Événement Virtuel

Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues | Plastics, Climate and Air Pollution

The Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues aim to facilitate further engagement and discussion among the stakeholders in International Geneva and beyond. In addition, they intend to address the plastic crisis and support coordinated approaches that can lead to more efficient decision making.

About the Dialogues

The world is facing a plastic crisis, the status quo is not an option. Plastic pollution is a serious issue of global concern which requires an urgent and international response involving all relevant actors at different levels. Many initiatives, projects and governance responses and options have been developed to tackle this major environmental problem, but we are still unable to cope with the amount of plastic we generate. In addition, there is a lack of coordination which can better lead to a more effective and efficient response.

Various actors in Geneva are engaged in rethinking the way we manufacture, use, trade and manage plastics. The Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues aim to create synergies among these actors, highlighting efforts made by intergovernmental organizations, governments, businesses, the scientific community, civil society and individuals in the hope of informing and fostering stronger cooperation and coordinated actions. The dialogues will also look at what the different stakeholders have achieved at all levels, present the latest research and governance options.

In addition, although the dialogues target stakeholders from all continents, they aim to encourage increased engagement of the Geneva community in the run-up to various global environmental negotiations, such as:

- UNEA-5 (1st and 2nd sessions) in February 2021 and February 2022

- BRS COPs in July 2021

- SAICM ICCM5 in 2022

This first session of dialogues will end in February 2021 to build momentum towards the first session of UNEA-5. It will aim to facilitate further engagement and discussions among the International Geneva stakeholders and actors across the regions and support coordinated approaches that can lead to more efficient global decision making. It will also intend to provide a platform to further carry the discussion from the recently conclude Ad Hoc Open-Ended Expert Group (AHEG) on Marine Litter and Microplastics towards UNEA-5 part 2 in 2022.

The Plastics, Climate and Air Pollution session is the second dialogue to be organized leading to and making recommendations towards the High-Level Dialogue on Plastic Governance Dialogue on 11 March 2021.

The dialogues are organized in collaboration with the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions Secretariat, the Center for International Environmental Law, the Global Governance Centre at the Graduate Institute, Norway, and Switzerland.

Plastics, Climate and Air Pollution Session

While we are familiar with the presence and impact of plastic on oceans and the freshwater ecosystem, the plastic crisis is multifaceted and deeply connected to other aspects of the ongoing environmental crisis. For example, the plastics sector is one of the main industrial contributors to climate change and air pollution. This session looked specifically at the contribution of the plastic life cycle to climate change and air pollution, including assessing the gaps and possible options to address these challenges at the global level.

In 2019, the production and incineration of plastics added more than 850 million metric tons of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, equal to the pollution from 189 new 500-megawatt coal-fired power plants. This data was according to the report Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet published by CIEL in May 2019 and was presented at this session. The rapid global growth of the plastic industry, largely fueled by natural gas, undermines efforts to reduce carbon pollution and prevent a climate catastrophe. In addition, it destroys the environment and endangers human health.

The burning of plastics also releases toxic gases such as dioxins, furans, mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls into the atmosphere and poses a threat to the environment. Microplastics have been detected in the atmosphere of urban, suburban, and even in remote areas such as in high-altitude glaciers, the Arctic and Antarctic suggesting potential long-distance atmospheric transport for microplastics. Leading academics in the detection of microplastics in the environment and the environmental flows of both microplastics and toxics provided an update on the current state of information in this area.

Member States from diverse regions shared their challenges and experiences while experts discussed governance options to reach agreed emission targets and limit pollution.

Other Sessions

- Plastics and Waste | 26 November 2020

- Plastics and Human Rights | 14 January 2021

- Plastics and Health | 21 January 2021

- Plastics and Standards | 28 January 2021

- Plastics and Trade | 4 February 2021

- Plastics in the Life Cycle/SCP | 11 February 2021

- High-Level Dialogue on Plastic Governance | 11 March 2021

Speakers

H.E. Amb. Miriam SHEARMAN

Deputy Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission of the United Kingdom to the United Nations and other international organizations

Anare LEWENIQILA

Deputy Permanent Representative of the Republic of Fiji to the United Nations in Geneva

Steven FEIT

Senior Attorney, Climate and Energy Program, CIEL

Steve ALLEN

Microplastics Researcher, University of Strathclyde

Deonie ALLEN

Research Fellow, University of Strathclyde

Helena MOLIN VALDES

Head, Climate and Clean Air Coalition Secretariat, UNEP

Jan DUSIK (moderator)

Lead Specialist, Sustainable Development, WWF Arctic Programme

Summary

Welcome and Introduction

This second session of the Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues focuses on climate and air pollution, and is taking place a few days before the virtual Climate Ambition Summit co-hosted by the United Nations, the United Kingdom and France, in partnership with Chile and Italy. This virtual Summit will mark the fifth anniversary of the adoption of the Paris Agreement.

In the past days, ambitious commitments toward reducing net emissions have been announced by various member states and the private sector. Through today’s discussion we should learn more about the links between the plastics and the climate crisis.

