Event Conference

Perspectives on Solar Radiation Modification Governance

12 Oct 2023

10:00–12:00

Venue: International Environment House 2 & Online | Webex

Organization: Geneva Environment Network, Switzerland

This event, organized by Switzerland within the framework of the Geneva Environment Network, took stock of recent publications referring to Solar Radiation Modification bringing together stakeholders from different fields to provide their perspectives on solar radiation modification governance.

About this Session

Increased and urgent action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, phase out fossil fuel, and invest in adapting to the impacts of climate change remains an immutable goal to tackle the climate crisis.

However, current efforts remain insufficient. Scientists and policy makers acknowledge that even drastic emission reduction over the next years will not be sufficient to limit temperature rise and meet the 1.5–2°C goal of the Paris Agreement. No pathway envisioned by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) could limit global warming under 1.5°C through emissions reduction alone (IPCC, 2018 & 2021).

As the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Executive Director Inger Andersen has raised in the UNEP Independent Expert Review (2023), increasing number of voices are calling for preparing “emergency” options to keep global temperature rise in check. Technologies that can artificially cool the planet, such as Solar Radiation Modification (SRM), could be seen as tools to counter the negative effects of the climate crisis, as they have potential to offset warming and ameliorate some climate hazards (IPCC, 2022)

On the other hand, though SRM could offset some of the effects of anthropogenic warming on global and regional climate, large uncertainties and knowledge gaps are associated with the potential of SRM approaches to reduce climate change risks (IPCC, 2022).

If CO2 concentrations continue to increase, there are concerns over unseen impacts caused by large-scale SRM approaches that could lead to an increased chance of a devastating impact on ecosystems of a sudden and sustained cessation of a large SRM deployment (the ‘termination shock’) (UNEP Independent Expert Review, 2023).

Moreover, despite increased calls for the study of SRM’s effects, there are concerns over potential impacts on the effective enjoyment of human rights these technologies can have on communities, especially of those in already vulnerable situations. As UN Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights highlighted, though climate action is indispensable and urgent, “it is neither legitimate nor sustainable if it exacerbates toxic pollution and the concomitant human rights infringements.”

Within this ongoing discussion, this event taking place ahead of the sixth session of the UN Environment Assembly (UNEA-6) took stock of recent publications referring to SRM. These include the UNEP Independent Expert Review on solar radiation modification research and deployment, the report of the Human Rights Council Advisory Committee on the impact of new technologies for climate protection on the enjoyment of human rights (A/HRC/54/47), the UN Convention on Biological Diversity on certain restrictions on solar insolation activities that may affect biodiversity (CBD/DEC/X/33/8w), and mentions of SRM in reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The event, organized by Switzerland within the framework of the Geneva Environment Network, brought together stakeholders from different fields to provide their perspectives on solar radiation modification governance.

Speakers

By order of intervention.

H.E. Amb. Felix WERTLI

Switzerland Ambassador for the Environment | Chair

Andrea HINWOOD

Chief Scientist, UN Environment Programme

Patrycja SASNAL

Member of the Advisory Committee to the Human Rights Council | Head of Research, Polish Institute of International Affairs

Anthony PATT

Lead, Climate Policy Lab, ETH Zürich | Coordinating Lead Author, WGIII Sixth Assessment Report, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

Pascal LAMY

Chair, Climate Overshoot Commission | Vice President of the Paris Peace Forum, former Director-General of the World Trade Organization

Cheikh Ndiaye SYLLA

Director of Ministerial Cabinet for Environment and Sustainable Development, Senegal

Marie-Valentine FLORIN

Secretary General, International Risk Governance Council (IRGC) Foundation

Lili FUHR

Director, Fossil Economy Program, Center for International Environmental Law

Highlights

Summary

Opening

H.E. Amb. Felix WERTLI | Switzerland Ambassador for the Environment | Chair

The recent assessment report of IPCC shows that we’re not on path to limit global warming to 1.5 degree. In the current scenarios, there will be likely an overshoot. In the context of this potential overshoot, there’s a growing discussion about potentially emergency options. One of those options under consideration is solar radiation modification (SRM), a family of approaches that could potentially offset some climate change impacts.

However, SRM also carries uncertainties and major risks of adverse impacts on food security, environment, global security, and international cooperation. An additional risk of SRM is that enhanced discussion could lead to decreasing efforts for mitigation and adaptation. In a moment where we have to be ambitious and to increase our current efforts, it is the view of Switzerland that it is very important that policymakers are informed with what is happening in the field of SRM, and have a possibility to consider if the current governance and information frameworks are fit for purpose or if additional work on national, regional or global level is required.

We recently have reports published regarding SRM. They look at the risks and challenges and some of them are related to the governance questions. We thought that it would be very timely to provide to some actors the opportunity to present their reports and findings and discuss them jointly from different perspectives.

What has been said about Solar Radiation Modification?

UNEP Independent Expert Review — Andrea HINWOOD | Chief Scientist, UNEP

Context | We already know that we’re warming too quickly, that we’re not on track to meet the Paris targets, and that we require very fast action to reduce greenhouse gases to avoid this warming increase, which has the flow-on effect to the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events such as the melting of the polar and glacial ice, sea level rise, among many other changes. This is why this issue of solar radiation modification has come up. Often, it’s called geoengineering but also climate-altering technologies and measures (CATM).

We’re tending to use solar radiation modification in one sense but there are a whole group of technologies which could have an influence on the climate, amongst other facets, called climate altering technologies and measures. They are increasingly being scrutinized discussed and debated because people are worried that we’re not doing enough to meet the Paris targets. Debate on these possible technologies is polarized.

What is solar radiation modification? | They’re effectively a group of technologies that aim to cool the planet. One of the key facets we must consider when we talk about these technologies is that SRM does not reduce, remove, or manage greenhouse gas emissions. Even if SRM worked to cool the planet, it still is not doing anything to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions, which would then have subsequent impacts on the climate.

In the One Atmosphere report by UNEP, stratospheric aerosol injection is being studied and discussed primarily because it’s where the most information exists. We know more about this particular technology compared with other technologies and there are others being explored. Most of the research that has been done in terms of stratospheric aerosol injection is based on volcanic eruptions. These have shown that when those aerosols go up into the stratosphere, they can cool the planet within a fairly short period of time. All of the work that has been done on this is modeling-based. It’s largely theoretical, and at the moment, the modeling studies suggest that deployment of aerosols could cool the planet.

However, there are a whole range of issues around how this would be deployed, how much is needed, what are the subsequent effects.

On what do we know and what we don’t know.

- There is very limited literature on uncertainties and risks. This report was generated by nine experts who came together across a range of areas: from ecological and social impacts to the atmospheric sciences. What was very clear was that while there was lots of modeling work done on, for example, stratospheric aerosol injection specifically, there was very limited information on the uncertainties, risks and impacts. There is certainly no international consensus on the risks of SRM.

