Event Conference

Making Human Rights Central in the Chemicals and Waste Discussions | Geneva Toxic Free Talks

20 Sep 2023

13:15–14:45

Venue: Palais des Nations, Room H.307-1 & Online | Webex

Organization: Special Procedures of the UN Human Rights Council, Earthjustice, Geneva Environment Network

On the sidelines of 54th Session of the Human Rights Council (HRC54), this year’s Toxic Free Talks will take place from 20 to 22 September — three days of conferences and discussions, highlighting the work of the UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights, and of organizations in the struggle for the right to live in a toxic-free environment.

About this Session

Various important international environmental negotiations taking place in 2023 in Geneva and beyond, are addressing chemicals, wastes and pollution, bringing developments in international law on toxic substances and pollution.

The Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions held their last meetings of the Conference of the Parties in Geneva in May 2023. The 5th International Conference on Chemical Management (ICCM 5) will take place in Bonn at the end of September 2023. The 5th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Minamata Convention will take place in November 2023, in Geneva, while the negotiations for a future treaty on plastics will held its third session in Nairobi in November 2023, and the future science-policy platform on toxic substances and pollution will be discussed at a meeting to be held in Jordan, in December 2023. In all these discussions human rights have a central role to play, as the raison d’être of these instruments and institutions is to protect humans and their natural environment.

At this session of this year’s Geneva Toxic Free Talks, panelists discussed steps that have been taken on discussing and integrating human rights into ongoing negotiations, and will explore how these can be further strengthened in ongoing and future discussions.

About the Geneva Toxic Free Talks

The Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights reports every fall to the Council and to the UN General Assembly on issues related to his mandate. The Geneva Toxic Free Talks aim to harness the opportunity of this moment of the year to reflect on the challenges posed by the production, use, and dissemination of toxics and on how Geneva contributes to bringing together the actors working in reversing the toxic tide.

On the sidelines of HRC54, this year’s Toxic Free Talks will take place from 20 to 22 September — three days of conferences and discussions, highlighting the work of the Special Rapporteur and of organizations in the struggle for the right to live in a toxic-free environment.

Speakers

H.E. Amb. Romy TINCOPA

Deputy Permanent Representative of Peru to the United Nations Office and International Organizations in Geneva

Marcos ORELLANA

UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights

David OGDEN

Deputy Executive Secretary (officer-in-charge), Basel, Rotterdam, and Stockholm Conventions

Brenda KOEKKOEK

Programme Management Specialist, Plastic Pollution INC Secretariat

Richard GUTIERREZ

Programme Management Officer, Minamata Convention Secretariat

Therese KARLSSON

Science and Technical Advisor, IPEN

Ana Paula DE SOUZA

Human Rights Officer, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

Diana RIZZOLIO

Coordinator, Geneva Environment Network | Moderator

Summary

Opening

H.E. Amb. Romy TINCOPA | Deputy Permanent Representative of Peru to the United Nations Office and International Organizations in Geneva

- Peru considers the issue of plastic pollution as transversal and cross-cutting, bearing considerable impacts on a wide range of human rights, including the right to life, health, adequate housing, education, and a healthy environment. Its impacts are particularly dire on vulnerable groups such as indigenous and rural women, children, and workers who are exposed to toxic chemicals or air pollution.

- The plastics treaty under negotiations should be firmly rooted in a human rights-based approach that reduces inequality between persons, delivers a just transition and protects the environment, while considering a gender approach.

- Plastic pollution affects women and men differently, also in terms of opportunities, as well as disproportionally affecting developing countries. We need a strong treaty with ambitious goals that consider the needs of developing countries as more concrete provisions.

- The plastic treaty should also include a mechanism to regulate chemicals of concern, for example through a negative and positive approach of listing, chemical simplification, in the form of specific provisions that do not allow and/or eliminate the use of certain chemicals.

- Although evidence and science on the harmful effects of some of the chemicals used in plastics, We also have to consider that we need to continue the need to raise awareness despite growing evidence that the effects of some of the chemicals used in plastic are harmful both to the environment and to humans.

Marcos ORELLANA | UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights

Last year we celebrated 50 years of the Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment and one of the things that came out most prominently was the need for the recognition of the right to a healthy environment.

