Event Virtual

Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues | Plastics and Standards

The Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues aim to facilitate further engagement and discussion among the stakeholders in International Geneva and beyond. In addition, they intend to address the plastic crisis and support coordinated approaches that can lead to more efficient decision making.

About the Dialogues

The world is facing a plastic crisis, the status quo is not an option. Plastic pollution is a serious issue of global concern which requires an urgent and international response involving all relevant actors at different levels. Many initiatives, projects and governance responses and options have been developed to tackle this major environmental problem, but we are still unable to cope with the amount of plastic we generate. In addition, there is a lack of coordination which can better lead to a more effective and efficient response.

Various actors in Geneva are engaged in rethinking the way we manufacture, use, trade and manage plastics. The Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues aim at outreaching and creating synergies among these actors, highlighting efforts made by intergovernmental organizations and governments, businesses, the scientific community, civil society and individuals in the hope of informing and creating stronger synergies and coordinated actions. The dialogues will also look at what the different stakeholders have achieved at all levels, present the latest research and governance options.

In addition, although the dialogues target stakeholders from all continents, they primarily aim to encourage increased engagement of the Geneva community in the run-up to various global environmental negotiations, such as:

- UNEA-5 (1st and 2nd sessions) in February 2021 and February 2022

- BRS COPs in July 2021

- SAICM ICCM5 in 2022

This first session of dialogues will end in February 2021 to build momentum towards the first session of UNEA-5. It will aim to facilitate further engagement and discussions among the International Geneva stakeholders and actors across the regions and support coordinated approaches that can lead to more efficient global decision making. It will also intend to provide a platform to further carry the discussion from the recently conclude Ad Hoc Open-Ended Expert Group (AHEG) on Marine Litter and Microplastics towards UNEA-5 part 2 in 2022.

The Plastics and Standards session is the fifth dialogue to be organized leading to and making recommendations towards the High-Level Dialogue on Plastic Governance Dialogue on 11 March 2021.

The dialogues are organized in collaboration with the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions Secretariat, the Center for International Environmental Law, the Global Governance Centre at the Graduate Institute, Norway, and Switzerland.

Plastics and Standards

There is growing interest among governments and stakeholders in how standards can support efforts to reduce plastic pollution. Already, a vast array of standards play a role in shaping the plastics economy. In addition to standards on the design and characteristics of plastic products, there are standards on topics as diverse as the chemical composition of plastics and the environmental labeling of products.

National and regional efforts to reduce plastic pollution increasingly refer to the need for stronger and clearer environmental standards for plastics. Calls for a more circular plastics economy, for instance, include proposals for improved standards on issues ranging from recyclability and recycled content of plastics, to the labeling of the plastic footprint of products and toxic additives, the biodegradability and reusability of plastics, and standards for non-plastic substitutes.

At the international level, a number of multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) contain standards relevant to plastics and several proposals for a new UN global plastic pollution treaty emphasise the need for enhanced international cooperation on standards. At the same time, international trade rules include a set of provisions around standards with an eye to ensuring that standards are designed and implemented in ways that are transparent and do not discriminate among countries. In addition, an array of international intellectual property rules also shape the plastics market, regulating matters such as the ownership of trademarks, industrial designs, copyright and patents relevant to conventional and alternative plastics as well as waste management technologies.

Standards can take numerous forms – ranging from standards embodied in government regulations to private voluntary standards, including labels, that emerge from industry or civil society efforts. Across these processes, the opportunities for participation by a diversity of stakeholders vary as does the degree to which governments, industry and the scientific community participate. There are important concerns about the transparency of processes through which standards are developed and the challenges that many businesses, especially in developing countries, face in implementing a proliferating array of standards. At the same time, there are concerns about consumer fatigue in the face of a deluge of product standards and growing skepticism where standards are used to give credibility to products for which the environmental benefits remain contested (e.g., certain ‘bioplastics’ and biodegradable plastics).