- Another key facet was that if you deployed a stratospheric aerosol injection, the cooling effects would diminish if you halted it very quickly. To illustrate: you’re still emitting greenhouse gases, then you apply a technology to cool the planet a bit. Then, even when you remove that technology, you have all the greenhouse gases that have been building up, leading up to a potential for termination shock, i.e., a big increase in temperatures and associated impacts. There are some suggestions it could delay the closing the ozone hole, could have impacts on the warming of polar regions, and the cooling of the tropics.

- It’s also seen as the slippery slope to deployment: when research and modeling become field experimentation which then leads to deployment. This is one of the key issues around considerations of governance.

- These technologies are also seen as potentially influencing geopolitics, as most of the work takes place in the global North. We already know that developing countries in the global South are already deeply impacted by climate change, but they’re also not being engaged at all in this area of development. This is something that the panelists we brought together felt very important.

Some key concerns.

- Limited focus on potential environmental impacts. This is why UNEP is interested in this: we have a mandate to keep the environment under review, and that includes technologies that could have a significant impact on the environment.

- Decisions about SRM and deployment would not be made in a globally inclusive, equitable and transparent manner. There are concerns about this because most of the research occurs in the global North, with little discussion with our participants in the global South. If someone deployed these technologies unilaterally, it would impact all of us.

- SRM discussions could shift action from mitigating climate change to focusing on SRM. SRM does not solve the problem of greenhouse gas emissions and accelerated climate change. We need to keep our eyes on the prize: to reduce greenhouse gases and limit our warming.

- There is no governance over research indoor experimentation small-scale or large-scale deployment.

There are a range of recommendations that are that are outlined in the report, but I want to make it very clear that the UN is not promoting research. It is recognizing that research is afoot, and we would be naive to think that it’s going to cease all of a sudden. There’s increasing attention because we are not paying attention to climate change mitigation and adaptation. But fundamentally SRM does not solve the problem that we’re experiencing, so we need to be very mindful and keep our focus on that.

- SRM technologies are fraught with uncertainties and potential risks. We have complex issues of ethics and governance: where do you place the lines of looking at ethics and governance with modeling studies and what is field studies? For someone who’s looking at measuring aerosols in the atmosphere, is that deployment or is that a way of detecting whether someone unilaterally deploys?

- A precautionary approach is always required. Our experience over history tells us that this issue will be no different to many of the others. The panel and UNEP are firmly of the view that we need to bring a level of scientific discipline and evidence to the table to enable us to have a really good discussion about SRM. That means that we understand who is doing what, where they are doing it, what type of research, what the outputs are, whether they are factoring in considerations of environmental, social, and economic impacts, whether they are discussing this with researchers in the global South, among others.

- One of the key issues for UNEP is that we do believe there should be a comprehensive ongoing scientific review process to enable us to pick up research as it comes out, so that we understand what the implications of research that becomes deployment, and the potential for deployment down the track.

I also think that it is important in this space to maintain neutrality. This is why science in many ways is the safe space. It is a very polarized debate and it’s potentially distracting from action on climate change, so if we can have a very good robust discussion that is neutral and that enables us to look at who’s doing what, whether these technologies are financially feasible or not, is something that we could do in a global discussion. We certainly should start discussing:

- What form of governance framework?

- What would it look at? Would it consider small scale experimentation or is it only focused on deployment?

- Could we set up a register of those that are researching in this area so that we consider some of the obligations that researchers have in terms of this field where there is great uncertainty and risk? and

- Where the impacts could be significant both for regions and globally?

Advisory Committee of the Human Rights Council — Patrycja SASNAL | Member of the Advisory Committee to the Human Rights Council | Head of Research, Polish Institute of International Affairs

The Advisory Committee is supposed to be a think tank of the Human Rights Council, and we were mandated to prepare this report two years ago. In the report, we assess several geoengineering technologies, impacts, and risks in the physical, political, ethical, and social spheres. We also assess their impact on specific human rights in specific groups, such as Indigenous Peoples, peasants, fisherfolk and other rural people, and frontline communities. We indicate that the applicable normative framework argues for a principled approach and a protective framework, including governance inclusiveness in decision-making, ensuring accountability, and oversight access to information, participation, and access to justice in environmental matters. We believe that a human rights-based approach helps to ensure that state policies are not regressive in human rights terms and can effectively improve the lives of all people, including through the realization of the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment.

In the report (A/HRC/54/47), we assess the two broad kinds of geoengineering that is carbon dioxide removal and solar geoengineering. What I will now speak about are concerns regarding solar geoengineering, and is taken from the report. I will focus on the main premises and conclusions, but I invite you to look into the report.

Some forms of solar radiation management, notably stratospheric aerosol injection, may result in regionally and globally unpredictable changes in hydrological patterns, in harm to the ozone layer, in dimming [that can lead to] reduced photosynthesis, crop growth changes, and further cascading risks in the social and political systems and relations, such as food shortage, migration, and political conflict. Despite the presumed decrease in average global temp temperature, all these risks would be amplified by the fact that once applied at scale, stratospheric aerosol injection could be irreversible and cause geographically uneven, and potentially international conflict, provoking consequences, and would have to be continued to avoid the rapid and extensive warming after immediate cessation, or termination shock.

The social consequences would likely be uneven geographically. For example, through the hydrological cycle disruption which would potentially be harsher for poorer States, frontline communities, and the global South in general, depending on where certain technologies are used. That might in turn strengthen entrenched inequalities and deepen climate injustice.

In the social realm of risks, surveys show that people worldwide are not familiar with geoengineering and solar geoengineering in general. That may result in increased distrust should a technology be used on a larger scale, fueling conspiracy theories in relation to geoengineering given the popularity of disinformation campaigns and their usage as tools of internal and international conflict. Climate technologies may become their subject. In this case, it may be increasingly difficult to conduct an informed public debate about these methods. That, in turn, would add to the growing distrust of technology and science.

A general moratorium on some forms of climate-related geoengineering was introduced by the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2010, given the lack of transdisciplinary research. Hostile use of weather modification technologies is already prohibited under international law. Still, even peaceful use of such technologies could pose immense risks and result in negative human rights impacts. If climate becomes a tool a state can use against another state, such an action could radically change climate politics, making it a security issue. The use of solar radiation modification could bring about an unknown political and social order.

One of the risks — an ethical risk — that we underscore in the report is the moral hazard risk. These technologies, solar geoengineering in particular, can act as a deterrent to cutting emissions. It makes disastrous future scenarios more probable. At the moment, a number of civil society organizations, Indigenous Peoples and researchers whom we have consulted in writing the report underscore that counting on technological solutions (1) slows down reforms to cut emissions, including investing in renewables and the circular economy, and (2) diverts public attention away from the primary goal being cutting emissions, giving the false promise of a hypothetical future solution to a problem that requires immediate action now.

I want to underline that this moral hazard risk is sometimes diminished. It is a complex phenomenon: we cannot assess with precision what impact it can have on people’s and government’s decisions. However, since there is a possibility that it will deter both bottom-up and top-down changes in behavior and decision-making, it has to be taken seriously. Time and all kinds of resources, financial and human, spent on one thing means that they will not be spent on another.

