Event Virtual

Advancing a Rights-based Approach to Addressing Mercury Contamination | Minamata COP-5 Online Event

11 Oct 2023

16:30–17:30

Venue: Online | Webex

Organization: United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, International Labour Organization, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, United Nations Environment Management Group, United Nations Environment Programme, Special Procedures of the UN Human Rights Council, Geneva Environment Network

This online event to the 5th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Minamata Convention on Mercury was jointly organized by the UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, the UN Environment Programme, the International Labour Organization, UN Economic Commission for Europe, the UN Environment Management Group, and the Geneva Environment Network.

About this Session

In July 2022, the General Assembly adopted a landmark resolution recognizing the human right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment. The resolution, which followed recognition of the right by the Human Rights Council in October 2021 was an unprecedented decision, adopted with unparalleled support (161 votes in favor, no votes against, and eight abstentions).

The adoption of this landmark resolution is an important step toward securing the enjoyment for all people of non-toxic environments in which to live, work, study and play and ensuring inclusive, evidence-based and accountable environmental action.

In June 2022, the International Labour Conference made a historic decision to amend the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work (1998) to include “a safe and healthy working environment” as a fundamental principle and right at work. Nevertheless, millions of workers around the world continue to be exposed to hazardous levels of mercury, highlighting the need for urgent action to address this persistent occupational safety and health (OSH) challenge.

This event explored recent developments in our understanding of the interconnectedness between human rights, occupational safety and health, a just transition and the environment, and identify key entry points to strengthen a human rights-based approach to the implementation of the Minamata Convention on Mercury.

Drawing upon the voices of the UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, key UN partners and activists, the panel shared specific examples of rights-based environmental action targeting emissions and releases of mercury and highlight how States can take more effective action through compliance with their obligations to respect, protect and fulfil human rights to meet their commitment and obligations under the Minamata Convention on Mercury.

Minamata COP-5 Online Events

This session is part of the Online Events of the Fifth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Minamata Convention on Mercury (Minamata COP-5), taking place in Geneva from 30 October to 3 November 2023. Minamata COP-5 Online Events take place during the week of 9 to 13 October 2023. → Find more information on the official website.

Highlights

Speakers

Marcos ORELLANA

UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights

Manal AZZI

Team Lead on Occupational Safety and Health, International Labour Organization

Nino GOKHELASHVILI

Head, Sustainable Development Division, Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture, Georgia

Rochelle DIVER

UN Environmental Treaties Coordinator, International Indian Treaty Council

Julio Ricardo CUSURICHI PALACIOS

President, Federación Nativa del Río Madre de Dios y Afluentes (FENAMAD), Peru

Yuyun ISMAWATI

Senior Advisor and Co-Founder, Nexus for Health, Environment and Development Foundation (Nexus3) | IPEN Steering Committee Member

Griffins OCHIENG

Executive Director, Centre for Environmental Justice and Development | Co-chair, IPEN Toxic Plastic Working Group

Igor GRYSHKO

Human Rights Officer, Environment and Climate Change Team, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) | Moderator

Summary

Igor GRYSHKO | Human Rights Officer, Environment and Climate Change Team, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) | Moderator

- The recognition the Right to a clean, health and sustainable environment by the United Nations General assembly in July 2022 (A/RES/76/300) is an important step to securing the enjoyment for all people of non-toxic environments in which to live, work, study and play and also to ensure inclusive evidence-based and accountable environmental action.

- Conventions such as the Minamata Convention came to exist as a recognition that we must protect human health and the environment from toxic chemicals, and we have enough evidence to establish that mercury is negatively affecting multiple aspects of human life and dignity.

- At Minamata COP-5, member states will discuss several issues that have human rights implications, such as those related to illegal trade in mercury proposals that include skin-lightening products, dental amalgams and product categories associated with fluorescent lamps.

- Discussions will also tackle the use of mercury in artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) and the promotion of environmentally sound and economically viable alternatives; emissions and releases of mercury and its gender implications, among other important issues.