Welcome | Jan DUSIK, WWF Arctic Programme

The specific purpose of this plastics dialogue is to look at climate and air. If we take all the three topics plastic climate and air, and if we portray it to the year 2020, which is exceptional and difficult for everybody, we can see that there are clear linkages to all these three environmental features.

Enhanced Ambition to Fight Climate Change and Air Pollution, and Address the Plastics Crisis | H.E. Amb. SHEARMAN

The Geneva beat plastic pollution dialogues is a brilliant initiative. Not only is it a priority policy area for the United Kingdom, but it is also an issue I care about deeply on a personal level. We should learn a lot today about this important issue for our planet.

The United Kingdom is hosting COP26 next year. During its presidency, the United Kingdom focus is going to be on encouraging countries to commit to ambitions NDCs and long-term strategies for net-zero emissions, ideally before the summit in Glasgow, next November.

To keep up momentum, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson is hosting on 12 December a virtual Climate Commission Summit in partnership with Chile, COP-25 presidency, and Italy, COP- 26 partner. This will coincide with the 5th anniversary of the Paris Agreement. The summit will be an important moment to drive forward collective action, as we move towards COP-26. It will be an opportunity for leaders to bring forward new commitments that put us firmly on a greener more resilient and sustainable path.

In fact, you might have seen that the UK announced a new NDC last week. We are now aiming for at least a 68% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by the end of the decade, compared to 1990 levels.

Of course, we understand that not all countries will come forward with new NDCS or net zero commitments immediately. We recognize that many developing countries, in particular, have been impacted, and plans subsequently delayed by COVID-19.

We are also keenly aware of the fact that appetite for new planet finance commitments has dipped, as countries struggle with the economic impact of the pandemic. We know that public finance will need to become a key 2021 presidency priority.

As countries make their commitments, it is really important to recognize that tacking climate change is multifaceted: The plastic crisis, air pollution and climate change are closely related.

Enhanced Ambition to Fight Climate Change and Air Pollution, and Address the Plastics Crisis | H.E. Anare LEWENIQILA

At the outset, from a small island developing state perspective, there is no better time for enhanced ambition to fight climate change than the time that we’re living in today. We can also see that COVID-19 has given us a head start in the race towards zero in terms of emissions reduction and also on air quality. The race towards zero emissions requires everyone’s contribution, whereas United Nations or as individuals.

The Fiji mission is working on two important threads of work. One is the 2050Today initiative by the swiss government, which is focused on reducing our carbon footprint in Geneva. This is a small initiative, but it reflects enhanced ambition towards fighting climate change. In doing so we are demonstrating that we are contributing to the much larger picture of what the world is trying to pursue today.

A second is this very important topic of addressing plastic pollution, which we all know is the greatest threat to sustainable development. The work on plastics is important, because it is also intricately linked to climate change and oceans. The ocean is part of our way of life and working on reducing plastics and marine litter in the ocean is central to the conversation that we are having.

Plastics also exacerbate climate change disruptions. For example, plastic bags can block drains, exacerbating flooding, it also effects our coral reefs which undermines climate stressed ecosystems, which are important for local economies and people who depend on it.

Fiji, in the ambit of the committee on trade on the environment of the WTO, together with China, is trying to grow the conversation around addressing sustainable plastics trade and how we work with the international actors in the fight on addressing plastics pollution. Right now, we are putting together the foundation or the building blocks for coherent relations among these international community of practice of international actors, to ensure that we have a complementarity in our efforts on reducing plastic pollution. Finally, this is also another important step towards the much bigger conversation on circular economy, which is also a great conversation that we’re having right now. By starting with the discussion on plastics, particularly on the aspect of trade, we can also contribute to that much larger discussion in the near future, which is very important in the work that we do in trying to achieve environment sustainability.

Setting the Scene | Plastics, Climate and Air Pollution

Plastics and Climate | Steven FEIT, CIEL

In 2017, CIEL released the briefing “Fueling Plastics – How Fracked Gas, Cheap Oil, and Unburnable Coal are Driving the Plastics Boom”. The ultimate takeaway is that the US fracking boom has made natural gas really cheap, and that is driving a massive expansion in new infrastructure for plastics and petrochemicals in the United States. This is also happening in Asia and because of shipped gas and gas liquids from the United States, this is also starting to happen in Europe. The reason for this is because plastic is fossil fuel in another form.

99% of plastics are derived from fossil fuel feedstocks, from oil or gas, or occasionally and rarely coal. This is not an accident or a coincidence this is actually the plan. Petrochemicals are expected to be the largest driver of global oil demand growth from now through 2040, outpacing its use in transportation, industry, in power, or in buildings.

Against the backdrop of this massive expansion in petrochemical and plastic production, CIEL along with a number of other organizations released in 2019 the report “Plastic & Health: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet” that outlined the human health impacts of the plastic life cycle. Later in 2019, CIEL released a report « Plastic and Climate« , which talks about the climate impact across the plastic lifecycle and that’s what I’m here to talk about today.

If you take nothing else from this presentation, take this:

- Greenhouse gases are emitted at each stage of the plastic lifecycle

- Plastic pollution is a significant and growing threat to the earth’s climate

- Stopping the expansion of petrochemical and plastic production and keeping fossil fuels in the ground is a critical element in addressing the climate crisis.