The report points to the fact that solar geoengineering can potentially interfere with many fundamental rights: the right to life, to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment, the right to information and public participation, the right to an adequate standard of living, and the right to food and water, as well as access to justice and remedies. It transgresses boundaries and puts obligations on future generations. I want to particularly highlight the right to free, prior and informed consent of the Indigenous Peoples, which has been at least once, if not twice, violated when it comes to an attempt to have a field test in relation to solar geoengineering (Annex of A/HRC/54/47, par.15).

Conclusions. The two main conclusions that we draw in the report are:

- The precautionary principle has been and should be applied to geoengineering, including solar geoengineering. States have a general obligation to adopt legislative, administrative, judicial, and other measures to prevent harm to the environment at an early stage and to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction or control do not cause damage to the environment of other states or of areas beyond the limits of national jurisdiction.

- Solar geoengineering can interfere with the enjoyment of human rights and cause physical, political, and social risks to frontline communities including Indigenous Peoples, and harm the environment. There is scientific uncertainty about the side effects and there exist less risky alternatives. It is urgent to underscore that at present the development of such technologies and policies to support them would not be in accordance with the protective standards of the human rights regime without an adequate protection framework. It is hard to envisage how technologies aimed at manipulating climate could be developed and used for the good of humankind, at this stage of their development given the lack of sufficient knowledge of the risks and adverse impacts. It might be better to presume that geoengineering is generally harmful to humans, harmful to human rights, and its deployment would be contrary to the existing obligations of States because of the moral hazard risk. These technologies limit emission cuts and systemic changes which are urgently needed.

We also recommend that States adopt and implement restrictive regulations on solar radiation modification experiments where necessary, including a ban on outdoor experiments while only allowing conditional and controlled research. The lack of a mechanism to prevent the development of harmful solar radiation modification techniques should be addressed in a manner that includes the global South and climate-vulnerable States and communities.

We believe that we do work in the risk framework. All actions have risks and side effects, but in the risk framework, the risk of doing solar geoengineering is greater than that of not doing it. When it comes to governance, with the current state of international affairs ridden by conflicts, open, direct, or indirect, it is almost impossible to come to a consensus when it comes to solar geoengineering, be it deployment or research. States can, in the future if they resort to using solar geoengineering, create a new political international environment and a large division among interventionist States and non-interventionist States causing a new line of global division.

Time is a factor. We have around 20 years to 30 years, when we know what needs to be done: cutting emissions. Whatever is there that takes away the attention from the primary goal of cutting emissions is not conducive to human rights globally.

IPCC Assessment Reports — Anthony PATT | Lead, Climate Policy Lab, ETH Zürich | Coordinating Lead Author, WGIII Sixth Assessment Report, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

The results that we came to were very similar to those in the UNEP report. They are maybe a little less strong than what Patricia just talked about coming from the human rights perspective. It’s worth bearing in mind that the IPCC is meant to be policy-relevant, but not policy prescriptive: we stay away from making definitive statements about what policy should be.

One also needs to recognize that the space that we had to consider within the IPCC report and the amount of time that we had to spend on it was far more limited than, for example, in the UNEP report.

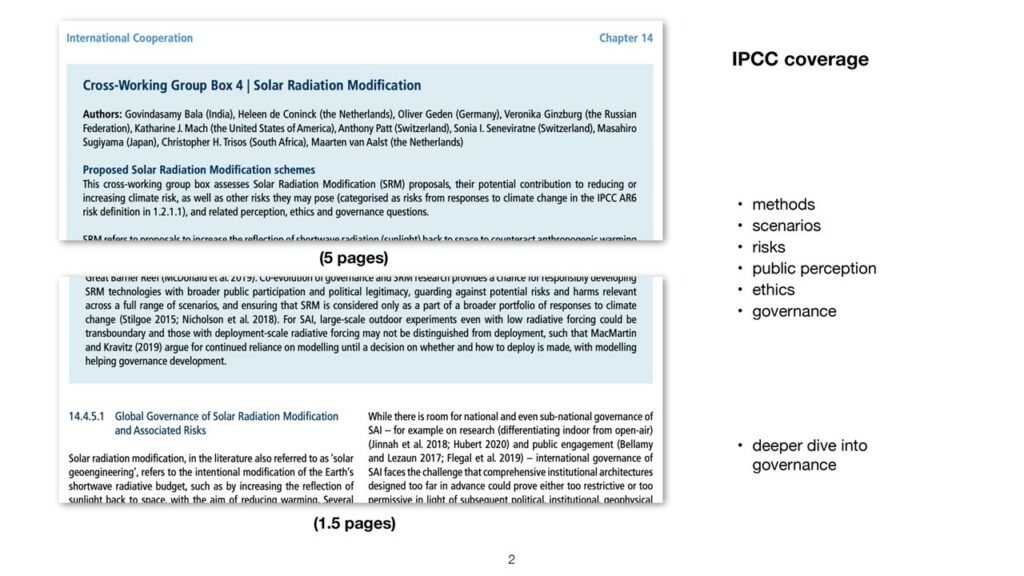

Structure | There are three working groups (WG) in the IPCC report: WGI focuses on climate science, WGII on impacts and adaptation, and WGIII on climate mitigation. In the original scoping, it was decided that [SRM] would be dealt with in WGIII, within the chapter on International Cooperation, of which I was the coordinating lead author. There was also a decision to have a cross-working group box, to be written by scientists from all three working groups, where the same version of the box would appear in each of the three reports (Cross-Working Group Box SRM, p.76). The box was composed of five pages and dealt with a number of issues: methods, scenarios, risks, public perception, issues, ethics, and governance. Within the WGIII report, we had a deeper dive into the governance.

Scenarios | We looked at the fact that there are multiple methods for solar climate intervention. We noticed that most of the research has focused on stratospheric aerosol injection — which has global coverage, is the most heavily researched and discussed, has the most developed scenarios for implementation, and, despite a very incomplete analysis of risk, has progressed the furthest.

There are multiple scenarios on how SRM could be deployed. The most drastic deployment would be the permanent use of SRM where it would replace conventional mitigation strategies. If you didn’t have SRM, you would have a temperature path that was continually rising, and if we wanted to constrain global average temperature rise to 1.5°C to 2°C, we would have to have ever larger amounts of SRM. What we notice in the literature is that there is pretty much universal agreement and consensus that this is not an acceptable use of SRM. The risks are simply too great if it’s increasing in magnitude.

Permanent SRM use scenarios

We also note some opposition to the permanent use of SRM, where it would augment conventional mitigation, in a case where conventional mitigation led to a temperature overshoot (seen in the lower graph where conventional mitigation might lead to 2°C warming). The intention was to use SRM to bring us down on a permanent basis to 1.5°C warming.