In this session, leading experts discussed the relevance of standards to efforts to reduce plastic pollution. Key questions for discussion include:

- What is the landscape of standards relevant to efforts to reduce plastic pollution? What efforts are underway to develop new standards that could help tackle plastic pollution and what is missing?

- Which are the key national, regional and global actors? What are some of the key private initiatives?

- How best can governments cooperate internationally on standards to reduce plastic pollution? What could be done bilaterally or regionally through stronger harmonization or mutual recognition of environmental standards? What are the respective roles of international initiatives like the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA), and the World Trade Organization, the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions and Strategic Approach to International Chemicals Management (SAICM)?

- How are intellectual property rules and standards relevant to the challenges of reducing plastics pollution?

- How much confidence should we have in standards as a central part of the solution to plastics pollution? How can we ensure that decision-making on standards is informed by environmental expertise? How great are the risks of consumer fatigue and cynicism in the face of an ever-growing array of environmental labels – and how can these be addressed?

- What are the limitations of standards in terms of timeframes for development and implementation? How can governments address business concerns about the costs of compliance with a proliferating array of public and private standards, and especially the challenges faced by developing country businesses?

Other Sessions

- Plastics and Waste | 26 November

- Plastics and Climate and Air Pollution | 10 December 2020

- Plastics and Human Rights | 14 January 2021

- Plastics and Health | 21 January 2021

- Plastics and Trade | 4 February 2021

- Plastics in the Life Cycle/SCP | 11 February 2021

- High-Level Dialogue on Plastic Governance | 11 March 2021

Speakers

Reinhard WEISSINGER

Former Senior Expert, Research and Education, ISO Central Secretariat

Karen RAUBENHEIMER

Lecturer, Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS), University of Wollongong

Justin WILKES

Executive Director, ECOS

Feng WANG

Coordinator, Circularity and Waste, Consumption and Production Unit, United Nations Environment Programme

Anja VON DER ROPP

Senior Program Coordinator, Climate Change and Food Security, World Intellectual Property Organization

Carolyn DEERE BIRKBECK

Senior Researcher, Global Governance Centre, The Graduate Institute (moderator)

The participation of the Global Governance Centre in this collaborative series was made possible through support from the Swiss Network of International Studies (SNIS).

Summary

Welcome and Introduction

Introduction to the Session | Carolyn DEERE BIRKBECK, Global Governance Centre

The recent years have witnessed a growing interest among governments and stakeholders in how standards can support efforts to reduce plastic pollution. There is already a vast array of standards that play a role in shaping the plastics economy, and today we look at what role they could play in helping us to reduce plastic pollution.

At the regional and national level, discussions are arising about the need for stronger and clearer environmental standards for plastics. In the EU context, there are discussions on the role of improved standards as one way of helping promote a more circular plastic economy. At the international level, multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs) already contain various types of standards referring to plastics, and there are several proposals, for instance for a new UN global plastic pollution treaty, that also emphasize the need for more international cooperation on standards.

The word “standards” itself is used in different ways by different people in these discussions. People may be referring to regulations or to voluntary standards; there is a lot to do in terms of unpacking that language. The experts at this session will guide us through this topic to understand the relevance of standards to address plastic pollution, as well as the challenges, limitations and opportunities that come with it.

Setting the Scene

Mapping the Status of the Plastics and Standards Landscape: Institutions, Processes, Gaps, and Opportunities | Reinhard WEISSINGER

In order to understand the role of standards with regards to plastics, we first need to have a basic definition of standards. Standards are typically voluntary instruments that address products, processes, systems, services, etc. In that sense, they are different from regulations which are compulsory instruments. They are developed by consensus between different stakeholders, based on the consolidated results of science, technology, and experience. The purpose of standards is to provide, for common and repeated use, rules, guidelines or characteristics for activities or their results. Under certain circumstances, standards can become part of or support regulations, when the latter incorporate or reference standards.

