building program that brings a new generation to contribute and share the values reflected in those principles. Increasing representation is always a work in progress, improving the analytical tools and the mechanisms in which we operationalize those principles into an assessment are also a work always in progress.

The guiding principles provide an umbrella and a roadmap that really brings the diverse set of authors together in the process of assessing the Global Assessment.

Q&A

Q: We know NGOs do a lot in terms of awareness, advocacy, and capacity building. So, what roles do NGOs play in effectiveness?

Ko BARRETT | They, of course, play an important role in helping to facilitate climate solutions around the world. In the case of the IPCC, several NGOs are observers to our process. As such, they participate in our approval sessions for the reports. This is an important perspective to bring into the diversity of perspectives that we try to represent in our science. I could have also mentioned the important role of indigenous organizations and indigenous knowledge in our reports.

Q: Are there operating principles that any of you wish could be part of the third panel’s current principles, but they are not there yet?

Ko BARRETT | I think we probably all have a principle like this. In the case of the IPCC, I believe it needs to be strengthened. That is the encouragement to member governments to really consider diversity when they are nominating people to the leadership team for the IPCC, and also scientists to our assessment processes. We don’t have a mandate for gender equity. We don’t have a mandate for trying to find balance between Global South and Global North scientists. However, we really need to strengthen our procedures with regard to increasing the diversity of our participants. The science shows, and the research confirms, that bringing in a multitude of perspectives only strengthens our assessments. For that reason, I would say, strengthened procedures to encourage a stronger balance would be helpful.

Eduardo BRONDIZIO | We do have this mandate in our principles, so we do purposely look for that. I agree, the governments could do a better job in offering a broader range of representation in their nominations. I don’t feel any particular gap within our principles, but perhaps one that comes to mind is the participation of governments in reviewing documents and assessments. Sometimes, during some cycles of review, we have very limited participation of governments in the review process. There are some governments that tend to really dedicate a lot of effort to that. However, in some cycles, the participation is way below the desirable. So, a principle that commits governments to be very involved during the whole process could be helpful as well.

Hala RAZIAN | What I appreciate from the GEO process, for example, is their use of GEO fellows as a way to uplift and engage youth or scientists from different regions that might not have the opportunity. What’s missing from the IRP is maybe this principle of engagement, or bringing everyone along, or an active way of lifting up scientists from contexts which are not as advantaged as the Global North, for example.

Mar VIANA | Hala Razian, in your introductory presentation, I liked from the IRP that it encourages innovation, especially from the point of view of communication of the findings. The GEO is already working on digitalization and finding ways to maximize the impact, but I think this is something that should be even more enhanced. Perhaps encouraging innovation in regard to how to communicate the findings and how to engage different types of communities, from stakeholders to the general public, to make the findings and the actions proposed by these assessments effective.

Q: Could you comment on the boundary between policy-relevant and policy-prescriptive advice?

Ko BARRETT | This is such an important principle for the IPCC, I think the boundary has actually shifted for us over time, although it’s always a firm line that we have never cross. We’ve gone so far as to evaluate the feasibility of certain policy options, something that policymakers have asked of us. They ask, what is the science or on whether these things are working. That’s policy relevant, but of course we don’t say, “Is this policy working in X country?” which would be, I think, going over a line certainly for IPCC. We need to maintain our unbiased approach to the science.

Hala RAZIAN | For the IRP, one way we approach this, of course we are not policy prescriptive, but we try to magnify our policy relevance by looking at our findings through a regional lens, dividing our findings based on the different income groupings that countries may find themselves in. There is no one-size-fits-all recommendation that we could give in any case. Every country is different in context and capacity. For us, the way we increase our relevance is by trying as far as possible to address the wide range of options that could be available to countries rather than prescribing a single modality.

Q: Hala RAZIAN, can you expand on the usefulness of including a conflict-of-interest policy or process? For the others speaker, could it be desirable to have it in this panel or in the context of the work that you are doing?