The plastic lifecycle can be divided into essentially four buckets.

- Fossil fuel extraction and transportation

- Production and manufacturing of plastic

- Disposal of plastic waste

- Ongoing environmental impact of plastic

Extraction and transport of fossil fuels for plastic production produces significant greenhouse gases. There are emissions from methane leakage and flaring, and venting, from the fuel combustion in the energy usage in the process of drilling for oil or gas itself, and then often ignored, emissions from land disturbance when forests and fields are cleared for well pads or pipelines or other extractive activities.

But by far the most emissions intense process in the plastics lifecycle is the production and manufacture of plastics. There’s the cracking of alkanes into olefins with you know making the molecules ready to be turned into plastic, the polymerization and plasticization of olefins into plastic resins, and then all the other chemical refining processes to make the additives, the plasticizers, the dyes, everything that goes into what you ultimately recognize as plastic. This is an extraordinarily energy and emissions intense process. In addition to requiring large inputs of electricity or heat, it also has a large emissions profile of direct greenhouse gas emissions.

Once plastic is used and disposed of it is either landfilled, recycled, or incinerated, if it is not lost to the environment. Of particular concern from a climate perspective, is incineration because plastic is fossil fuel in another form, so burning plastic is burning fossil fuels.

Our friends at Gaia constructed as of scenarios. The worst case scenario, the industrial outlook where plastic production continues to increase, and incineration as a method of managing plastic waste increases in it’s importance. By the year 2050 we could see over 300 million metric tons of net emissions of greenhouse gases just from burning plastic packaging alone. When you put all of that together, we estimate that last year the entire plastic lifecycle emitted at least at least 0.86 gigatons of greenhouse gas CO2 equivalents, which is equal to 189 coal plants running 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. If these trends continue, by the year 2030 we could be talking about emissions equivalent to almost 300 coal plants, and by 2050 emissions equivalent to over 600 coal plants. At these levels greenhouse gas emissions from the plastic life cycle could eat up 10 to 13% of the global carbon budget needed to keep global temperature rise below 1.5°, which makes tackling the plastics crisis a fundamental and inextricable part of tackling the climate crisis.

Emissions from the Plastic Lifecycle

Plastic in the oceans may also interfere with the oceans capacity to absorb and sequester carbon dioxide. The oceans have absorbed about 30% of all anthropogenic carbon admitted since the dawn of the industrial era. It has done this in part using the biological carbon pump. Phytoplankton at the surface ocean, similar to plants, uptake carbon when they produce food via photosynthesis. Those phytoplankton are eaten by zooplankton and then through either excretion or respiration and death, small particles sink down into the deep oceans moving that carbon from the surface down into the deep and making some room for more carbon to be absorbed from the atmosphere. There is evidence that microplastic particles in the ocean are interfering with the development and reproduction of phytoplankton and zooplankton, which could threaten not just the biological carbon pump but a huge chunk of the base of the marine food web. Although there are differences in where microplastics are distributed in the oceans they are everywhere.

That brings us to high priority actions we can take now:

- end the production and use of single use disposable plastic

- stop the development of new oil gas and petrochemical infrastructure

- foster the transition to zero waste communities and

- implement extended producer responsibility as a critical component of circular economies and

- force and adopt ambitious targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from all sectors and we need to do this while avoiding distractions like pyrolysis and chemical recycling and carbon capture use and storage

To do this it’s worth noting there are currently no efficient global instruments that address the petrochemical origins of plastic. Any instrument trying or claiming to address the plastic crisis as we can see should and must ensure that it includes measures along the whole life cycle, to effectively limit plastic production and plastic pollution at the global level. Ultimately, stopping the expansion of petrochemical and plastic production and keeping fossil fuels in the ground provides the surest and most effective path to reducing the rising climate impacts of plastics.

In 2021, we have seen that the tonne has changed. The oil and gas markets have been hit really hard by the crisis and that has affected some of the project level economics and the regional economics of the plastic expansion. We’ve seen the advantage of US production win as oil prices have dropped and oil produced plastic has become more competitive. Ultimately the push for an expansion in plastic production will continue in 2021, the push for additional fossil fuel production will also continue. so on the one hand a lot has changed but on the other hand forces will be pushing to bring us back to that business as usual scenario as soon as they can.

Plastics and Air Pollution | Steve and Deonie ALLEN, University of Strathclyde

Our research is on the transport of airborne micro and nano plastic, mainly remote in areas. It is a very new field of study. When we published our Nature Geoscience paper last year “Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment” showing atmospheric transport of microplastics, it kicked off a flurry of new research of this topic. Our sites are the Pyrenees to the Tibetan Plateau, Mt Everest, the poles and many other places around the world. We also studied the ocean to air exchange of micriplastics showing that the sea breeze can be loaded with Microplastic particles. The bubble ejection from waves breaking, ejects the plastics into the air, the same way as 7 gigatons of sea salt gets ejected every year. A young researcher in Beirut University, Moritz Lehman, is currently working on models of rainfall ejection which may be more applicable to freshwater bodies and it is very promising.

The atmospheric microplastics is a very new field of research that started only about four years ago in Paris, with some research done by Rashid Dris.