Marcos ORELLANA | UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights

- The thematic report Mercury, small-scale gold mining and human rights – implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes (A/HRC/51/35) prepared and presented at the 51st session of the Human Rights Council offers various insights.

- The small-scale gold mining sector is the largest source of emissions and releases of mercury to the environment by far and it is increasing. While Minamata Convention regulations and controls are working in several areas, when it comes to the largest sector they are not.

- The impacts of small-scale gold mining and mercury use affect disproportionately individuals and groups in vulnerable situations.

-

- Miners, who often live in poverty and are exposed directly to mercury in their efforts to separate the ore from the gold using this metal. Workers are also often working in slavery conditions. It is common to find child workers, and sexual exploitation of girls is common. Miners’ families are often impacted, especially when the separation of the ore takes place in the homes. This impacts women of childbearing age, as mercury is a very important neurotoxin capable of crossing the human placenta, leading to impacts on the unborn child IQ, stunted development, malformations, poor health and so on.

- Indigenous peoples, who live according to their cultural traditions, experience invasion of their lands, violence by illegal miners, exposure to mercury in their food sources. Mercury that finds its way to the rivers and thus contaminates fish upon which indigenous peoples rely for subsistence and cultural practice. The situation of the “Eseja” requires special attention: this group of indigenous people in Bolivia is known as the “people of the river”. Their connection with the river is strong and they rely fully on fish for their sustenance so the contamination of fish by mercury has meant a disproportionate burden and impact. Many observers are beginning to speak about a new Minamata unfolding in the Amazon

3. Shortcomings in the Minamata Convention are contributing to these impacts. Small-scale mining is a use allowed under the Convention and because of that, trade of mercury for small-scale gold mining is also allowed. Another shortcoming is that trade provisions are rather lacking and enable the diversion of legal trade to illegal markets. Annex C to the Convention on small-scale Mercury does not contain a face-out timeline for Mercury use in small-scale mining.

- These shortcomings can be addressed by COP decisions that enable further engagement, such as COP-4 decisions on consultations with indigenous peoples and the design and elaboration of national action plans.

- The report also contains information on how the Convention can be and should be amended to close these gaps and shortcomings.

- Amendments to Article 7 and Annex C regarding small-scale mining so that there is a phase-out timeline in this field;

- Amendments to Article 2 to forbid small-scale gold mining as a use.

- Amendments to Article 3 concerning trade by banning the export of mercury except for sound management of waste where it is allowed; banning imports of mercury from non-parties, strengthening the period or shortening the period in which primary mercury exports are allowed.

- All these measures should be adopted to strengthen a rights-based approach to the implementation of the Convention.

Igor GRYSHKO | Human Rights Officer, Environment and Climate Change Team, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) | Moderator

How can the right to access information, public participation in decision-making making and access to justice be strengthened to inform the implementation of the Minamata Convention on Mercury? How does the Aarhus Convention contribute to increased accountability, public participation and transparency in the negotiations?

Nino GOKHELASHVILI | Head, Sustainable Development Division, Ministry of Environmental Protection and Agriculture, Georgia

- It is critical to ensure procedural human rights – which are stipulated in the three principles of the Aarhus Convention – such as access to information, public participation in decision-making, and access to justice in environmental matters in the context of the implementation of the Minamata Convention on Mercury at domestic, transboundary and international levels.

- The Aarhus Convention is highly relevant in this regard as it provides a legally binding framework on how to implement these procedural rights in practice. The objective of the Aarhus Convention is to guarantee the rights of access to information, public participation in decision-making making and access to justice in environmental matters to contribute to the protection of the right of every person of present and future generations to live in an environmental adequate to health and wellbeing to thrive.

- The Convention and its protocol on pollutant release and transfer registers (PRTRs) set out standards for access to environmental information including those related to chemicals and provide requirements about public participation in decision-making, activities, plans, programs, policies, and legislations for effective access to justice regarding the review of environmental information.

- The Convention imposes legally binding obligations to ensure the protection of environmental defenders for their activities. This is highly relevant to mercury as many cases of persecution and harassment of environmental defenders arise in the context of extractive industries linked to exposure to chemicals such as mercury.