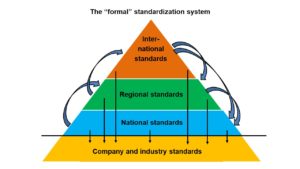

The formal standardization system is structured like a pyramid, with national, regional and international levels who each have their standards and standardization organizations. At the base, companies and industries can develop their own standards or adopt those of the higher levels. While standards are often adopted from higher levels to lower levels, this influence can also go the other way around when lower-level standards are inputs for the development of higher-level standards.

Standardization organizations are multiple, and this landscape may look confusing. There are national, regional and international standards bodies – some of the international ones belonging to the UN system. Standards organizations outside of the formal system, including various NGOs working on voluntary sustainability standards – are also present and their number has increased since the 1980s.

Standards are instruments to generate societal, economic, and/or environmental impacts. At the start, knowledge creation and new opportunities from innovation kick off consensus building activities, as they are introduced into the standardization process. Through these activities, stakeholders from different groups – academics, civil society actors, governmental bodies, businesses – come together to develop a standard. By being published by a standardization organization, this knowledge is disseminated through society and the economy, and leads to standards implementation. The implementation then generates impacts. Some standards require verification of compliance through conformity assessment.

Many standards exist in relation to plastics. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) have around 700 and 500 standards on plastics respectively, with another 180 projects underway. ASTM International – formerly known as the American Society for Testing and Materials – already established a committee on plastics in 1937. And these are only a few among the many organizations that provide standards on plastics.

While these various organizations have long focused on traditional aspects of plastics, specific committees and working groups have now been established to develop standards on the environmental aspects of plastics. These include standards on testing methods for determining degradability in various environment, disintegration of plastics over time, carbon and environmental footprint, recycling and waste management. Many standards are developed specifically on bio-based plastics related to test methods, biodegradability, etc. The CEN committee on bio-based products also developed standards on horizontal aspects – sustainability criteria, life cycle analysis, certification and related issues that apply to all types of bio-based products, including plastics.

Generally speaking, what needs to be done is adopting a holistic view of the plastics value chain, including the raw materials, production processes, use, sorting, and end-of-life. We need to address plastic pollution from the perspective of design. In the past, design focused on functional aspects of plastics, and this has proved to be problematic as issues of pollution has not been given enough attention. By addressing the problem upstream, we can reduce leakages all along the value chain.

Recommendations for standardization include: (1) develop standards with a systemic, whole value chain approach that considers re-use and end-of-life aspects, (2) undertake mappings to identify any equivalence between standards developed by different standards bodies, (3) develop taxonomies of plastics and of their quality-levels to ensure the quality of secondary raw materials, (4) ensure material transparency to facilitate recycling processes, (5) reduce the use of different types of plastics and avoid mixtures which are hard to recycle, (6) develop simple and clear labeling systems, and (7) systematically address plastics leakages into the environment throughout the value chain.

The voluntary nature of standards is a clear impediment to their ability to address plastic pollution. In order to scale up the impacts of standards to combat plastics pollution, they need to be part of national and international policies.

This requires clear and measurable policy objectives, regulatory measures, incentive systems, financial support and training and educational programs. To conclude, standards are an important component of a solution to address plastic pollution, but they are insufficient on their own. They need support through policies, financing and regulations: combined, they can become very powerful.

Standards and a New Global Agreement to Prevent Plastic Pollution | Karen RAUBENHEIMER, ANCORS

Standards are one of the most important thread in working out how to solve the global problem of plastic pollution. They are a key component of a possible new international agreement, as highlighted in the Nordic report. Although standards are not the only tool, they are core to reducing residual waste across the life cycle of plastics, thereby reducing the possibility of leakage into the environment, as well as greenhouse gas emissions and other impacts. If used properly at the national level, standards can also improve the livelihoods of many vulnerable communities.

This presentation provides an overview of the objectives of a new legally binding agreement and the mechanisms to use global standards to achieve the reduction of plastic pollution across the life cycle and the global value chain. Previous speakers presented the technical processes through which standards are developed. In this presentation, I will shed light on the political processes to make these standards operational across the value chain.