At the time of the Conference, several voices advocated for the recognition of this right and for the adoption of a human rights-based approach. In the end, the conference declaration contains important elements, but the action plan moved in a different direction and embraced a management approach, which has been inspiring the development of international environmental law at the global level and of comparative law in many countries.

The vision of reducing controlling and minimizing pollution based on the assumption and faith that the carrying capacity of the planet would be able to absorb this without exceeding planetary boundaries is not rooted in reality. The scientific evidence of planetary boundaries on chemicals and waste being exceeded speaks to the profound impacts that this has on the human rights of countless individuals and groups around the world.

Chemicals and waste instruments are the premise of this notion of risk management and reducing and minimizing, means they are out of sync with the current scientific evidence and the imperatives of what needs to be done. Existing instruments are not delivering their full potential, calling for a change in direction, one embracing a human rights-based approach.

Many of the chemicals and waste instruments bear the seeds to this approach. Elements such as in the preambles’ recognitions of the vulnerable situations of indigenous peoples in certain instruments seed access to information. Nevertheless, there is no explicit embracement of a human rights-based approach that would put the right to a healthy environment at the core of what is intended with these instruments, articulate access to information or make a reality the access to remedies.

The resolution that most recently renewed the toxics and human rights mandate, the Human Rights Council guided and requested information on developments gaps and shortcomings in international instruments on chemicals and waste and on that guidance. For example, the parties of the Basel Rotterdam Stockholm Conference including statements, written and otherwise first report General Assembly on Plastics and human rights, also engaging the UNEA to address the gaps in plastic pollution and regulations.

In respect of Minamata produced a report presented to the Council on the largest source of mercury emissions and releases to the environment, which is small-scale gold mining. When it comes to the fifth session of ICCM (International Conference on Chemical Management) the statements and the leadership of my mandate is finally out. So much more could be said about various gaps and shortcomings but the basic point is the pivoting towards embracing a human rights-based approach so that chemicals and waste instruments can be made more effective.

Perspectives in Including Human Rights in Ongoing Chemicals and Waste Negotiations and Discussions

David OGDEN | Deputy Executive Secretary (officer-in-charge), Basel, Rotterdam, and Stockholm Conventions

- Chemicals and waste do not make the headlines but are a silent and ever-looming issue. Their impact on millions requires making human rights central in discussions about chemicals and waste management.

- Chemicals and waste and human rights are far more interconnected than many realize. Chemicals are an indispensable part of modern life but when improperly managed, they pose serious threats to human health and the environment.

- We need a collective and urgent responsibility to ensure our policies and practices respect and uphold human rights.

- Human rights are part of the DNA of the United Nations. Although the words human rights are not explicitly mentioned in the text of the Basel Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions, the implementation of these conventions is intrinsically linked to upholding human rights principles. These Conventions describe a life cycle approach to the management of hazardous chemicals and waste, placing the protection of human health and the environment at the core of their respective mandates by ensuring the chemicals and waste are managed in ways that are transparent equitable, and safeguard human health and the environment.

- These agreements contribute to the realization of human rights on a global scale. Areas where the BRS Conventions contribute to the observance of human rights include:

- The right to life and water safety. Hazardous chemicals and waste can seep into water supplies lead to air pollution and can contaminate food chains, thereby posing serious risks to human life.

- The right to health, as exposure to toxic chemicals can lead to a multitude of health problems from acute poisoning to long-term issues like cancer and birth defects.

- The right to a healthy environment: chemicals and waste pollution can negatively impact individuals and communities right to live in an environment that is conducive to their health and well-being.

- The right to information, since communities are often not informed about hazardous waste that is exposed. Lack of transparency in information denies them the ability to make their own decisions to protect their health.

- For the achievement of these rights, correct mapping of chemicals and where these are found can help governments put in place regulations that would make communities aware and informed.

- Environmental justice is another dimension that links human rights to chemical waste. Improper chemical management often leaves the main brunt on marginalized people, deepening social inequalities and putting the vulnerable at greater health and harm risks.

BRS Conventions Centralization of Human Rights Concerns in their Work

- The BRS Conventions participate in the High Commission for Human Rights Community Practice Group and the Environmental Rights Coordination Group, which hold informal discussions on human rights and the environment.