- In June last year, Aarhus parties elected the world’s first Special Rapporteur on environmental defenders as a rapid response mechanism to protect them and to promote capacity building and awareness-raising on this topic.

- Since environmental impacts including chemicals and mercury may extend across country borders, the right under the Aarhus Convention implies its application without discrimination as to citizenship, nationality or domicile.

- Aarhus parties must promote the principles of the Convention in international environmental decision-making and within the framework of international fora in matters relating to the environment, both in the procedures of those processes and in their substantive outcomes.

- There is a close relationship between the Minamata Convention and the protocol on PRTRs which builds on the reporting obligation for mercury and its compound, controls on mercury emissions to air from point sources and releases to land and water, identifies relevant point sources, develops respective inventories and registers.

- The protocol on PRTRs provides for international standards for collecting and making relevant data on pollutants accessible to the public.

- To avoid reporting duplication, PRTRs can serve as a single window reporting platform with easily accessible data to everyone. Currently, over 75 member states are committed to developing PRTRs through either legal or policy obligations, around 50 of which already have working PRTRs systems and are interested in the implementation of an online portal for reporting and public dissemination of pollution-related data. This includes parties to the Aarhus Convention and its protocol, the Escazu agreement, and OECD member states.

- Considering the significance of the treaties, the Aarhus Convention and the protocol are open to accession by any UN member states.

- Georgia ratified the Minamata Convention this year, but it has been a party to the Aarhus Convention since 2001. It is well aware that without consideration of the principles of the Convention, proper environmental protection and sustainable development are not realistic. The principles of the Aarhus Convention should be applied to all environmental activities, especially to MEAs including the Minamata Convention.

- The Aarhus Convention and its protocol have already driven numerous positive changes in legislation practice not only in their parties but also in other member states and processes. They served as a model for instruments in other regions and have a vast potential to assist them. It will be beneficial to apply as needed the Aarhus Conventions and its protocols and procedural requirements for the effective implementation of the Minamata Convention.

Manal AZZI | Team Lead on Occupational Safety and Health, International Labour Organization

- Workers are exposed to this hazard in all these sectors. In gold mining, where the largest use of mercury globally occurs, an estimated 14 to 19 million workers in over 70 countries have to deal with this. They are exposed at all stages of the life cycle of mercury, which includes the production and disposal of mercury-containing products such as thermometers, batteries, dental amalgams and other electronic waste.

- Even small quantities of mercury can cause a range of health impacts for workers that have adverse impacts on their nervous, digestive and immune systems. Some workers may face a double burden of exposure not only to their work, but also to environmental exposures. While mercury can pose negative health effects to all workers, workers in the informal economy; those in micro small medium enterprises and risks; women and pregnant women are high risk; migrant workers who have linguistic barriers in understanding the need to be protected have particular vulnerabilities.

- Over 600,000 children are working in small-scale gold mining and face significant risks to their health, development, physiology, metabolism, and brain functioning.

- At ILO, various projects deal with these working conditions. Supporting workers in certain sectors requires looking at the variety of working conditions, situations and reasons why people’s livelihoods are sometimes linked to these highly hazardous sectors and work and why people accept such jobs.

- We try at least at the global level to move forward with statements and commitments that gather hundreds of countries. The 187 ILO member states came together less than two years ago and announced that the right and principle to a safe and healthy working environment has become fundamental. This has various changes and implications for world trade and working situations around the world, across all sectors.

- The ILO binding conventions that deals with safety and health are No. 155 and Convention No. 187 have requirements and provisions that are now mandatory for every member state to apply whether they have ratified these particular conventions or not.These will have direct implications and potential improvements down the line to the elimination of mercury exposure.

- In line with the Minamata Convention and the ILO Chemicals Convention No. 170, phase-out of mercury use in products and processes should be prioritized and enacted by adopting a use reduction approach, identifying safer alternatives where possible and where available and trying to see safer processes, substances, products where alternatives do not yet exist.