Instead of expecting local governments and the sorting and recycling industry to manage the increasing amount of plastic waste, we should be tackling the problem from the design phase. Standards can be very helpful in this approach. The framework agreement sets out to achieve this and the dialogue today emphasizes the need for a legally binding agreement. The proposed design of the agreement uses global standards as a central tool for countries to regulate and manage the products placed on their market. When a product doesn’t meet the standards, a country can ban it or place higher taxes on it or insist on some form of extended producer responsibility (EPR) scheme.

The agreement would not be a trade agreement, although it would influence trade internationally. While it is particularly important for those countries who do not have domestic manufacturers and only import plastics, it also aims to manage those markets where products are manufactured and consumed in the same country. It should ultimately provide a mechanism to influence the both domestic and international markets.

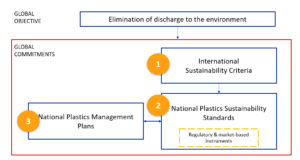

How would a global agreement achieve this goal? The proposed framework has three key operational implementation measures that countries who sign the agreement would agree to undertake. The first has an international focus and the second and third have a national focus. Firstly, countries would agree to participate in the process of designing the global standards, which the report refers to as International Sustainability Criteria. Secondly, Parties would incorporate these standards into National Plastics Sustainability Standards. Thirdly, countries must adopt National Plastics Management Plans, which would map out how countries address the main drivers of plastic pollution across the full life cycle of plastics within their domestic context. Thus, these action plans would also include the National Plastics Sustainability Standards developed under the new agreement. Countries will be given flexibility in a bottom-up approach, but all action plans must work toward achieving the global objectives of the agreement.

Overview of the mechanisms of a possible global legally binding agreement on plastics, as proposed by the Nordic Report

One advantage of having a legally binding agreement is that a finance mechanism can be attached to it. This allows to provide assistance to countries who historically have not had the capacity to participate in processes of developing global standards. Assistance can also be provided for the development of the national standards and action plans.

The hierarchy proposed in the report is that, at the global level, the framework agreement would add broad sustainability criteria. These could be seen as performance criteria that direct the outputs to be achieved and could promote reuse, durability, repairability, recyclability and prevention of leakage. They would be formulated by the parties of the agreement, possibly through open-ended technical working groups. They could also be formulated subsequent to the adoption of the agreement and at various level of details and compulsion. By including this language into the agreement, we can establish the legal base to develop the next level, such as annexes, guidelines, protocols and other implementing instruments, which provide more details. As we more down the hierarchy of standards and the level of details increases, the inclusion of industry and technical experts would increase.

The final level is the National Plastics Sustainability Standards which are operationalized through the regulation of domestic markets, in accordance with the International Sustainability Criteria. National market-based instruments would aim to promote behavior change from both industry and consumers and provide funding mechanisms for waste management services.

All in all, it is important to note that this framework is not a trade agreement, nor a waste management agreement. But it does aim to improve trade through narrowing it down to better designed products and importantly to improve waste management globally. It does so by providing the tools – the global standards – to assist countries to move their waste management services towards an autonomous, self-funding system, and by providing the incentives to collect, reuse, recycle and better design plastic products.

The growing support for standards is a key component to solving the plastic pollution issue. Standards have been mentioned in numerous resolutions by the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA) in relation to marine litter and microplastics, and well as several reports and proposals on a new global agreement. We also presented the approach to industry representation and government leaders, which responded positively. Other institutions, such as the Stockholm convention and SAICM, are looking at options for EPR schemes for chemicals. Most EPR schemes only focus on the financial and physical aspects of waste management, but there are two other components where standards can help: the requirement to better design products, and the requirement to reduce the waste generated along the life cycle.

Standards can also help regional efforts to move to circular economy and sustainable consumption and production (SCP) patterns. They could also fall within the upstream goals under the Basel Convention Partnership on Plastic Waste, to prevent the generation of plastic waste, and improve the collection and recycling, as well as financing thereof.