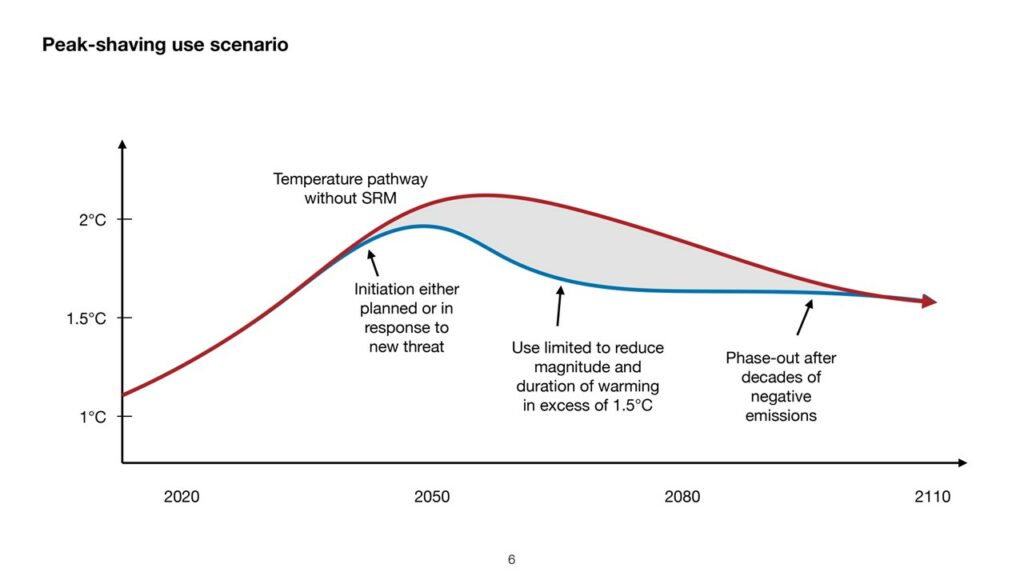

Peak-shaving use scenario

There is also some recent literature on using SRM in a peak-shaving scenario. If we had a period of temperature overshoot (red line), where for several decades we had warming in excess of 1.5°C and we’re deploying very large-scale carbon dioxide removal to reduce atmospheric concentrations of CO2, you would nevertheless have many decades of temperature 1.5°C. SRM could be used to limit some of that. To keep the temperature rise to 1.5°C, SRM would be initiated either in a planned manner or in response to some new threat. Its use would be limited to reducing the magnitude and duration of warming excess of 1.5°C, and it would be phased out after decades of negative emissions.

While the IPCC certainly has no recommendation to do this, we note that there are scenarios for this kind of deployment that do appear to reduce climate risks.

risks include the risk of a sudden warming from a sudden discontinuation of the SRM. If it were deployed and then were to cease all at once, the temperature would rise rather rapidly.

There are also indirect risks, and these are ones arising from the societal responses to SRM use.

- As we’ve heard, there is also the moral hazard risk, including the possibility that conventional mitigation stops because we are using SRM or the incentives to reduce emissions and get to net-zero ends.

- Yet to be assessed in literature is the moral hazard of negative emissions falling away because, in virtually all the scenarios that get us 1.5°C warming, we do have overshoot and have multiple decades of carbon dioxide removal. One could imagine that if because of SRM deployment, we’re holding temperature rise to 1.5°C, the incentive to engage in those negative emissions becomes lessened, and we just simply don’t do it. We then find ourselves in a situation where we need to continue using SRM if we want to limit temperature rise.

- Finally, the indirect risk of interstate conflict, associated with one or some states deploying SRM — perceived as a violation of international law. This could lead to a conflict situation which raises the perceived need for strong governance, even before we even go down any of these pathways.

On polarization, there’s a very wide range of attitudes, beliefs, and positions – from making the decision now to never use SRM, from governance that would be a global non-use agreement to a decision now to plan to use it which would then require agreements, covering research, testing, coordination and governance. In between, which is where most of the literature is located, is the idea of preparing to use it, if future events warranted, and then we would need agreements, covering, research and testing the conditions for its use, and the coordination and governance of its use.

The current political status is that each of the three standpoints has support within NGO and scientific communities. No state has formally signaled support for any of the standpoints, although some have implicitly signaled support for the middle standpoint by proposing further research.

Full disclosure: I have signed a statement led by scientists that supports the middle standpoint.

In the report, there are some near-term objectives of global governance (derived from Nicholson et al. 2018, Climate Policy):

- Guard against potential risks and harm from its deployment,

- Enable appropriate research and development in the event that we would decide to use it,

- Foster transparency to legitimize future decisions, and

- Ensure that SRM is only one part of a broader policy portfolio.

These authors also propose a number of immediate interventions that one could make:

- Develop a transparency mechanism: scientific and technical information, project development and legal compliance, funding sources and use, so it is clear who is doing what;

- Establish a global forum: a venue for dialogue between states, non-states, and multilateral organizations leading to potential agreements whether for non-use, potential use, or use; and

- Incorporate SRM into the Global Stock Take under the Paris Agreement to provide guidance into the fit between SRM and other Paris objectives and mechanisms.

Final concluding thoughts, as a scientist and on what has been observed having worked within the IPCC:

- SRM is highly politicized, and its various dimensions overlap with sharp ideologically driven perspectives and principles.

- For scientists there are strong perceived risks associated with saying anything about SRM governance due to the likelihood of being seen as engaged in advocacy.

- It might be good to normalize discussions of SRM governance sooner rather than later.

Climate Overshoot Report — Pascal LAMY | Chair, Climate Overshoot Commission | Vice President of the Paris Peace Forum; former Director-General of the World Trade Organization

The Climate Overshoot Commission was established by the Paris Peace Forum and is composed of a variety of independent people having to report to no specific institution scientific or political. We are independent and multi-continental and have a variety of scientific or climate expertise and experience. The Commission was backed by a rather strong scientific secretariat.

The Climate Overshoot Commission has recently issued recommendations, which are within the same mind frame as the previous speakers. This is true as well for the evaluation of the risks of solar radiation modification technologies. On the other hand, the possible benefits and risks are very clear and the benefits for the moment are less clear. This is the thrust of our recommendations are a sort of middle way: we believe we should link closely the governance of research on SRM and the governance of possible recourse to some kinds of experimentations.

The main thrust of our recommendations is about a moratorium on the deployment of solar radiation modification. The criteria with which we use a moratorium on experiments is whether it would entail a risk of transboundary harm, a category already recognized in international law. Our recommendation is not that we should negotiate the terms of the global moratorium, but that sovereign nation states should individually unilaterally enter this moratorium. The first ones to do that would put pressure on the possible followers, and possibly institutionalize international governance dialogue on this research.

We made a series of recommendations that is about ensuring transparency, sharing North-South equilibrium of both researchers and discussions, and transparency of funding. This research should be evaluated globally, independently, with public involvement including from stakeholders. This is the thrust of what we propose.

The Climate Overshoot Commission is not a commission on solar radiation modification, but has the purpose of reviewing options, in the likelihood that we overshoot 1.5°C (which is not inevitable but the risks of overshooting are increasing every day, given the huge challenge of global warming). This report, published in New York and handed over to the UN Secretary-General, is a whole review of the CARE agenda: cut emissions, adapt, remove carbon, and explore solar radiation modification, where C comes before A, then R, then E.

SRM is not something that addresses the root cause of global warming — carbon dioxide emissions. It is as such sort of a last result. I want to make this extremely clear because part of this ideological debate which has already been mentioned on solar radiation modification stems from one criticism which is that it would entail a risk of distracting attention from what really needs to be done. We have clearly detailed recommendations on how to increase the speed of cutting emission, how to enlarge and finance and measure adaptation, how carbon removal should be handled, including considering take-back obligations.