- For the mining sector, formalization is a crucial step toward decent work and addressing mercury use taking place in the informal economy, where 90% of work is conducted.

- Social dialogue is essential because change cannot be enacted without efficient, collaborative and meaningful consultations and dialogue between workers, employers, and governments.

- With the announcement of a safe and healthy working environment as a fundamental principle and right, ILO has proposed a new global strategy on occupational safety and health that prioritizes chemical issues, including a discussion on reviewing its convention 170 on chemicals and potentially adding a global protocol that addresses the new issues facing the world from an environmental and chemical perspective.

- We see some positive sign that will push the current forward in this struggle we are all facing in the issue of mercury.

Igor GRYSHKO

In which ways are indigenous peoples impacted by mercury? With COP-5 approaching, what are your recommendations to ensure the right of indigenous peoples are adequately reflected in the outcomes?

Rochelle DIVER | UN Environmental Treaties Coordinator, International Indian Treaty Council

- Minnesota is a historic mining state where iron, ore and taconite have been mined since the 1950s. We have seen a lot of contamination down the rivers of my people’s nation because of this.

- Mining poses a detrimental threat to ecosystems and waters throughout the Great Lakes region. The Great Lakes area goes all the way out into the ocean, and Northern Minnesota is also house to the head of the Mississippi River, impacting directly Minnesota’s people and beyond.

- Mining waste contains a lot of sulfates, methylmercury and sulfuric acid. This has been polluting the lands and waters, suffocating our traditional food which is mnomen – or wild rice -, and it has been filling fish with mercury.

- Our women have been under fish advisories for at least two decades. Women in rural communities are not always getting the proper information to be able to make informed decisions about their and their babies’ health. The result of this is a generation of babies that are born pre-polluted with mercury.

- We also are victim to coal-fired power plants, their emissions and smoke sacks, which contaminate our land, waters, air and fish.

- Indigenous peoples are more at risk because subsistence lifestyles consume more than 40 times the average fish consumption than other citizens living in the same areas. In our nation, many of our people are hunters, fishers and gatherers, and people, who have more and more often to decide between protecting their health and what aspects of our culture and traditions then will fall to the wayside.

- Dental amalgams are disproportionately used on native people, low-income communities and people of color communities in the United States and Canada. Dental amalgams are on the agenda of Minamata COP-5.

- It is important to realize that when they are talking about what they consider to be safe sources or a safe level of consumption, or exposure, the common approached just take into factor one source and not the cumulative impacts of all of the threats we face daily in our health.

- For Indigenous peoples to have full and effective participation and see some results states must recognize respect and uphold our rights enshrined in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

- During the Minamata Convention INC-5 in 2013, this was not recognized by the states and rights of indigenous peoples were not included in the text nor in the preambular paragraph of the Convention. Our position and participation should be prioritized not just as vulnerable groups but as rights holders, stewards of 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity, and as scientists and knowledge holders we deserve a meaningful seat at the table.

Julio Ricardo CUSURICHI PALACIOS | President, Federación Nativa del Río Madre de Dios y Afluentes (FENAMAD), Peru

- Mercury issues in indigenous territories in the Amazon are mostly associated to illegal mining and bear important impacts on our health.

- Mercury and mining are associated with violence and criminalization for indigenous defenders. During the meeting of Indigenous organizations in Latin America in preparation for Minamata COP-5, key issues identified are related to health and rights. The approach to the problem involves the attention to specific cases that affect peoples and territories but also structural or profound transformations in the models of development that have been promoted in the Amazon. The Convention provides an important mechanism to advance that: national action plans for mining.

- The way forward is putting the rights of indigenous people and collective rights at the forefront and this involves the respect of territorial rights, self-determination, participation and consultation among others. We all agree on the importance of enforcement actions to remove illegal mining that operates within the indigenous territories and also control the traffic of mercury.

- We deem also it is important to adopt an intercultural dialogue, particularly on issues that have to do with health.

- Granting the effective participation of indigenous women as the most vulnerable group especially when pregnant, and the institutionalization of indigenous people within the Convention will allow to get real progress.