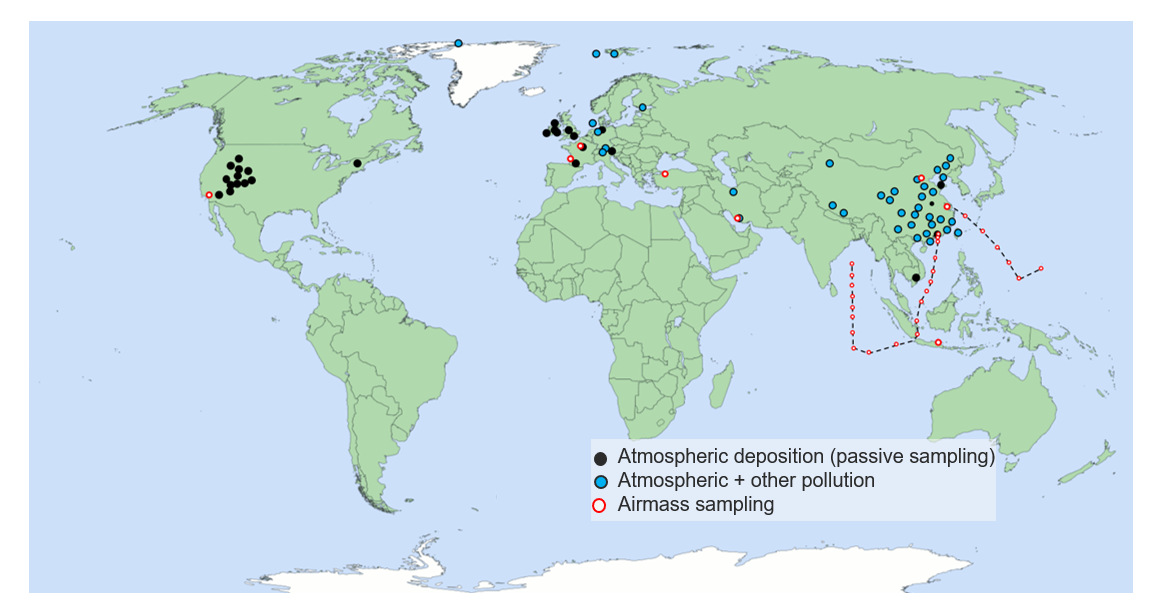

This map illustrates the number of sampling points around the world, not the number of studies. Everywhere we look we find it, but we are not looking in enough places. We need to know how much plastic is in the air, where it’s going, and importantly where it came from, so we might have a hope of slowing it down. We know that the ocean is a source of airborne microplastic and that is going to be hard to mitigate. But there is a potential to stop land-based sources, if we can find them.

Atmospheric micro-plastics studies to date

Cities are considered an obvious source. For example, the air tested in Shanghai and found to contain a staggering 5,700 particles per cubic meter of air. That’s how much plastic is adding to air pollution in cities. That study didn’t look for the very small particles that our research does, but we know that particle counts rise almost exponentially as they get smaller. The average person breaths about 16 cubic meters in 8 hours. That means that we could be breathing in considerable amounts and our work, and that of work by Stephanie Wright and Imperial college London, is showing the respirable PM2.5. size fraction. We now also have the ability to measure nanoplastic through our collaborator Dusan Materic at Utrecht University.

With plastic, it is not just about whats in, it but also whats on it. Many of the toxins we have created stick to plastic; PCBs, heavy metals, mercury, and even some that we would like to forget about like legacy pesticides such as DDT. They all stick to plastic making it a perfect Trojan horse material to carry the chemicals and deposit them inside any animal that eats or breathes it. Many speakers in these dialogues will have described what phthalates are but remember, just because we don’t use BPA in food packaging anymore does not mean you won’t eat it or breath it. We have been disposing of plastic into the environment for decades, and we still don’t know what other chemicals were in it, the list of know chemicals in food packaging alone is over 12000 and 29% don’t have easily accessible toxicity reports. But that is food containers. Everything else is largely unregulated and considered trade secrets. Thousands of forever chemicals like flame retardants are also in plastic. Burning it just releases them. In Indonesia they were using plastic waste as fuel for a tofu plant. This resulted in toxic fallout that created local chicken eggs containing 75 times the acceptable dioxin level. This is just one story. There are many studies showing flame retardants in the air water and biota all over the globe in increasing amounts.

Atmospheric microplastics see no boundaries, these particles travel across countries, continents and oceans.

Atmospheric Microplastic sees no boundaries

On the right is illustrated the microplastic transport from multiple locations to the Tibetean Plateau. On the left are transport models showing annual deposition of brake and tyre wear microplastic across the world resulting from atmospheric transport. With selective sampling we can use these models to point to specific regions as sources.

There is one obvious thing we can see. There are no borders in nature. No matter how clean your backyard is, no matter how perfectly circular you make your plastic economy, you will not be free from airborne micro and nano plastics while there are countries continue to release plastic into the environment. This also means you can’t ship the plastic problem away. The low and middle countries you ship the plastic to, do not have the facilities to deal with it, High income countries don’t even have them. Burning in low temperature fires releases the toxins and microplastic particles into the air. What you threw into the recycling this morning could come back in the air you breath next year after a trip to a recycling station in a low income nation.