Challenges, Opportunities and Emerging Issues in the Plastics and Standards Landscape

ECOS and Plastics Standards | Justin WILKES, ECOS

ECOS is an international environmental NGO actively engaging with standards at international, regional and national level. We work across the board at standardization organizations on a range of environmental issues such as climate mitigation and adaptation, sustainable products and materials, and waste. At the international level, ECOS is active in around 30 ISO committees and 60 committees from the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). For issues related to plastics, ECOS is working with ISO, CEN and the British Standards Institution (BSI), and is currently focused its resources on 12 draft standards in preparation.

Before digging into what standards already exist and what is missing to address plastic pollution, let’s remind ourselves that plastic pollution is no accident. Rather plastics are in our environment by design. Standards developed by the market for the market, includes markets that are badly designed. Generally, standards are driven by industry, and to a much lesser extent by policy-makers. Therefore, standards are highly relevant to address the global problem of plastic pollution.

As Reinhard mentioned, there are many standards existing on plastics. At the EU level, CEN has developed a horizontal set of standards on material efficiency that covers plastics. It includes general methods for assessing the recyclability, recoverability, and proportion of recycled material content in energy. Additional standards are currently under development including two sets of standards in support to the EU single-use plastics directive, a method for recycling plastic content, and a measurement method for the unintentional release of microplastics and microfibers. At the national level, the BSI is developing management standards on plastic pellets, flakes, and powders. ECOS is also working on a horizontal standard on microplastics with IEC, and on environmental aspects of plastics from a waste perspective.

The solution to plastic pollution lies in creating systems that do not generate waste in the first place. Unfortunately, industry, standardizers and policymakers currently focus on waste collection and recycling.

Systemic change is needed so that reusable, refillable solutions become the new norm. No standard currently exists in the mainstream standardization world for reusable packaging. Common reusable packaging formats would offer great efficiency gains.

Another large gap and main source of microplastic pollution relates to vehicle tires. We need standards for harmonized test methods for the measurement of tire abrasion, so that it can be included in any labeling scheme and allow consumers to buy more environmentally friendly tires. Another key area for development lies with the definitions of microplastics, which need to be harmonized. For example, ISO and CEN are not aligned in their current discussions, as this constitutes a challenge as they have a similar membership base in Europe.

In terms of contentious issues, the most challenging element is the lack of an ambitious regulatory framework. People are looking at standards organizations for solutions that these organizations are not incentivized to provide or are not in a position to provide. Another fundamental issue is that effective participation and access to information in standardization processes is very difficult for the environmental community and stakeholders from developing countries. It is absolutely vital that standardization organizations are inclusive.

Without an open and transparent approach, international standards have a lower value and usefulness.

A final area to address is the voluntary nature of standards. Standardization is not the goal in itself, but standards are a valuable tool to support legislation and international conventions and agreement. Every effort should be made to ensure that standards are not used to prevent or circumvent legislation. That is a critical issue that we need to keep an eye on.

From a business perspective, we should remember that businesses can avoid costs by innovating. Costs will always be paid by society, and they will be lower when they are internalized. The direction of travel of plastic pollution is clear: sustainability is the order of the day with the internalization of externalities. The winner in that game will be the first mover. This is important because 80% of the environmental impacts of a product are linked with the design phase, and the winners will be those who design the environmental impacts out. Governments have a key role to play here, by disincentivizing bad environmental design and incentivize good environmental design. Finally, international coordination and cooperation, rather than competition, are crucial to address plastic pollution.

UNEP | Plastics Standards Towards a Pollution-Free Planet | Feng WANG, UNEP

The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) engages with standards, eco-labels and consumer information with various of its teams. UNEP provides review of global, regional and national standards on plastics and plastics production, with a focus on different national context and commonalities between standards. A second field of work includes all projects and activities that UNEP carries out to support governments and businesses to develop policy and standards. UNEP also has a team dedicated to developing guidelines on sustainability information by assessing eco-labelling schemes and translating characteristics into customer information. Finally, UNEP compiles case studies for recommendations and best practices and foster knowledge sharing and capacity development.