- We, indigenous people, protect the territories and are the most affected, therefore more effective participation is necessary.

Yuyun ISMAWATI | Senior Advisor and Co-Founder, Nexus for Health, Environment and Development Foundation (Nexus3) | IPEN Steering Committee Member

- The social determinants of health include gender aspects, lifestyles, people’s work, or the surrounding environment influencing and affecting health.

- In mercury hotspots, exposure pathways through air occur when gold is burnt in houses and the vapor is inhaled by people. These could then continue to affect the surrounding environment through the inadequate disposal of waste byproducts that in turn can impact food sources that will be consumed by the people locally.

- In mercury hotspots, gender inequality is very obvious due to work divisions in artisanal small-scale gold mining. Women and men are exposed to mercury differently, but often women suffer more because they pass on the toxicity in their bodies to their children.

- This map illustrates mercury vapor concentrations in one village, with small red dots indicating locations or houses of people who got sick, and big ones show the high concentration of mercury vapor in the area. Green ones show lower concentrations, however, this standard in the past did not follow the World Health Organization standard because not every country has the same safety standards as the WHO. As a result, these situations lead to pollution that puts the populations at risk of not having access to clean air, clean water, and clean soil for their children to be born with low birth weight and also grow or develop abnormalities.

- Some areas also saw the displacement of people as a result of pollution.

- This form of environmental injustice affects people in rural areas while in the cities where gold is sold, people are not affected.

- As we witnessed Gender inequality and disparities in access to healthcare services and awareness about mercury pollution and poisoning, we decided to establish a program called CHIME – Children’s Health Intervention in a Mercury-Polluted Environment. After a rapid assessment of the status of children, mothers, boys, and girls in the area, we involve children in playing games and developing the map of their areas asking them to describe what their environment looks like, the number of ball mills or gold burners are located in their areas. We also asked them what kind of sickness they experienced, and the children indicated nosebleeds and constant headaches.

- Mothers with children with special needs must be accompanied, assisted and helped because they do not know how to take care of children with disabilities. We conducted capacity-building exercises for mothers and teachers to help them identify symptoms of mercury poisoning.

- Through the project, we also collaborate with health workers to train them to identify poisoning symptoms.

- The project also introduces alternative livelihoods, especially for young people and mothers or women, so they do not get involved with their husband’s jobs or businesses, they are encouraged not to get in touch with mercury directly but use safer alternatives and do other business.

Griffins OCHIENG | Executive Director, Centre for Environmental Justice and Development | Co-chair, IPEN Toxic Plastic Working Group

- Vulnerable populations that are recognized in the Minamata Convention are those who come most into contact with mercury. In terms of the division of labor and different roles, women get exposed to mercury through inhalation from open burning or from the amalgamation that takes place in the mining sites. This represents a violation of the right to a clean and healthy environment.