All this blowing around in the wind also has other consequences. Airborne plastic has reached the Arctic and Antarctic, even Mount Everest, US national parks. We are not talking about a careless hiker leaving a water bottle behind. Plastics released decades ago can release micro and nano plastics that become airborne, and we have released a lot of plastic since we started making it. That has resulted in airborne plastic reaching the wilderness areas. We are talking 365 microplastics per square meter, per day, in a remote area. Our wilderness areas are our biodiversity reserves. We know that micro and nanoplastics have effects on growth and reproduction for many organisms from soil microbes to plants and on up the food chain. The arrival of plastics into these areas means we could be losing species we don’t even know about yet.

There is a global concern amongst scientists about how much plastic is going into and coming back out of the worlds oceans and lakes. Recently Dr. Steve and Dee Allen co-organized a WMO sponsored workshop, with working groups 38 and 40 of GESAMP. 30 of the worlds top microplastics, oceanographers and atmospheric scientists were invited to discuss the possible significance and impacts of the air sea exchange of micro and nano plastics. It’s unfortunately too early to discuss the findings of the workshop but the report will be a very important document when it is released.

It is worth relating airborne plastic pollution to the SDGs. Airborne plastic impacts a lot of the goals:

- 3. Health. We are only just scratching the surface of the health effects but it is turning up in gut, lung and placental samples. The chemicals are already causing developmental problems in humans. PM 2.5 micro and smaller nano plastics can enter deep into the lung carrying their chemicals. It’s very hard to image a sentence that starts with “The health benefits of breathing microplastics are.

- 5. Gender equality. Women and girls are often workers in recycling plants which likely exposes them to high concentrations of airborne plastic.

- 6. Water security. Airborne plastic can pollute drinking water catchments. How much before water becomes unsafe? Most microplastic scientists feel the WHO report from last year is out of date as new research is coming out every day suggesting cause for concern.

- 10. Reduce inequality. Low income countries should not have to deal with our plastic waste. The prevalence of airborne plastic around ad-hoc recycling centers and illegal dump sites is likely to be many times higher than in high income countries.

- 11. Sustainable cities. Airborne plastic is already adding to air pollution in our cities and urban areas.

- 12. Responsible consumption and production. Plastic is currently a near linear product. That has to change and replacing it with a bio plastic it appears is not the answer.

- 13. Climate change. We know that plastic is a carbon intensive product. It even releases methane when it oxidises. But there are scientists starting to look at whether airborne plastic particles could affect cloud formation, which would have an impact on climate change.

- 14. Conserve our oceans. We don’t know exactly how much plastic is entering the ocean by air yet but the airborne plastic research community think the numbers will be substantial. And it arrives to the ocean in a ready to eat size for many sea creatures like plankton.

- 15. Life on Land. Airborne plastic poses a risk to us, and our ecosystems, no matter how remote it is from humans.

Policy needs to be informed by solid science. Relying on plastic manufacturers to ensure their products are safe and gets recycled is clearly not working. The plastic boom is not consumer driven and it is not consumers that are the problem with waste. The industry needs to be reinvented from the ground up and fast. Recyclability needs to be designed into the product. It has to be easily recycled in the area it is sold.

Single use plastic is the low hanging fruit. Governments are banning bags and straws and it looks like they are doing the right thing, but it is just scratching the surface. Its not tackling global waste management in a meaningful way which is what governments need to do.

The planet has never had as much airborne plastic as we do now, so the effects are unknown. It’s a giant experiment and plastic use and mismanagement is on the rise. There might be a threshold where the damage is irreversible. An amount released into the environment that we can’t re-capture, that eventually becomes airborne. We had better hope we have not already passed it.

Member States Addressing the Plastics, Climate and Air Pollution at International and National Level

Fiji Addressing Plastics, Climate and Air Pollution | Anare LEWENIQILA

From the regional perspective of the Pacific region, a lot of what has been shared is also part of what the region is working on right now.

A recent gap analysis done by the environmental investigation agency and the centre for international environmental law, looked at the landscape of the legal and regulatory framework, the policies and the plans across the whole of the Pacific region and all the countries. Gaps have been identified in relation to what has been shared. Its is important to put words into action, in terms of looking at how we can build on some of the things that science is telling us, and looking at the way forward.

First and foremost, the region is looking at supporting a global and regional banding framework to address plastic pollution as outlined in the Pacific Regional Marine Litter Action Plan. Looking at the discussions that are ongoing in recent forums, there is a call from Pacific states to have an ambitious legally binding agreement rather than voluntary, which could apply at the global, regional and national levels.

In terms of looking at some of the actions, we are already witnessing commitment, with over 70% of the Pacific islands nations, including Fiji, implementing policies to bear single use plastics, and another 25% committed to doing so.

In terms of looking at the regional landscape, we have also identified some potential gaps:

- Look at global and national reduction targets. Setting national targets is something that countries should work on in terms of looking at addressing plastic waste.

- Technology transfer and capacity building. We heard about the need to recycle plastics but for the pacific islands, where the population is spread across vast regions, having a big recycling waste compound would be challenging.