The recommendations made on SRM are only one part of a much larger agenda, which we believe is absolutely necessary now. Our hope is that this will trigger the necessary attention and will help ramping up action against global warming.

Conclusion. On a note of a recommendation, why not consider that Switzerland would be the first of the countries to adopt a unilateral ban moratorium on specific experiments on solar radiation modification. We stand ready to help drafting what such a declaration should look like.

Q&A

H.E. Amb. WERTLI | Building on the point raised, next February will be the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA), which will be held in Nairobi. UNEA is the world highest decision-making body for matters related to the environment. As mentioned in the presentations, we need a stronger dialogue on SRM.

Q: Would you have any expectations for the next UNEA — should UNEA take up this topic or take any decision on this topic related to SRM and its governance?

Andrea HINWOOD | I can’t comment on what UNEA-6 and what member states would consider in terms of a resolution or action. What I can say is that I think that there would be benefit in both pursuing a scientific review of this topic that considers the broad array of issues that have been outlined in this fora Whatever mechanism is developed, there is a need for that. Anthony put it eloquently in terms of the transparency required in terms of ongoing research and that may extend. I think that is useful thing that should be put in place. One of the key issues for me is the engagement with the Global South. We are leaving out large parts of the globe, and not engaging in a discussion on technologies that should there be unilateral deployment that could impact all of us.

I would just reiterate that those are key issues for UNEP. They are issues for member states but in terms of UNEA-6, I can’t comment on that.

Patrycja SASNAL | To stay in line with the recommendations of our report, I would have to say that solar geoengineering discussions at the UN level should be ideally put on hold. If they are not, it is of utmost importance that any talk is transdisciplinary and truly global.

Transdisciplinary means that scientists and experts from all fields of sciences are included because this has not been the case until now. More involvement of scientists in humanities, social sciences, political sciences, as well as stakeholders should be included in all of the discussions. [Truly global means] that the Global South should be included. This is not an easy task because there are attempts to include people who come from the Global South, but it is to my knowledge not a genuine effort to include their views in what comes out in literature.

The ideal situation to me would be that the scientific circles themselves decide in their own circle on the way forward on how to go about research. This is the question that we should be talking about, certainly not deployment. When it comes to research governance, and there have been attempts already, I think the White House of the United States is working on governance of research on solar geoengineering. I think it would be up to the scientists themselves to come to a sort of a global understanding on how to go about further research in this matter.

Anthony PATT | The IPCC can’t offer any advice on what anybody should do. We really try to stay away from being policy prescriptive in any way, and indeed recommending that UNEA do or do not do something would be a bit intruding onto policy prescription. What I can say is that the literature we assess on the governance of SRM has a lot of different viewpoints in it. Some would echo the thoughts that Patricia had, that ideally UNEP should not take up its discussion because that could create moral hazard risks which would be larger than what it is able to achieve.

On the other hand, there are viewpoints in the literature – not exclusively scientific literature but includes philosophical thought – that raise concerns that SRM could be deployed by a single state, a non-state actor or a group of states or non-state actors. In such a case, it would be good to have international discussions and guidance on what to do in such situations before it happens. That would then be an argument in favor of bringing it up at an international body such as UNEA

Pascal LAMY | I don’t have to take any institutional precautions. As somebody who’s independent, and speaking on behalf of colleagues in the Commission, I think the main point to make is that there needs to be a solid, science-based international discussion about solar radiation modification. It is too important not to do so, and to leave no stone unturned given the urgency of actions against global warming. On the other hand, SRM is a risky option. We need informed urgent discussions about the pros and cons, on what to do. There are a variety of recommendations on the table including one that was tabled a few weeks ago.

Second, where should this international discussion be? It’s fine to say that we need a discussion, but if you don’t say how to organize it, it probably won’t go that far. UNEA for us, at the moment, is what comes to mind. It does not mean that it can be the only one, but given what we know of the mandate of UNEP, given what has already taken place when discussions on UNEA started on this issue, we believe that this would be a very fitful purpose. Although associating other international organizations including within the UN system, such as WMO and UNESCO. The Ethical Science Committee of UNESCO is preparing a recommendation which may be published beginning of next year on the ethics of geoengineering science. I think the UNEA could be the place with input from other bits of the international system whether on science or governance.

Q: Jean-Pierre REYMOND, Head of 2050Today, for Pascal LAMY | I very much welcome and salute your recommendation to have a moratorium, but the way you have phrased it, don’t you think it’s somehow a weak recommendation?

As you said, it should only be on large-scale experiments, so who is going to define it and what it means is difficult. You also recommend that it should be unilateral, so if a few countries do it, but the vast majority don’t, how is it going to be relevant? Third, you propose to expand research: it means that even if you have a moratorium, you continue to imagine solutions, which at some point will weaken the moratorium.

Pascal LAMY | Expanding research with a framework of rules — a sort of research governance users notice which we propose in our recommendations. As far as experiments are concerned, and we recommend research, we go to the question of what sort of risk should be addressed in deploying, even for experimental reasons, solar radiation modification, we propose what we call for the general public large scale. However, the precise criterium which we propose to use, and which is already recognized in international law is experiments entailing a risk of transboundary harm. The notion of transboundary harm is already recognized: it’s not just the country next door, but it’s also the high seas or space that have no specific jurisdiction in terms of territorial occupation.

A unilateral moratorium is, in our view, the quickest way to get there. There is an option of negotiating a global moratorium, where countries can enter into a code or a treaty which will take an awful lot of time. We believe it is urgent and my experience in international governance shows that if a series of countries start saying these are the conditions under which they unilaterally adopt a moratorium to address the risk of deploying large-scale SRM, then this will have a snowball effect. The ball will then be in the court of those who do not accept the moratorium. We believe that in terms of international diplomatic governance dynamics, starting with a few countries that will then give a signal to others is the right way to go if we want this to happen relatively quickly. We believe it is urgent because there is always the risk.

Francesca MINGRONE, CIEL | It’s very important to have these conversations with a wide range of actors. To echo what has been said by Patrycja Sasnal, the importance of putting human rights lenses in the debate is clear.

We’ve seen across all the presentations the direct impacts and huge risks that a deployment of solar radiation modification technologies would imply. When we talk about potential ecosystem collapses, termination shocks, and so on, we shall not forget the human face. This is really what the human rights framework and a human rights-based approach provides. That’s why the report of the Advisory Committee is so essential because it’s the first one that addresses the question of geoengineering from a human rights perspective and identifies not just what the substantial risks are in terms of human rights protection, but procedural risks as well.

A big part of the report looks at the issues of consultation of meaningful participation. We have already seen that many experiments are being conducted with no consultation or participation of Indigenous Peoples, for instance, on whose lands these experiments are conducted. There is also the question of meaningful participation of Global South actors. More and more mechanisms in the human rights field are also addressing these questions, such as the Committee of the Rights of the Child that also mentioned the risks associated to human rights impacts of geoengineering technologies. We also heard from the Special Rapporteur on the environment and the Special Rapporteur on toxics, among others. Let’s not forget to include these actors in the debate.