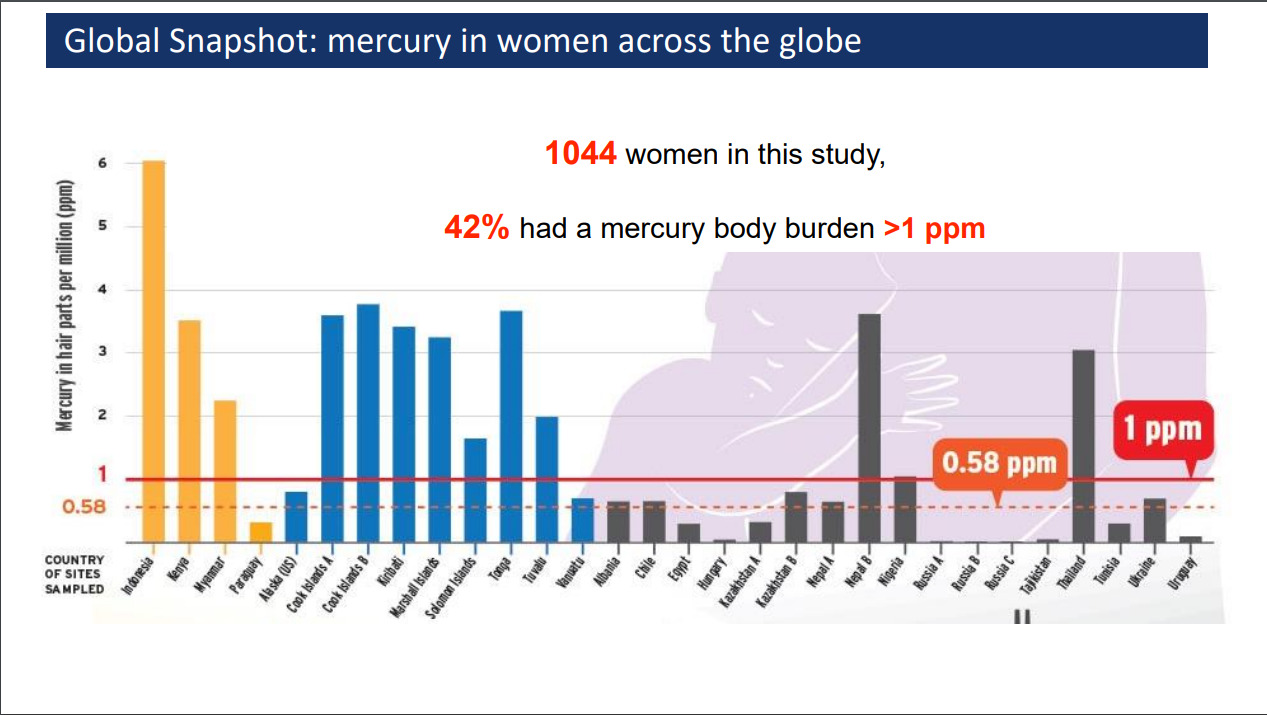

- By conducting biomonitoring studies in partnership with IPEN in 2018, we looked at mercury, sampling air or women of childbearing age and we found evidence of mercury in women, showing how the problem particularly affects the most vulnerable.

- From the studies we grasped the reality of the violations occurring and found that women are implicated with trading mercury or buying gold and openly burning it.

- The health impact is real in the sites: this was a global study that sampled 144, in Kenya we had 31 women that took part, and we provided these results to the women that we sampled it provided a very good lesson on how participation in decision making is critical.

- Providing the information is critical in empowering miners to take charge, to be agents of their change in how to advocate or how to fight for recognition in policymaking decisions. The sector has been largely informal and was considered illegal, so there is no kind of recognition or open policy for miners or communities around mining to participate in policymaking processes. Laws or policies that are made to address this problem likely large the participation involvement of these communities that are largely affected. Their knowledge or their voices are very important to ensure that those policies that are made are effectively implemented.

- Women miners who took part in the Beat Pollution during the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) in 2017 were able to share stories. The aim is to empower them to see how they could form a women’s group to mobilize resources through banking and look at how they can be able to look for alternative livelihoods and protect their health.

- In many cases, miner lack information from the health system and use informal passing of words to describe symptoms. Information is very critical in providing miners with solutions on how to move forward with their lives.

- From studies on the diversion of mercury conducted on material imported into Africa for industrial, we discovered that these are often diverted to the mining site.

- A solution to avoid mercury pollution is closing the tap and looking upstream. We must ensure alternatives are increasing methods for miners to minimize the use of mercury are flourishing. Projects like Planet Gold are an example of that.

- There is a need for balance: minimizing the flow of mercury while bringing in alternatives.

- Self-regulation also represents an issue. While the mining sector is largely informal, it is essential to work both toward formalization and to foster self-regulation among miners. In many African countries, the capacity for the regulatory authorities to implement laws on the ground is lacking. Often, it is miners themselves who should be empowered with knowledge and tools on existing laws to be able to self-regulate. This has been effective in reducing child labor in Kenya, where miners have come together in a mining group through circles or cooperatives to pull resources to ensure that able to also acquire some of these safe mining practices.

Video

Live on Webex