- Control of plastics production. The Pacific islands are very small countries, but in the work that we are doing right now in Geneva, like at the WTO, to start the conversation, with some of the countries engaged in production are actively engaged, looking at finding alternatives to plastic production.

- Design and labeling standards. That is something that we are also trying to look at as a region, to better know what kind of imports we are getting in relation to plastic, and which are the ones that should be considered to be limited.

Phasing out some plastic products in a transition to circular economy, is a growing conversation at WTO now, in terms of looking at the whole life cycle of plastics. But is is just the beginning and it is important we collaborate with member states that are members of WTO, to ensure that this becomes also the work of the WTO to ensure that we can reach some of what needs to be achieved in relation to production.

Some member states rely on these industries for growth, and we need to come together to start the conversation, as these are very important milestones to be achieved in terms of what the science has been saying, and what needs to occur in the WTO and in other important forums.

One of the key findings from the gap analysis is that in the Pacific region we tend to be silent in our approach to addressing plastic pollution.

Now we must not only say coherent as a word, but we need to put that into action. That is what is the greatest challenge that we have. As we have mentioned it is on states to start looking at environment sustainability, the impacts of climate change that we have, as we heard from the experts today, and how to better frame the discussion that we are having have to ensure that we achieve environment sustainability.

UK Addressing Plastics, Climate and Air Pollution | H.E. Amb. SHEARMAN

A major focus of the UK’s policy development is on increasing plastic recycling rates and reducing the amount of virgin material being used to make new plastic, because we know that this will have a positive impact on carbon emissions.

We remain proud of the fact we were the first major economy to put its Net Zero commitment into law.

To help achieve this, we are drafting further legislation to reduce waste and keep resources in the system for longer – leaving behind our traditional linear economic model and creating a more sustainable and efficient circular model from which the environment, the economy and society all benefit.

This will help our society move away from a ‘take, make, use and throw’ approach to resources and materials to a waste less, reuse, recycle and repair one.

There are many other examples of action we’ve taken domestically. For example, we banned the billions of single-use plastics most of us can do without like the plastic straws, stirrers and cotton-buds.

We introduced a charge for single use plastic bags that reduced their sales by over 7 billion per year.

And we introduced a world-leading ban on microbeads in rinse-off personal care products.

We are also shifting the onus from consumers to producers – making sure businesses take full responsibility for the lifetime costs of their products. Businesses of the future will have to think twice before selling a sprig of parsley encased in a brick of plastic.

We have more plans in the pipeline. Subject to consultation, we are looking into the implementation of a deposit return scheme for drinks containers.

And from 2023, we will ensure that collection of household waste is done in a consistent way across the country – including types of plastic collected.

We are also planning for a tax on plastic packaging that contains less than 30% recycled content, with consultations ongoing.

Around the world, we know that people want to see the plastic problem solved. And where we can, we want to support the best efforts.

So we’ve committed £70m to tackling plastic waste through the Commonwealth Clean Ocean Alliance which we lead alongside Vanuatu – and which I’m pleased to say Fiji is also part of.

We’ve also invested £2.6m of UK Aid into the Global Plastic Action Partnership – funding matched by our Canadian friends.

Concerning what comes next, a global agreement to coordinate global action on microplastics and marine litter would be a huge step forward. And I am very pleased to say that – just a few weeks ago – the UK confirmed support for this.

If successful, such a treaty could be akin to the Paris climate agreement or the Montreal protocol to prevent ozone depletion. We urge other countries to support these negotiations and hope that they can begin at the earliest opportunity.

The UK believes that we need to pursue global solutions for tackling the plastic problem – including its impact on emissions and microplastics.

In doing so, we must make sure that alternatives are not actually more harmful than plastic. And it is crucial that we ensure one country’s solution does not have negative impacts on another.

In some cases, we might have to accept that plastic is the best material for the job. Therefore, our domestic and international action should avoid demonising plastic entirely. Instead, we should focus on using it in the best way possible, as well as reusing and recycling it as much as we can.

Finally, we need to keep improving our understanding of the climate costs associated with the production of plastic and share best practice with one another. The UK will keep supporting research in this area, and we are committed to engaging in an open dialogue about this – like we are doing today.

International Governance on Climate and Air Pollution Addressing the Plastics Crisis

Gaps in Air Pollution and Climate Governance | Helena MOLIN VALDES, CCAC

The CCAC was founded in 2012 and includes more than 70 countries across all regions and more than 75 international organizations and NGOs. This voluntary, non-legally binding framework has set out a niche to address a specific set of pollutants: black carbon (BC), methane (CH4), tropospheric ozone (O3), and hydrofluorocarbons (HFC5). This framework promotes integrated solutions to address both air pollution and climate change. Although links with plastics may be unclear, there is certainly a connection and lessons learned from the CCAC governance could be applied in the field of plastics.