Another comment is in reaction of what we’ve discussed between the difference between experimentation and deployment: this is a very fine line. For instance, for stratospheric aerosol injection to have meaningful experiments that would allow us to collect enough data – experiments at large-scale – we need to ask what the difference is between this and actual deployment, while being conscious of the risks in allowing experimentation?

For Professor Pat, in his presentation, he outlined a number of recommendations and scenarios. Just to understand that these information and recommendations are not only taken from the IPCC’s AR6, but also are part of his own understanding as a scientist and as a professor. To what extent were those recommendations for included in the WGIII reports and what came out of his own professional thinking?

H.E. Amb. WERTLI | From what I understood, he made it quite clear that he also made a difference distinction between what he did as part of the IPCC report and was very transparent about his opinions about scientists. He also showed that IPCC is not policy prescriptive, and has limits on what they can recommend. I think in general terms, he has answered the question that you had – that there were different influences in his response.

Yves LADOR, Earthjustice | Pascal Lamy made a very relevant and precise proposal to Switzerland to take a lead at its national level. Can they provide some perspective on this?

H.E. Amb. WERTLI | We had together 12 co-sponsors when we submitted a resolution at UNEA-4 in 2019. The idea was that we need more information on what is happening in the field of SRM. At the time, we called it climate-altering technologies and measures (CATM) – a broader term because governments must be able to consider actions on the national and global level. The first step is to have an enabled discussion: information has to be available.

Secondly, a main concern we have expressed at the discussion was that it was the view of the co-sponsors including Switzerland that we want to prevent unilateral use. That would be a bit of a different approach. That would be kind of a unilateral approach to prevent a certain type of deployment of SRM. I think what is still in the room is that governments, including Switzerland, are able to consider such a proposal. This means that we need a full picture of it, we need to be able to access all the information to and have an overview what is exactly happening. Perhaps, you need a mapping of existing governance frameworks and so on, so that we can also put such kind of action in a broader context. For me, if we wish that governments consider such kinds of proposals, that means we have to ensure that they have access to the full picture.

Stakeholders Perspective

Cheikh Ndiaye SYLLA | Director of Ministerial Cabinet for Environment and Sustainable Development, Senegal

Three steps that allowed us to discuss this very important subject. First, we had a study on geoengineering and African perspectives by an African expert and climate negotiator. The study posed the debate on the problems, vulnerabilities, the elements of positioning and refining Africa on geoengineering and its governance, especially on SRM.

Second, this study allowed us to have a hybrid workshop in Nairobi in January 2022.

- The study showed that participants were deeply concerned that the current level of global ambition of commitments to address climate change are insufficient: they will not limit global temperature increase to 1.5°. This will result in severe impacts on the continent that is already extremely vulnerable and with the least capacity to adapt to climate impacts. The potential impact of SRM technology will add a further burden on a continent that is already experiencing climate change and its impacts

- Africa is also extremely concerned on the focus of financing experimentation, as studies on this technology in developed countries will result in countries shying away from their UNFCCC oblications to implement and finance mainstream proven policies, technologies and measures to achieve the real reduction of GHG emissions.

- Africa is also concerned that a focus on negotiating a governance system for emerging SRM tech will take time, and may divert political will and resources away from obligations.

- Under such uncertainty, Africa should not support their application at this stage, but rather the development of an authoritative scientific synthesis and review of the state of knowledge and technologies, by a mandated body, with a view to inform any possible international policy debate on science and risk-based international management of potential implications, if necessary.

- Africa is further concerned that the SRM technology, (1) will have potentially several transboundary impacts and implications across multiple sectors and areas of legal jurisdiction. Given the global and transboundary nature of this potential impact, it is important for any concern related to the technology to be considered by relevant mandated bodies within the UN system involving all African countries and the African Ministerial Environment Conference at a scientific, technical, administrative, political and legal levels.

- While recognizing the importance of international control to prevent unilateral advancement of SRM technologies and that ensures African concerns are fully addressed pending the review of the current state of knowledge of these technologies as well as the need for further capacity building and consolidation, Africa is not yet ready to support any engagement on possible broader international governance matters related to their technology given (i) the limit level of understanding, and (ii) considering that existing bodies within the UN system have the mandate to address any immediate geoengineering concerns that may arise.

- The African Group of Negotiation on Climate (AGN) will develop further consideration and report to the African Ministerial Conference on Environment for decision-making.

Finally, questions and concerns.

- As we are in the infancy, there are many things that we do not know. What stage are we in the research and/or implementation of SRM?

- Combined with mainstream mitigation and adaptation measures, geoengineering has potential to ameliorate climate change impacts.

- Distinguishing from CDR may require a different treatment.

- We do not have yet the report from the AGN to be submitted to the Minister of Environment.

- In the next AMCEN, we can come back with a recommendation asking about the legality to do the job. We need a place like UNEA to take this matter seriously to have some clear indication for all countries.

READ: Report of the meeting of the nineteenth session of the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment (Advance copy) | 17 August 2023

Marie-Valentine FLORIN | Secretary General, International Risk Governance Council (IRGC) Foundation

The first report published with the International Risk Governance Council was in 2009, entitled “Cooling the Earth Through SRM: The need for research and an approach to its governance.” Following the uh proposed resolution to UNEA in 2019, we produced for the Swiss Federal Government this report — a kind of compendium and resource guide on the range of issues related to climate engineering, both technical and governance. There’s a landscape of what exists, the ongoing discussions at the international level, and concluding with two concluding chapters on possible options for the governance of research and the governance of deployment.

My personal statement at this stage is that given the current climate change, it would be a mistake not to do research on SRM, specifically stratospheric aerosol injections (SAI) research and technical possibilities, the potentials, risks and uncertainties, and research on the governance of research and deployment. Even stronger, I would say it would be a big mistake to deliberately choose to remain ignorant. Ignorance is never something that makes humanity progress. It should be possible to allocate public funding to research, as this is what makes research more transparent and available to all. This is needed to support decision-based solutions, although it may be the case that we will never be able to fully to provide enough scientific evidence to support the decisions. So it should be possible for national research agencies to allocate funding to SRM research without appearing as supporting deployment. This is why this combination of supporting research and perhaps a moratorium on deployment is a right approach.

Since 2020, we’ve produced opinion pieces, that shows in particular the need to support or adopt a portfolio approach to climate change reduction, prevention, emission reductions, carbon dioxide removal, adaptation, which must be developed simultaneously in parallel, and consider solar radiation management. This is a portfolio approach where we probably need everything.

There is the problem of tradeoffs with conflicting objectives. It is not possible to achieve all our objectives, especially when we compare the risks of climate change and the risks of SRM. Thousands of people have very probably died directly from consequences of climate change and millions of people will die in the years to come. This is a serious threat that requires a serious and perhaps different approach to mitigate a problem than a politically neutral way of approaching many technical problems.