Hala RAZIAN | In terms of a conflict-of-interest disclosure requirement, this has been quite useful where, for example, in undertaking peer review or excusing themselves from certain functions, our panel members have informed us that there might be a potential conflict. This only serves to strengthen our scientific rigor. As far as I have been with the panel, we have never had cause to use our conflict resolution mechanism that is stipulated in our procedures. We rely on consensus and open discussion and dialogue. It’s nice to know that we have this option, however, in practice, it has not been something that we have had to draw on.

Mar VIANA | As far as I know in the GEO, maybe this is not described as an operating principle, but the members of the different bodies need to disclose or sign a conflict-of-interest form. We have procedural guidance regarding, for example, in the scientific advisory panel, if there’s a conflict for a member of the panel group who wishes to become an author. There’s a conflict there, and we have mechanisms to move from one group of participants, like a drafting team, to the advisory bodies or the other way around, if this happens. So, the mechanisms are in place within the GEO.

Q: How do you overcome problems when politics or government positions on an issue interfere with the science-based consensus reaching?

Eduardo BRONDIZIO | Depends on at what stage of the process you’re talking about. When it’s part of a review process that is open and disclosed, you’ll see the kind of input and it becomes part of the discussion and negotiation and involves more people. I think this is a healthy part of the process, because countries bring their perspective, but in a process that is transparent.

It’s much more challenging when you get to a negotiating phase, where you have documents you’re negotiating, and then you have political perspectives playing out in the findings of the document. It becomes much more complicated, and it has to be dealt with both at the expert level and at the political level. There’s no way of separating the two when you are in a plenary. That’s a symptom when there isn’t enough participation during the development because when there is very healthy participation during different stages of preparing a document, many of those differences become negotiated, become clear, are tackled upfront. The hard part is when those things come at the very last hand when you are kind of negotiating things.

We had experiences negotiating, for instance, categorizing countries in terms of using a system like the World Bank’s levels of income versus a UN system in terms of developing and less developed countries. That’s an interesting case where we had to redo the analysis based on different categories and show in which way those different categories would influence the results. Then we had to find a middle ground in which we would go forward, because we brought the experts and the political negotiation together. However, a good process should avoid this sort of surprise when you are at the later stage of an assessment.

Ko BARRETT | From an IPCC perspective, Eduardo’s comments really resonate. However, we always have a negotiation of our summaries word for word, by countries, and the words matter to them. Often the suggestions that we get from countries are helpful to help us move away from scientific jargon to more understandable findings that an average person could understand and act on. But in our case, the science always has the final word, so countries will certainly negotiate the wording, but we always defer to scientists to make sure that the end product of a negotiation of our words still retains its scientific integrity.

Q: Is that written? Is that part of a practice? How do you do it? Because one big challenge that we might face is the dilution of the scientific evidence to get into the negotiated text and the minimum common denominator. So how is that? Is it a question of being included somehow, or is it a question of how things have evolved historically and the power, and I will use the words that you were saying, of the science?

Ko BARRETT | I’m not sure it’s written in our case. I don’t think it would be possible to write that in a way that was actionable. Certainly, over time, this reliance on the science as the final arbiter has evolved to be a keyway of doing our business. Now, that doesn’t mean that sometimes our scientific findings don’t end up in our final assessment. Sometimes it’s just impossible to find wording that satisfies the countries, but it’s rare honestly. I’m just a strong believer in the consensus process and having everyone feel that the end product represents something that everyone can support. Listening to countries is important because these words end up as assessments supporting a whole negotiating process in the framework convention. So, the words really matter to countries and having a consensus far outweighs anything that may actually be potentially lost or diluted in our end report.

Q: What is one thing that your group started to do, but realized was a bad idea and changed over the years?

Hala RAZIAN | This is a practice that has evolved a little bit with our policies and procedures. We used to only officially have full scientific assessments as the product that the IRP produces, and we were finding it very difficult to juggle ad hoc requests that might come in from different members or developing things on a shorter turnaround time to feed into specific forums on demand with that rigid format of full scientific assessments. So while we were developing our policies and procedures, we explicitly outlined the different types of products that the IRP produces and different modalities of their approval and production process for each one, depending on how extensive the research is. We have specific modalities for scientific assessments that should be completed within one year, which is a short turnaround, and which are led by our co-chairs for example, and each one has a different level of external review and approval. That’s something that we took based on our experiences previously operating with only full assessments as our outputs.