- The BRS also collaborates with the Office of the High Commission for Human Rights in various areas including organizing side events during the Conference of the parties of the BRS Conventions.

- Regular inputs are provided into their reports and country visits on different issues: the secretary also contributes to regular sessions of the Human Rights Council and other related activities.

Actions BRS Conventions Parties Can Take to Contribute

- Parties can conduct comprehensive human rights impact assessments before implementing chemical policies or waste management plans and must ensure that all legislation and practices are in line with their human rights commitments under international law.

- BRS parties can increase transparency and contribute towards a comprehensive chemical disclosure requirements and labeling so that consumers can make informed decisions and then BRS parties can prioritize community participation and inclusion of local communities in decision-making processes.

- Participatory governance contributes to more effective and sustainable waste management solutions and more generally strengthens multilateral and global cooperation.

- Chemical waste does not respect national boundaries, it can travel through air and water and affect communities long distances from their source.

- Making human rights central to the discussions about chemical management is not optional nor an add-on, it is a necessity. Humanity demands that we tackle these issues to create inclusive, equitable, and sustainable solutions for all.

Brenda KOEKKOEK | Programme Management Specialist, Plastic Pollution INC Secretariat

- The right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment is a key concept and it is fundamental to bring international developments and solutions into the conversation.

- The Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution is working on the development of an international instrument on plastic pollution one of the multiple crises we are faced with. Research shows that humans produce around 430 million tons of plastics per year and without urgent action, that could triple by 2060. Under a business-as-usual scenario, plastics could emit 19% of global greenhouse gas emissions allowed under a 1.5-degree scenario by 2040, and the sheer volume produced and discarded every year is just having negative impacts on ecosystems wildlife, climate, human health, and the economy.

- The zero draft text of the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine

environment, and the synthesis document currently under preparation are the two essential documents that will guide the third session of the negotiation that will take place in Nairobi from 13 – 19 November 2023. Those are based on inputs and submissions by members and observers to the negotiations. These documents already reflect the core spirit of the negotiations, which is delivering an instrument that addresses the full life cycle of plastics by protecting human health and paying special attention to the circumstances of those countries and groups most in need of support. - There is room for human rights concepts to be included in the instruments, building on proposals coming from submissions to include prevention and precautionary principles, intergenerational equity, a right-based approach, the right to a healthy environment, the right to access to information, effective participation and access to justice, and a just transition, especially with a gender perspective and the need for technical and financial assistance particularly for small island developing states and least developed countries.

- Human rights concepts are already included in the provisions of the zero draft, and the protection of human health is firmly based in the proposed objectives. The text already contains provisions on the just transition to ensure waste pickers and vulnerable communities around the world as well as other workers throughout the life cycle plastic have decent jobs and a safe healthy environment. A proposed article on transparency tracking, monitoring, and labeling, could reinforce the right to know and it is particularly important in the chemicals and waste agenda in protecting human health.

- Inclusiveness as an important part of the process. There is a strong level of engagement in the INC process from written submissions to participation in webinars and side events. Observers are constantly engaged in the process before, during and after our sessions. Observers play an important role in building momentum for the INC and bringing forth solutions to tackle plastic pollution. In terms of inclusiveness in this process, there is a space for actors to engage in the implementation of the future instrument through two particular provisions: the promotion of international cooperation and stakeholder engagement. Under stakeholder engagement, there is a proposal in line with the UNEA resolution, to establish an action agenda that promotes inclusive representative and transparent actions, and active and meaningful participation of all relevant stakeholders in the development and implementation of this treaty.

- Engaging with the human rights agenda in these negotiations can support making this is a once in a lifetime opportunity embedded from the outset. Ending plastic pollution is not a job for governments alone so we just want to engage with civil society, women, children and the informal sector, we all are an important part of the solution.

Richard GUTIERREZ | Programme Management Officer, Minamata Convention Secretariat

Human rights are very much integrated in the UN and in the Chemical and Waste Conventions. Article 1 of the Minamata Convention speaks about the protection of human health and the environment from thiogenic sources of mercury and mercury compounds as its main objective. There are various ways in which the Minamata Convention is translating this engagement directly into action.