One of the last pieces we’ve produced is a framework to help decide about SAI deployment. If and when sufficient knowledge has been acquired, and if it seems that the benefits of deploying SAI would be greater than the risks, or that the risks are acceptable, this framework proposes a set of conditions to deploy SAI. However, it focuses on if and when we know in advance that it should be stopped. Basically, we should never start SAI without knowing that it can be stopped.

- More precisely, the framework suggests that the time to start would depend on whether we are close to crossing one or more dangerous ecological thresholds. This is the first conditions to start deployment.

- If and when research proves that the risks are acceptable, the second condition is that we are quite sure that we are on the path to sufficient CO2 emission reductions globally.

- The third condition for starting SAI deployment would be that there is clarity as to when SAI can be stopped. When we start, we know that we can stop it and phase out to avoid a termination shock. Large-scale carbon dioxide removal to reduce atmospheric concentration should have also been implemented effectively.

To finish, I would like to suggest an analogy with medicine in which there are three very useful principles: (1) the duty to do everything possible to help a patient, (2) the gold standard for risk and safety assessment (i.e., the three-stage clinical tries trials where one first assesses the safety of a technique and treatment, then the efficacy of that treatment, and finally whether the new treatment is better than the existing treatment), (3) and the more a patient is in pain, the more acceptable a difficult treatment with multiple side effects, would be to that person. I’m suggesting this analogy because I think that it’s useful to compare SRM with other technologies to find solutions that maybe we are not familiar with in the climate domain.

Lili FUHR | Director, Fossil Economy Program, Center for International Environmental Law

To begin, the IPCC made it clear that we’re not on track, but they also make clear that proven and readily available solutions exist so that they can be rolled out, referring to phasing out fossil fuels to renewable energies, and reducing energy and resource demand. That is an important new focus in AR6, which includes changing our consumption, production, and our diets. The IPCC made it clear that solar geoengineering is not a solution. To quote, Jim Skea, in a webinar shortly after the release of the Summary for Policymakers, shared, “Many of the authors couldn’t bear the use of the word solar radiation management and insisted on calling it solar radiation modification because of their distaste for it.”

My second starting point is that solar geoengineering research and experiments are not happening in a legal vacuum. Others already referred to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) decision from 2010 that amounts to a de facto global moratorium that remains in place. I want to recall that that decision was based on a full decade of assessments and deliberations.

I also want to highlight that in the marine geoengineering space, which also has solar geoengineering approaches being discussed and researched. The London Protocol and London Convention currently already ban carbon removal technology, ocean fertilization, but the 101 governments forming the governing bodies of the London Protocol and Convention just stated their intention to regulate four additional technologies, two of which are geoengineering. So we do have some governance and more is coming.

When it comes to the reports, I’m surprised to hear so much agreement, and it looks as though they’re saying similar things. I actually think they don’t. For the Advisory Committee report, we welcome and really applaud the report and the Committee for their effort. I want to highlight that this report is part of a whole range of recent reports and authoritative statements coming from human rights experts, and they all agree that solar geoengineering is incompatible with human rights and pursuing it would violate State’s obligations and infringe on the rights of future generations.

When it comes to the report that Andrea Hinwood presented, I want to recall that UNEP did not get a mandate at UNEA-4 to do an assessment, as the Swiss resolution was withdrawn. We also want to share that the two lead authors who selected the other authors for this independent expert report, Professor Ken Caldeira and Professor Govindasamy Bala, are known to be supportive of solar radiation modification, while scientists critical of SRM are conspicuously missing from the report, and governance risks and challenges are inadequately addressed. In this light, proposing governance of potential large-scale operational deployment in my view is not only premature but highly dangerous.

When it comes to the Overshoot Commission, which is a private initiative set up and advised by very prominent solar geoengineering proponents, it is, in our view, not an independent body and has faced severe criticism from within and publicly. We also think that the Commission’s report is quite weak in its conclusions and has nothing new to add when it comes to the core questions of phasing out fossil fuels, adaptation, or climate finance. It’s no surprise that the media picked up the solar geoengineering bit as “the news”.

We welcome that the Commission expresses some degree of caution when it comes to SRM but as one of the participants in this room has highlighted, with its proposal, the Commission risks undermining the existing de facto global moratorium in place at the CBD since 2010. The reference to that is unhelpfully buried in a footnote in the Overshoot Commission’s report because only including deployment and large-scale experiments leave open dangerous loopholes for outdoor experiments that would fall outside of such very poorly defined thresholds.

I also really want to stress the point made that stratospheric aerosol injection, the technology most discussed here in this event, even according to its proponent, is in principle untestable. [There isn’t] any experiment that would give any meaningful information on the effect on the global climate with equal deployment in terms of scale and time frame.

In conclusion, what does that mean for the discussions on solar geoengineering governance? Many governments still remain highly uninformed about the issue, but some have taken a stand including to my knowledge, the African ministers for the environment who just recently in a decision called for a global governance mechanism for non-use of SRM. Those with vested interests in more research and experimentation have a disproportionate influence when it comes to sharing their expertise and exerting their influence and the biggest polluters have the least interest in transparency oversight and restrictive governance. That means, in our view, transparency alone would likely provide more legitimacy for those wanting to pursue technology development and outdoor experimentation.

We just simply cannot afford to waste decades of energy and resources on a high-risk untestable ungovernable hypothetical technology, especially when we know exactly what we can do today, and what we know works: phasing out fossil fuels, accelerating renewable energy, and cutting emissions to zero. I would welcome those interested in putting new options on the table or new tools in the toolbox, or getting all hands on deck for the major task at hand of phasing out fossil fuels, including supporting a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty as a new initiative.

For SRM, more than 450 scientists, which to me expresses a pretty strong emerging scientific consensus, are calling for a non-use agreement. More governments should join them. As with other dangerous technologies like nuclear or chemical weapons, we just cannot afford to remain neutral or walk some kind of middle way. We certainly don’t have time to wait for everyone to agree before setting a global precedent of precautionary and restrictive governance that can then pave the way for stronger multilateral agreements.

I actually think we know enough about solar geoengineering to say no today.

Q&A

Can you explain a bit more about the background of why UNEP undertook the assessment and about the methodology on how you choose authors and writers?

Andrea HINWOOD | I completely support that action must be maintained on mitigating greenhouse gas emissions to improve climate change projections. The reality is though we’re not acting quickly enough and we do have solutions and we should keep it. In terms of UNEP’s report, UNEP has a mandate at the outset to keep the environment under review, and we produce around 200 reports a year on a whole variety of topics. Those might be new topics, or they might be for a specific region or whatever; we don’t have resolutions for everything that we produce. When this topic came up, it was because there were so many voices coming up both pro and against SRM, and essentially we wanted to inform ourselves and the broader system as to what the issues were with solar radiation modification.

In terms of the selection of authors, we had a really hard time because there are so many conflicts of interest in this space because of where funding comes from. I would absolutely dispute the speculation on the views of the co-chairs, and I would suggest that perhaps you might want to have another consideration on that. I can say that across the panel members, there was a broad range of views and from completely opposed to those who were mildly supportive, and hence the report is what you have from a collection of experts in their fields contributing their scientific knowledge. I think we need to be very careful when we speculate on whether people are pro or against, which is why I think we need to be very neutral in this discussion and use the evidence base to help us. We absolutely need to keep the foot on the pedal.