Standards can play different roles in reducing plastic pollution across the whole plastics life cycle. First, standards provide inform about the quality, safely, health, hazardous content, and chemical concerns of materials and products. They can also help improve and upgrade the quality of material and products by dealing with recyclability, reusability, composability, biodegradability, etc. Standards also support labelling and claims, which are important vehicles to communicate the features of different products.

Standards are particularly important with regards to recycled content in plastic waste streams. As we discuss circular economy, governments want to create a market for secondary materials. Thus, there is a lot of ongoing work to provide norms and standards to improve the quality of the recycled materials so that it can feed back better into the value chain. Apart from dealing with the products themselves, standards can also address the end-of-life and the recovery phase. By providing information on sorting, decontamination and recycling of plastic waste, standards can also help improve efficiency and reduce fragmentation of the recycling process.

Standards present many advantages. They can influence product design, production, consumption and market creation. In that sense, they provide positive impacts by diverting markets toward more circular and sustainable patterns. Standards also ensure fair competition and reduce inconsistencies arising from the wide variety of products and materials.

However, there are also some barriers and gaps to be addressed with regards to standards. First, as standards are made through complex and various processes, terminology is often unharmonized. In practice, standards are proliferous and can vary greatly in how they define quality and other properties. As standards are very technical, the specifications are often made invisible to the consumers, who are then not able to make informed decisions. Standards are often disconnected for real-life scenarios, as the defined scope and methodology is not reflecting the wide variety of possible contexts. In that sense, there is often a mismatch between the envisioned design in standards and the actual end-of-life scenarios.

Actions to move forward and use standards for reducing plastic pollution include: (1) harmonize definition, terminology and criteria, (2) align standards at national, regional and global levels, (3) provide reliable sustainability information and assessment to support standard development, (4) embed actual conditions and real-life scenarios in standard development, and differentiate per sector or context, (5) create better synergies between standards and consumer information, and (6) match the work of standards with enforcement mechanism, market buy-in, consumer behavior, reuse, and state-of-the-art treatment.

WIPO | Plastics and IPs | Anja VON DER ROPP, WIPO

Innovation has a great role to play to help tackle pollution. In addition, many solutions already exist, but we need to accelerate the transfer and adoption of these innovative ideas. Intellectual property is part of the elements that serve to foster innovation as it enables innovators to earn recognition and benefit from what they create, whether it is inventions, research articles, books, designs, symbols, and images used in business.

One of the most important intellectual property rights is patents. These are granted by public authorities for technical inventions. In the fields of plastics, patents can relate to the materials – for example, new chemical compounds that are more easily biodegradable -, packaging designs, or recycling processes.

Trademarks, among which the many different environmental labels, are another important intellectual property instrument. First, there are conventional trademarks, which are protected signs that help a company to distinguish their products from those of the competitors. These are an important means of communication and are increasingly referring to certain environmental characteristics. They can be problematic if they contain misleading information, a process referred to as greenwashing.

Secondly, certification marks, which are often referred to as eco-labels, constitute a specific kind of trademarks. These differ from conventional trademarks in so that they have an independent organization that verifies that products comply with certain standards. Here, the quality of the product depends on the standards and on the verification process.

We know from the telecommunications and consumer electronics industry that there are some cases where standards require patented technology for their implementation. This can constitute a challenge; however, there are currently no such cases in the plastics industry.

From the intellectual property perspective, there is not so much to be done specifically with regard to plastics. However, what we can recommend governments and policymakers to do is to look at the whole range of factors that foster innovation, as the latter will be critical to address pollution. There is a need to create enabling environments, with regards to the quality of institutions, the research infrastructure, market factors, and business sophistication. Standards, and in particular those who make it into regulation, play an important role for such an environment to emerge as they incentivize innovation. It has indeed been observed that, when regulations tighten up, the patenting on technology that allows to comply with those standards is increasing.

As mentioned by previous speakers, terminology and definition are also crucial to allow businesses and consumers to rely on good standards and identify misleading claims in trademarks. Apart from the enabling environment, the diffusion of the knowledge and outputs that have been generated is another area for government action.