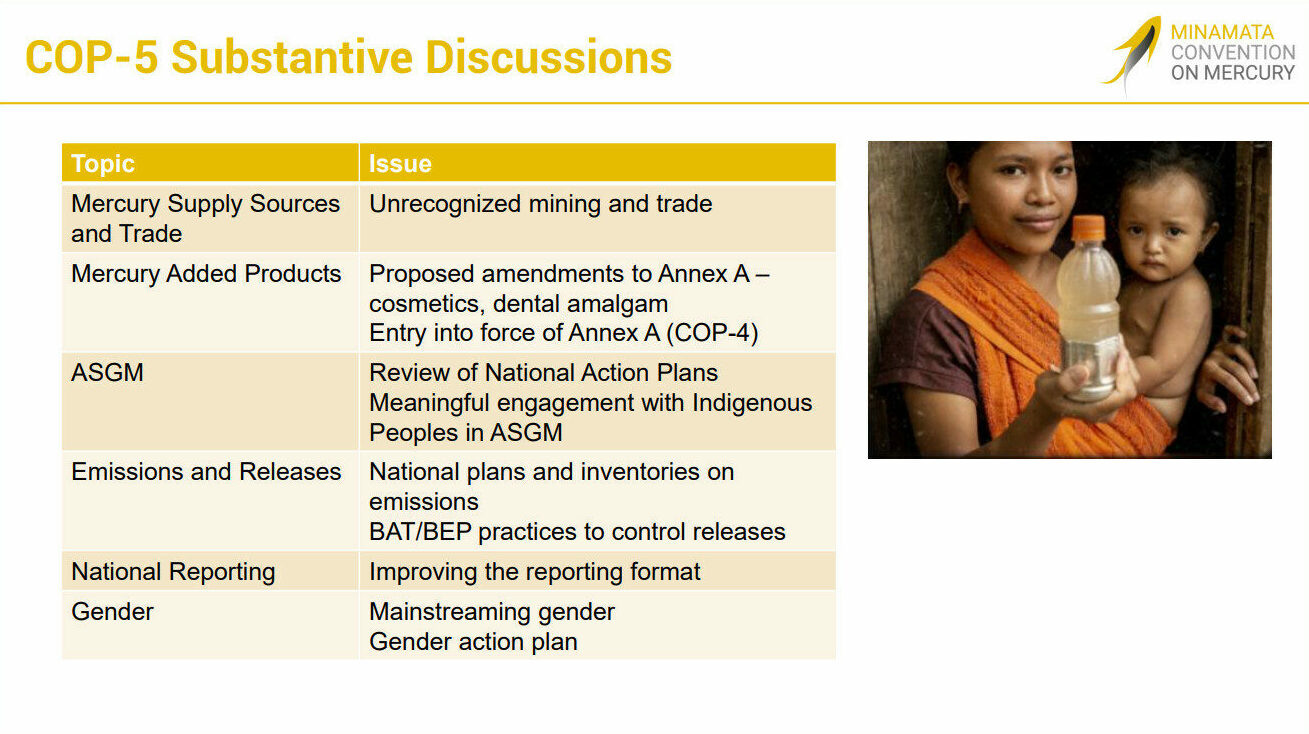

In the upcoming COP-5, substantive discussions will address various substantive issues that have clear human rights implications, and these discussions can help reduce.

In the upcoming COP-5, substantive discussions will address various substantive issues that have clear human rights implications, and these discussions can help reduce.

- Mercury supply sources and trade are some of the key issues identified by parties in the past as these often go unrecognized.

- Mercury-added products do not only require discussions on the management of mercury but also look from a human rights approach perspective to chemicals. During COP-4, parties decided to prohibit the use of dental amalgam for children below the age of 15 and recognized the impacts of mercury-added products on vulnerable populations, especially breastfeeding mothers.

- Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining (ASGM) is the largest emitter of mercury, and it will be critically addressed at the upcoming COP-5 through the review of the National Action Plans. A review mechanism must be established and this is an important instrument in which integrating a human rights approach will allowstakeholders to better include them.

- Emissions and releases, looking at the national action plan and inventories, and most importantly the best technologies available, and best environmental practices to control emissions are going to be discussed.

- National reporting. We are working towards improving the national reporting to improve information and most importantly to make it available to the public. There are still issues to overcome for example confidential use, but parties are willing and we are working to overcome obstacles in order to make information available in every key aspect of the work that we have done.