The CCAC’s approach is to work at the nexus between climate and air quality, both from the ground up and the top down. Within the ground-up work, the CCAC helps its partners set national goals in this area and empower them to achieve these goals. Within the top-down work, the CCAC holds ministerial and leadership meetings to drive high-level ambition within the existing legally binding frameworks, namely the Paris Agreement and the Montreal Protocol. Part of the work of the Coalition at the ministerial level is to influence these agreements on accounts of scientific evidence and to give them proper relevance to reduce these emissions. The CCAC also works to enhance capacity at the national level in order to catalyse actions that really benefits people’s lives locally. Working peer-to-peer, we drive ambitious action in a few areas and place, showcase what is really possible, disseminate and learn by engaging countries.

This year, the Coalition has adopted a new strategy towards 2030, which goes hand-in-hand with the SDGs and the timeframe set out by the IPCC 1.5°C report, which really makes the case for fast action. As little time remains to avoid the dangerous tipping points in the climate, shortening climate pollutants will help building the fast mitigation trail that can influence temperature avoidance in the short-term, while we work on the long-term CO2 emissions reduction goals. The new strategy is based on three intersecting key directions: (1) drive an ambitious agenda at the highest level, (2) support national and transformative actions in the context of NDCs and others, and finally (3) advance policy relevant research and analysis. In that regard, we look forward to engaging into the issue of plastics and its relation to climate and air.

What we can learn from the CCAC operating way is that partners, including countries and technical partners, can be drivers of change. Working on the ground creates opportunities for multiplication, as each initiative has different leaders in its specific sector who can then influence their own institutions. Some gaps and lessons learned arise from the CCAC’s experience. First, there is still a lack a scientific evidence on the links between plastics and air. While campaigns and awareness about the plastics issue have been very successful so far, we need more scientific evidence to catch up. A second challenge is to maintain high level commitment so that leadership can help setting national and regional targets. Third, multi-stakeholder engagement can be used as an influence, a strategy which has been extremely successful so far in regard to plastics.

Finally, there are discussions around the voluntary versus legally binding agreements. While climate is addressed by the Paris Agreement, there is no legally binding agreement on air pollution at the global level. It could be extremely powerful to structure voluntary schemes, such as the CCAC, because there are much more flexible, nimble and action oriented. Such schemes can be useful complement to the existing legally-binding agreements. Strengthening the UN resolutions from the UNGA or UNEA is also a way to accelerate actions. We need to continue with the campaigns and community engagement to keep awareness high and combine this with some financial instruments. The CCAC has a trust fund, based on voluntary contribution, which has allowed to finance transformative action. For plastics, such a pool of resources to drive ambitions could be useful as well.

Q&A

Collaboration and agreements: How do we explore collaborative efforts that conjoin projects already underway? Why just a global agreement on Marine Plastic – why not the whole value chain – and including soil pollution.

Steve and Dee Allen: As part of the GESAMP workshop this was discussed in detail. There certainly needs to be collaborative efforts for global monitoring. It will take some time to bring the funders into line to support such a network and given the urgency of the problem we hope that organization’s like the UN ,UNEA ,and UNEP can assist with raising the profile of the issue.

Greenhouse gases: Plastic is excellent at trapping heat. Isn’t plastic becoming the new frontier for fossil industries? They are aware that they will have to reduce the GHG emissions burned for our daily activities and hope to be able to keep drilling to produce new the raw material for plastics and also plastics being burned afterwards.

Steve and Dee Allen: This is the basis of Stephan’s presentation but yes, it is well known that fossil fuel industry players are focusing on plastics as a potential market for their products. Fracking is the ideal plastic feedstock as it is much cheaper to produce than offshore oil and gas. Incineration (or energy recovery as it has been labeled) is essentially burning fossil fuels, However it also contains a multitude of chemicals not naturally found in nature. Forever chemicals like PFAs PFOs and the like are highly toxic and do not break down in nature. This is one of the issues surrounding reclaiming plastic to be made back into dielsel fuel. The chemicals do not disappear.

Waste and recycling: Covid waste is encouraging the use of single use plastics. What do you see as solutions to this problem?

Steve and Dee Allen: Covid-19 has been shown to live on plastic between 7 to 18 days. Cardboard and paper only 1 day. So the use of plastic at this time is illogical. Re useable masks and proper hand hygiene are the simplest fixes for the massive rise in covid related plastic pollution. It is essentially and education problem. The confusing advice given early on makes it hard to get the population on the right track. Wearing gloves for example, does not protect you if you then touch your face. A mask is not as helpful if you do not wash your hands.

Answers to questions not addressed during the event

Yin Yin Win (Professor, Taunggyi University, Myanmar): Plastic pollution must be one of the topics in environmental law course and primary education.

Steve and Dee Allen: We agree. A solid understanding of all environmental issues should be primary, secondary and university education. We have only got one planet.

Christopher Faria (Lead Project Manager, International Projects and Consultants, Environmental Division, Canada): Are there any other chemical compositions of plastic that allow better use?

Steve and Dee Allen: The problem with plastic is not the plastic. It can be made with less harmful chemicals and can be recycled (though only a few times). The problem is how we use it and dispose of it. It is currently set up to be a linear economy. Use it and dispose of it. Recycled plastic as a feed stock has little economic value as it is often contaminated with other types. Food grade for example cannot be recycled easily into food grade due to other types of plastic getting mixed in.