In 2013, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) launched WIPO Green, an online platform for technology exchange that contributes to the accelerated adaptation, adoption, and deployment of green technology solutions. It connects those who are looking for solutions and those who offer those solutions. This initiative has seen a wealth of products and technologies dedicated to plastics, such as packaging materials, biodegradable products, bio-based products, products made from recycled sources, and recycling processes.

Q&A

Alexandra Leaton (University of Plymouth): Is there one New Global Agreement to Prevent Plastic Pollution in progress or are there others?

Karen Raubenheimer: For now, there are no negotiations at the international level. There have been various proposals from different groups, but the Nordic report takes a step further by looking at how exactly that could be implemented. To my knowledge, this report is the most detailed proposition. In any case, the hope is that it would be agreed at UNEA5 in 2022 to establish a negotiating committee.

Christopher Faria: Manufacturers have deliberately circumvented process for profitability over years. How do standards get enforced?

Justin Wilkes: Circumventions are indeed an interesting point, because there is no agreed definition and it could refer to a large spectrum of activities. A few references on that matter include a report on circumventions by ECOS, a valuable guide by IEC, and a horizon 2020 project called AntiCCS. Standards remain voluntary instruments, even when markets reference specific standards in the official journal and even when the European Court of Justice said that they do form part of EU law. So there is a lot of work to do to ensure that standards are as robust as possible, so they do encourage companies to follow them.

Reinhard Weissinger: Although the standards remain voluntary, the regulations on which these standards are based or which they are intended to support are requirements that need to be met. Business can use different standards to meet these requirements, but the legal obligation does not disappear. One of the main instruments to enforce the use of standards is market surveillance. In the European Union, there are various instruments of market surveillance and information system to detect products that do not meet standards. However, this is a very complex issues, and there may be some cases where the cheaters are successful.

Closing

Video

In addition to the live WebEx and Facebook transmissions, the video is also available on this webpage.

Documents

Links

The update on Plastics and the Environment provides relevant information and the most recent research, data and articles from the various organizations in international Geneva and other institutions around the world.

- Determining recycled content with the ‘mass balance approach’ – Joint NGO paper | ECOS | 10 February 2021

- Possible elements of a new global agreement to prevent plastic pollution | Karen Raubenheimer, Niko Urho | Nordic Council of Ministers | October 2020

- Upstream Innovation: a guide to packaging solutions | Ellen MacArthur Foundation | 19 November 2020

- Biodegradable Plastics: Standards, Policies, and Impacts | Dr. Layla Filiciotto & Prof. Dr. Gadi Rothenberg | ChemSusChem | 28 October 2020

- Breaking the Plastic Wave: Top Findings for Preventing Plastic Pollution | PEW | 23 July 2020

- Converting Plastic Waste into Fuel | WIPO | 20 April 2020

- Can I Recycle This? A Global Mapping and Assessment of Standards, Labels and Claims on Plastic Packaging | UNEP & Consumers International | 2020

- Policy surrounding Plastic Production | Interview of Carolyn Deere Birkbeck at the Governing Plastic Launch Event | 25 November 2019

- The role of packaging Regulations and Standards in driving the Circular Economy | UNEP | 13 November 2019

- Reuse – Rethinking Packaging | Ellen MacArthur Foundation & New Plastics Economy | 13 June 2019

- Legal Limits on Single-Use Plastics and Microplastics: A Global Review of National Laws and Regulations | UNEP | 5 December 2018

- Winning the Battle against Plastic Pollution with International Standards on World Environment Day | ISO | 5 June 2018

- ISO 17422:2018(en)Plastics — Environmental aspects — General guidelines for their inclusion in standards | ISO | June 2018

- Mapping of global plastics value chain and plastics losses to the environment – with a particular focus on marine environment | UNEP | 2018

- The New Plastics Economy: Catalysing action | WEF & Ellen MacArthur Foundation | January 2017

- The New Plastics Economy – Rethinking the future of plastics | WEF | January 2016

- Bio-plastics: Letting the Planet Breathe | WIPO

- Reswirl: Closing the Loop in Toothbrush Manufacturing | WIPO