- The gender action plan developed by the Convention is going to be comprehensive and it aims to mainstream gender in all activities of the Convention.

Minamata Convention Intersessonal Work:

Addressing human rights only during negotiations will not be conducive, we need to act throughout intesessional periods. The Minamata Convention is actively engaged in fostering the human rights approach ahead of negotiations. Pre COP-5 activities include:

- Compilation of views of indigenous peoples and local communities, and this is reflected in the document that will be part of the ASGM discussion.

- Compilation of data on monitoring of mercury and mercury compounds in and around ASGM communities.

- Provide meaningful engagement with stakeholders, through technical working groups as well as regional meetings, ensuring that there is a clear process in terms of how to participate.

- Brown bag sessions with the Executive Secretary. Various sessions have been organized since this process was started in COP-4 and this has allowed stakeholders to have a direct line to the ES to discuss issues that they are working with and for us.

In the context of the GRULAC regional meeting ahead of COP-5 on 5 October, the Secretary is hosting with the government of Brazil an indigenous people’s dialogue to highlight the priorities and needs of the indigenous communities.

Therese KARLSSON | Science and Technical Advisor, IPEN

- There are over 350,000 chemicals of which only a tiny fraction is regulated. These chemicals are used in a shockingly untransparent manner and are underpinning the current triple planetary crisis.

- The vast majority of plastics and chemicals are made from fossil fuels, and these are exacerbating the climate crisis during production, use and end of life. The growing use of toxic pesticides is a big contributor to dramatic biodiversity loss.

- The pollutants and pollution is also growing at an alarming rate, creating linkages with infertility and growing cancer rates. Toxic chemicals are poisoning communities and jeopardizing human rights all over the world.

- IPEN has been documenting from all over the world that the right to a healthy environment, the right to science and the rights of future generations are being compromised in favor of industry interests. Throughout the years we have seen how plastic wastes are poisoning food in communities all over the world, how waste trade is causing widespread and reckless destruction and jeopardizing countries; abilities to handle their own wastes.

- Techniques that industry actors often claim as the solution such as plastics recycling expose workers and consumers to increasing level of toxic chemicals. Various analyses show how recycled plastics contain toxic chemicals and that workers or consumers receive no information on what they are being exposed to.

- The current negotiations including the plastics treaty’s, the future science-policy panel on chemicals and waste and the work under Basel, Rotterdam Stockholm Conventions, Minamata Convention and others all present amazing opportunities to safeguard the human rights to clean, healthy and sustainable environment, the human right to information as well as the right for future generations.

- To do that, health and the environment need to be at the center of all these negotiations. This will require processes to be transparent and contain robust conflict of interest policies. These should be focused on protecting human health and the environment.

- Industry interests cannot be allowed to guide these processes. It is also important to note the importance of transparent access to information.

- The Stockholm Convention says in Art. 9 that information on health and safety of humans and the environment shall not be regarded as confidential and this is important; this also links to the right of information, it will also require that these negotiations are focused on upstream measures. Waste issues are of course important but they are only symptoms of the underlying problems.

- If we do not address the issues of toxic chemicals at the extraction and production phases the waste will only continue to grow, we need to decrease production overall and we need to regulate the production and use of chemicals focus on a rapid phase out of toxic chemicals that are causing harm or have the potential to cause harm on human health and the environment, this work will be important.

- The precautionary principle is guiding, this means that lack of full scientific certainty shall not be in hindrance towards taking regulatory action to protect the human right to clean and healthy environment; protecting this right will also require that chemicals are regulated as groups whenever possible.

- We see repeatedly how one toxic chemical is substituted with another toxic chemical often from the same group of chemicals. Today there are over 350,000 manufactured chemicals and we simply do not have the time or the resources to use a chemical-by-chemical approach in order to protect the human right to clean environment and the rights for future generations. We must work more efficiently with regulating chemicals and eliminating toxic chemicals as groups.

Ana Paula DE SOUZA | Human Rights Officer, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

- We have enough evidence to establish that toxic chemicals are responsible for ongoing massive human rights harms that negatively impact multiple aspects of human life and dignity. The UN, including the Human Rights Office, the Special Rapporteur and other agencies, scientists, civil society organizations, indigenous peoples, frontline communities unions, and states amongst others have been highlighting for quite a while the multitude of impacts of chemicals and waste in the environment in our health and in our life.