Christopher Faria (Lead Project Manager, International Projects and Consultants, Environmental Division, Canada): At the public level, the unaware ideology is “do you really think that my little piece of plastic waste would affect things that much?” In many Latin American countries, where recycling is more cumbersome due to economic restriction, they burn the garbage.

Steve and Dee Allen: There are 7 Billion people saying the same thing. Education is essential to help people realise that this is unacceptable. The plastic you throw on the ground is the plastic your child breathes tomorrow is a good analogy.

Christopher Faria (Lead Project Manager, International Projects and Consultants, Environmental Division, Canada): To what extent does plastic affect ocean acidification?

Steve and Dee Allen: Unfortunately we have no idea on that.

Simone Retif (UNEP International Resource Panel): To Steve Allen, what are your thoughts on impacts of plastic pollution on soil health and flow on Climate impacts?

Steve and Dee Allen: We know that plastic and the associated chemicals have an impact on soil microbes and thus could have far reaching effects though at this stage the research is still new and more work needs to be done to understand it.

Sergio Vallesi (Director Hydro Nexus, Italy): Have you thought that plastic is excellent at trapping heat? Plastic also contributes to global warming not only because of the greenhouse gases produced when the fossil fuel used to produce plastic is extracted but also when plastic is burned. This is the biggest unspoken impact of plastic pollution that leads to local and global heating.

Steve and Dee Allen: The quantities in the air (at the moment) are probably insufficient to trap heat. But if they affect cloud formation as many believe they could then it could have an effect on climate temperatures and rainfall patterns.

Natalia Matic (Principle investigator, Croatian Waters): What and which are the efforts for reducing the carbon footprint connected with a plastics and air pollution?

Steve and Dee Allen: We have not seen efforts to reduce the carbon footprint. As far as we can tell the plastics industry is business as usual with expansion to producing more plastic as the goal.

Najoua Bouraoui (Head of APEDDUB Association Tunisia): When could we transition to ecological and biological plastics?

Steve and Dee Allen: Bio plant based and bidegradable (which can be made from plantl or fossil fuels) have been shown to be as toxic, and often more toxic than standard plastic. So swapping traditional plastics will not help the problem and if it is labeled BIO then people are more likely to let it into the environment. It also needs an industrial compost system with high temps to degrade (PLA). Normal composting does not have the heat and many councils are asking people not to use bio bags for vegetable waste, as the bags just clog the systems. Another problem is if one piece of bioplastic gets into normal recycling it can ruin the whole batch.

Closing

Video

The event was live on Facebook transmissions, and the video is available on this webpage.

Documents

- Invitation

- Presentations made during the event

- Outcomes of the Plastics, Climate and Air Pollution session

Links

The update on Plastics and the Environment provides relevant information and the most recent research, data and articles from the various organizations in international Geneva and other institutions around the world. The Center for International Environmental Law also provides useful resources on the issues of plastic pollution, climate, and health.

Plastics and Climate Change

- How plastics contribute to climate change | Brooke Bauman | Yale Climate Connections | 20 August 2020

- Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet | CIEL | May 2019

- Double trouble: plastics found to emit potent greenhouse gases | UNEP News | 24 August 2018

Plastics and Air Pollution

- Microplastics in glaciers of the Tibetan Plateau: Evidence for the long-range transport of microplastics | Yulan Zhang, Tanguang Gao, et al. | Science of the Total Environment | 1 March 2021

- What are the drivers of microplastic toxicity? Comparing the toxicity of plastic chemicals and particles to Daphnia magna | Lisa Zimmermann, Sarah Göttlich, et al. | Environmental Pollution | December 2020

- Atmospheric transport, a major pathway of microplastics to remote regions | N. Evangeliou, H. Grythe, et al. | Nature Communications | 14 July 2020

- Plastic rain in protected areas of the United States | Janice Brahney, Margaret Hallerud, et al. | Science | 12 June 2020

- Examination of the ocean as a source for atmospheric microplastics | Steve Allen, Deonie Allen, et al. | PLoS ONE | 12 May 2020

- Atmospheric microplastics: A review on current status and perspectives | Yulan Zhang, Shichang Kang, et al. | Earth-Science Reviews | April 2020

- Plastic waste poisons Indonesia’s Food Chain | Jindrich Petrlik, Yuyun Ismawati, et al. | December 2019

- Widespread distribution of PET and PC microplastics in dust in urban China and their estimated human exposure | Chunguang Liu, Jia Li, et al. | Environment International | July 2019

- Simulating human exposure to indoor airborne microplastics using a Breathing Thermal Manikin | Alvise Vianello, Rasmus Lund Jensen, et al. | Scientific Reports | 17 June 2019

- How Does Plastic Cause Air Pollution? | Alice Fortuna | rePurpose | 5 May 2019

- Plastic bag bans can help reduce toxic fumes | UNEP | 2 May 2019

- Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment | Steve Allen, Deonie Allen, et al. | Nature Geoscience | 15 April 2019

- Plastic & Health: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet | CIEL | February 2019

- Production, uses, and fate of all plastics ever made | Roland Geyer, Jenna R. Jambeck, et al. | Science Advances | 12 July 2017

- Inhaled cellulosic and plastic fibers found in human lung tissue | J.L. Pauly, S.J. Stegmeier, et al. | Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention | May 1998