With respect to climate change and no one is disputing that. The reality though is that there is research and substantial funding on foot in various parts of the globe. Personally, I don’t want to put my head in the sand and pretend that’s not happening. I want to actually tackle it, understand it, and so that there are good decisions that can be made by countries if they are faced with decision-making in a particular arena. This is why these fora are so good to discuss the issues. I think we should actually discuss it because it might mean we have an open transparent global conversation about it. In doing so, we might do dismiss SRM, and we go forth and actually solve the climate change problems. We may well in that process find solutions that we have not identified so far.

How did the Human Rights Council report come to conclusion that deploying SRM is higher than not doing it, given the limited knowledge we have now? The risk framework is about comparing the risk of doing and the risk of not doing in a quickly warming world. Different societies and cultures have different perceptions on risks, so is there not a need for a global discussion and consultation?

Patrycja SASNAL | The report by the Advisory Committee is based on the IPCC, and [comes out] as the six and a half pages, and not just what was presented today. I think that relates to what Francesca asked about, whereas it does not relate to the UNEP report because we do not really have time to engage with it.

I also think that the difference that there are differences of opinion and the aspects that we focus on because our report purely focuses on the human rights-based perspective. I just want to reiterate that our report recommends a ban on outdoor experiments of solar geoengineering. I don’t think there should be any doubt about that. Moreover, we think the fossil fuel nonproliferation treaty is in line with the human rights regime.

As for the question, how did we conclude that deploying stratospheric aerosol injection is more risky than not doing it? That sentence is not included in the report, but what the report says is that we know little, but what we know now is enough to come to a conclusion that it would be extremely dangerous to deploy stratospheric aerosol injection at a large-scale. This is common knowledge in literature today. I hope my co-panelists will correct me if I’m wrong, but all of them did say this. So it is absolutely noncontroversial to make the statement.

I also want to say that often people who are in favor to some extent be it to a small or to a large extent, base their opinion on what was written by Paul Crutzen, the Dutch chemist Nobel Laureate who indeed did write in Nature that we should research and explore geoengineering, meaning mostly solar geoengineering that is sulfur dioxide particles in the stratosphere. However, in 2014, a couple of years before he died, he did say that he would not apply it. He was in favor of research going on, and he said that he’s already surprised by how many pursue it as a research topic but he shared the fear that researching geoengineering would lead to an attitude that CO2 reductions can be postponed because sulfur injection technology will save us from dangerous climate change. That would be totally wrong, he said, and we should definitely not count on geoengineering.

This is just to underline the moral hazard risk, (a bad terminology, but it is what is in literature), and I think we’re sort of indulging in it, engaging in that risk right now. As we speak, SRM is a relatively simple technology and a relatively cheap technology. To know more about it would require research and who is to say in a critically thinking society with open minds to control or contract or limit research, no research indoor research. The question is about public money, about outdoor experiments. While we’re not cooking yet, the indulgence in thinking about a very risky and contrary to human rights solution is dangerous. All of our minds and resources should be on something else. That is my opinion if I can speak freely about what’s in the report is in the report.

To make something clear on the understanding of risk in the Global South, we can take it to the absurdity that as we sit around the table, we don’t understand the risk the same way. The Global South is a generic term – also very Eurocentric and colonial because there are many different voices in the Global South, as there can be different opinions. So we don’t know what the Global South thinks until we hear those voices. The point now and the goal is to hear as many voices around the globe as possible and not only us in the Global North.

Do we know enough already? Do we have all the information to make these key decisions?

Marie-Valentine FLORIN | We don’t know enough, but it is not the only domain in which we don’t know enough, although we have to take decisions. What we need is more inclusive deliberations, and more inclusion in the process by which a decision can be made.

I would like to remind everyone that there are two ways to elaborate legitimate decisions. First, when the decision is based on sufficient signs, this is normative evidence. Second, when the process is legitimate, as for example, in a democratic country where the citizens vote, it is legitimate even though it may be different from what another country would decide.

Moreover, to some extent, the context has changed the decision. We are no longer before the Paris Agreement; we are in the context of we know where to go. We know that current climate policies will not be enough so it is wrong to stay within that framework that we can hope to reduce CO2 emissions and to reduce atmospheric concentration sufficiently to avoid the crossing of dangerous thresholds. We have to be realistic that we are not on the path to sufficient climate change, and CO2 and greenhouse gas emission reduction. As such, the decision context for SRM is also changing.

One of the topics we have raised several times today is the Global South. We have also discussed the UNEA resolution back in 2019. One argument that we had at the time was that we need a report by UNEP because we have to inform all governments.

We know that not all governments have the same access to scientific institutions, so not all have the same capabilities to command, conduct studies, and so on. Our view was that one of the strengths of multilateral UN system is that they have the capabilities to involve scientists around the globe. The IPCC shows that there are ways to do that. The UN per se by definition can take different perspectives, which is why also we thought that UNEA would be the right forum to further look into these topics. How can the Global South best be involved?

Cheikh Ndiaye SYLLA | I agree with Patrycja that the definition of Global South is somehow not understood well: how can you compare the Global South and North? We are not speaking usually to the Global North but only to the Global South. What we have to do in SRM is to make sure that the implications of what we are doing are clear.

We don’t know the consequences [of using SRM technologies], which is why we ask to have a global study to make sure that all countries and stakeholders are involved. Any action we do to the atmosphere can have a large impact. With regards to the precautionary principle, it’s better to do some studies and to make sure that everything is on track and everybody understands where we are and where we are going.

Closing

H.E. Amb. WERTLI | It was very helpful to get this overview about these different reports that have been published. Those who have conducted reports have different backgrounds: there were UN institutions, own initiatives, scientific initiatives. We have also heard interpretations of what extent they come to similar or different conclusions. There were also interventions outlining that we have quite a lot of information already that would not prevent action regarding non-use agreements of SRM. Other views say clearly that we need more information and some research, in the context of a framework, where we would agree not to use those technologies but continue research on that to get a better understanding.

What was very much in common here was a strong call about the moral hazard problems. I think it’s a common understanding in this room is that any discussion about SRM should not reduce or in no way be used as an excuse to reduce efforts for mitigation and adaptation. That is really the basis for these discussions.

From a government perspective, we talk a lot about the Global North and South but such discussions are not easy for anybody to gain a full understanding about very complex technologies, both in terms of discussion and context. From our side, we can always say that we are grateful for good reports on those issues if they come from your institutions. For sure they have a special weight on that and this is always very helpful in elaborations.

Video

Live from International Environment House 2

Live in the Room

Photo Gallery

Links and Documents

- Presentations made during the event

- Climate-Altering Technologies and Measures

- One Atmosphere: An Independent Expert Review on Solar Radiation Modification Research and Deployment | UNEP

- Emissions Gap Report 2021 “ The Heat is on” | UNEP

- Reducing the Risks of Climate Overshoot | Climate Overshoot Commission

- International governance issues on climate engineering | EPFL