- Despite all this, there is a huge disconnect in environmental negotiation and the approach has been silent, including at the national level. It has been said that human rights are too political and too controversial: if we mention human rights is going to stall negotiations. There is a constant work of demystifying what human rights are about.

- If we do not deal with this crisis with a holistically integrated approach we will continue being stuck with a lack of ambition and of urgency that must guide us and discuss solutions and alternatives that can be inadequate or even worse harmful and misleading.

- Human rights promote and provide the road map for the ambition that is needed in these negotiations. Crucial issues concerning environmental justice equity and common but differentiated responsibility, intergenerational equity, discrimination against people in a vulnerable situation and the responsibility of business are often overlooked.

- Greater awareness of the obligation of progressive realization found in the international committee and economic social cultural rights, into the chemicals and waste discussions would level up the discussions, while acknowledging that states do not have the same point of departure when it comes to resources and capacity. at the same time providing new MEAs with more teeth when it comes to implementation.

- We must not forget that human rights standards and obligations already guaranteeing all people the rights to participation access to information and access to justice in environmental matters. At chemicals and waste discussions we hear a lot of buzzwords such as participation, transparency and more rarely accountability. Those principles have equivalent rights that carry the obligations of two states and have been included in environmental sound agreements such as Aarhus and Escazu: we need to promote the shift in the negotiations if we have to face the toxic crisis head on there.

- There is much talk about the precautionary principle which is key and should always be applied. There is not so much talk about prevention. The duty to prevent exposure from toxic derives from the rights to life and health. All states are already bound by those obligations and ensuring that they are applied to environmental matters is exclusively a matter of coherence, a renewed political commitment to respect protect and fulfill human rights.

- During negotiations Civil Society organizations, the UN, and an increasingly large number of member states are increasingly clear on the need to incorporate the human rights frameworks into the chemicals and waste discussions.

- Those calls disappear from summary reports and more concerning from the zero draft of the plastic treaty. We hope this will be addressed in the coming INC. The plastic treaty should be adopted by 2025, 10 years after the Paris Agreement was adopted. In view of all we have learned from science and experience as humankind the three of the hottest months that have ever existed on Earth, we need to aim for greater ambition the Paris Agreement has. We hope that the plastic treaty sets a new bar including human rights as part of obligations, as it is impossible to talk about health without talking about the human right to health.

- Human rights mechanism also have their role to play in breaking silos, while there is a lot more that needs to be done we have found that in addition to the Mandate of the Special Rapporteur on toxics, the Special Rapporteur on Environment, the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, the Special Rapporteur on water and sanitation, the Special Rapporteur on violence against women its cause and consequence and the Committee on the elimination of discrimination against women and the committee on economic, social and cultural rights have issued recommendations.

Closing Remarks

Marcos ORELLANA | UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights

- Sometimes chemicals and wastes are a subject eclipsed in public opinion, also considering their complexity as we deal with various substances, increasing fragmentation and making progress harder.

- The Basel Convention is instructive to look at. The Basel Ban Amendment began to close a huge gap in that instrument. It was a very important step forward and it shows that at times bans do have a place. It is not just reduction or minimizing, there may be situations where bans are needed. Recent debates at the Rotterdam Convention highlighted this again.

- If we look back at the preparatory works of that instrument, China proposed a ban on the export of hazardous pesticides that had been banned in their countries of origin. The Convention articulates what is a shared responsibility based on risk management and decisions by importing countries. Importing countries do not always have the capacity for those assessments and so this construct begins to break down and instead begins to come from industry.

- There are unfinished businesses with regards to highly hazardous pesticides in international trade and perhaps ICCM5 can begin to put it not only on developing countries that have challenges when it comes to implementing assessments or interactive dialogue.

- The Human Rights Council itself has ratified the Stockholm Convention, the original Dirty Dozen but has not ratified any of the amendments of the new lists of persistent organic pollutants, there are internal regulatory issues and governance system part of this but it goes to show that the dynamisms instruments are not always reflected.

Highlights

Video

Live from Youtube

Live in the Room