Q: Are there any relevant principles or practices to safeguard commercially sensitive information in any panel? Anything that needs to be inserted or included in operating principles towards this aspect?

Eduardo BRONDIZIO | An important element of our approach is to be inclusive of indigenous knowledge systems and to be sensitive to the sensitivity of such knowledge. So in addition to the general principles that we’re talking about, there are also specific set of principles for working with indigenous and local knowledge, and with knowledge holders. These are equally important because they set the boundaries of how to follow ethical procedures, free and prior informed consent, and evaluate what kind of knowledge you should or should not include in an assessment. That’s a fundamental part of the platform, to have a clear set of principles for working with particular knowledge systems.

Q: Eduardo, could you shed some light on how you’re addressing the capacity building aspects in the IPBES?

Eduardo BRONDIZIO | I would divide it into a few parts. Building capacity involves everybody. When your part of the process, you bring multidisciplinary teams and representatives from different sectors, and increasingly representatives of indigenous peoples. Capacity building involves everyone; it’s being open to learning and respecting other kinds of knowledge, working within a common framework, and learning together how our particular piece of expertise fits within a larger framework that is guiding an assessment. There’s that larger capacity building aspect, which is part of the spirit, we expect that experts and others who join an assessment are ready to be part of. It’s a collective learning process that enhances a shared understanding of why we’re doing this.

The second part of capacity building is bringing a new generation to gain experience. One of the very successful aspects of the IPS is the fellows program. This program selects fellows who represent the principles of international representation, gender balance, expertise balance, and so forth. These fellows are put from the beginning of an assessment to work with the assessment team, and they’re distributed across chapters, but they also form their own group. In my experience, we had a group with a dozen to fifteen fellows in the global assessment. It was one of the bright spots of the assessment. They were central to the chapters, but also, they took a much bigger experience out of it.

The third part of capacity building is to continue to enhance the functions of the program and some of the principles. So for instance, there is an effort to create a network of social science and humanities to bring more people from that community to participate in the environmental assessment. That’s not a trivial task and it involves a lot of social scientists who are used to working independently of natural scientists and others. This parallel process of creating networks, having conversations, learning the common lexicon, the common way of thinking, and challenging those too, that’s also part of capacity building. So, I think about capacity in a very broad way as something that involves everyone in the assessment process.

Ko BARRETT | We also have begun to use chapter scientists and are looking specifically to bring in scientists from the Global South. In the past, when we’ve had a convening lead author from a developed country, they would bring in someone who works at their university, and we were finding an inequity in the number of chapter scientists and support scientists that we were having. A real focus on bringing in these scientists from the Global South is helping our processes. In the case of the IPCC, we won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2007 and started a scholarship fund to produce Ph.D. scientists from the Global South. Now we have a pipeline of folks that we can bring in who have been supported through our scholarship fund to play the role of chapter scientist.

Closing Remarks

Gudi ALKEMADE | Chair, OEWG | Deputy Permanent Representative to UN Environment Programme, Netherlands

I think the questions in particular helped raise a bit more understanding and maybe also some of the challenges and the evolutions that were made in the different panels. I thought it was a very informative conversation. I appreciated the presentations. This is a good basis for member states and stakeholders to start thinking about what should be captured when we guide or when we make a proposal on operating principles as an outcome of our process.

Documents

Links

- Operating Principles: Learning from Previous Practice | Background document to support discussions on operating principles

- Roadmap towards OEWG 2 | OEWG Secretariat

- Ad hoc open-ended working group on a science-policy panel on chemicals, waste and pollution prevention | UNEP

- Road to OEWG 2 | Science-Policy Panel to Contribute Further to the Sound Management of Chemicals and Waste and to Prevent Pollution / SPP-CWP Webinar Series

- Developing a Global Science-Policy Panel on Chemicals, Waste and Pollution Prevention