Event Conference

The Challenge of Warfare and War Zones’ Toxicity | Repairing Toxic Damages | Geneva Toxic Free Talks

22 Sep 2022

15:30–17:00

Venue: Centre Administratif de Varembé & Online | Webex

On the sidelines of the 51st Regular Session of the Human Rights Council, this year’s Geneva Toxic Free Talks took place over two days of conferences and discussions, celebrating 25 years of the mandate and the struggle for the right to live in a toxic free environment.

About the Geneva Toxic Free Talks

The Special Rapporteur on toxics and human rights reports every Fall to the Council and to the UN General Assembly on issues related to his mandate. The Geneva Toxic Free Talks aim to harness the opportunity of this moment of the year to reflect on the challenges posed by the production, use and dissemination of toxics and on how Geneva contributes to bringing together the actors working in reversing the toxic tide.

On the sidelines of the 51st session of the Human Rights Council, this year’s Toxic Free Talks took place from 21-22 September — two days of conferences and discussions, celebrating 25 years of the mandate and the struggle for the right to live in a toxic free environment.

About this Session

By definition war zones are marked by destruction. But we often forget that this destruction can reach a high level of toxicity and can have massive effects for a long time. Such effects then require a lot of means to be countered, leaving the populations largely destitute. Moreover, the production of weapons itself can generate a high level of toxicity, which can reach peaks when it comes to nuclear weapons. Finally, the circumstances of a conflict can lead belligerent states to suspend the fundamental rights of people with regard to toxic substances, creating a de facto situation that often persists after the conflict, thereby permanently suppressing these rights. How can such developments be managed and countered?

Speakers

Samuel K. Jr. LANWI

Deputy Permanent Representative of the Marshall Islands to the United Nations Office and other international organizations in Geneva

Guillaume CHARRON

Counsellor, Permanent Mission of the Republic of the Marshall Islands to the United Nations Office and other international organizations in Geneva

Nickolai DENISOV

Deputy Director, Zoï Environment Network

Diana RIZZOLIO

Coordinator, Geneva Environment Network | Co-moderator

Summary

Welcome and Introduction

Diana Rizzolio, Geneva Environment Network

This year’s Geneva Toxic Free Talks took place over two days with conferences and discussions celebrating the important milestone of the 25th anniversary of the mandate and the struggle for the right to live in a toxic-free environment. In this session, we discuss the challenge of warfare and the toxicity that comes along with it.

Yves Lador, Earthjustice

Yesterday, we celebrated 25 years of the mandate, the oldest environmental mandate of the Human Rights Council. Today, we are spending time exploring some of the issues that the mandate has already worked on. In the previous discussion, we talked a lot about legacy issues, such as how we deal with the dissemination of plastics? In this second dialogue, we also look at a different kind of legacy issues: conflicts, both old and ongoing. We will have an example with the Marshall Islands and another in the second part on Ukraine.

Marshall Islands: Nuclear testing, human rights and the environment

Samuel K. Jr. LANWI, Deputy Permanent Representative of the Marshall Islands to UN in Geneva

Even though the nuclear tests for which we have tabled resolutions on took place in the post-war period, it nevertheless can be considered as after-effects that can be seen in the environment of war zones that we are talking about.

The Marshall Islands were known to be the “Pacific Proving Grounds”, that were used as sites for nuclear tests “for the good of mankind”. These tests took place in a period of 12 years, between 1946 and 1958. To put it in context, the strongest of these was 1.5 times the Hiroshima explosion. This happened every day for 12 years, amounting to about 100 strikes in all. This all happened when we were under the transition of the UN Trusteeship, where we had to become a state, a real nation, but there was a lot of highly classified information regarding the reporting of the conduct of these tests. Moreover, published research have not been peer-reviewed, showing an underestimation of estimates of the tests.

In the draft resolution, we have discussed elements of transitional justice, of which the pillars are justice, reparations, guarantees of non-recurrence. We are looking for this to be an Item 10 resolution, Technical assistance and capacity building from OHCHR and the Council to help our national capacity to apply human rights on these issues.

There hasn’t been any recognition of the harm done and what we have suffered. As a member of the Council, we took the opportunity using our membership to share our story through this solution.

Some have already said this is a new issue for the Council and has questioned whether the Council is the right body to deal with human rights claims as part of its legacy. We respectfully disagree. The previous SR toxics has shown this in his report in his country visit to the Marshall Islands. Moreover, the mere fact that we are here having this conversation this afternoon with the SR and all the other stakeholders present, the cross-cutting issues and the links between toxics and human rights give us comfort.

The core group comprising of the Marshall Islands, Fiji, Nauru, Samoa and Vanuatu, have conducted visits and informals. We want more open dialogues, even if these are very difficult.

On 28 September, the core group has tabled a resolution in the Council requesting the UN human rights office to provide technical assistance and capacity-building to address the human rights implications of the nuclear legacy in the Marshall Islands (HRC/51/L.24/Rev.1).

Guillaume Charron, Counsellor to the Permanent Mission of the Marshall Islands to the UN in Geneva

To put things in context, in talking about explosions that are one and a half times stronger than that of Hiroshima, it also means that atolls and islands were completely pulverised into thin air. We have the disappearance of habitable land, and in addition, the remaining atolls have been severely contaminated that they’re now uninhabitable for thousands of years.

In addition, remaining atolls have been severely contaminated that they’re now uninhabitable for thousands of years. The entire population of all these islands has been displaced and is still displaced today, with very little chance to return and very little support. Apart from people from these areas who were directly affected, the whole country was affected, not only in terms of managing and providing assistance to those who have been permanently displaced, but the rest of the population itself is suffering from disproportionate rates of cancer that affects the rights to food, to water, to reproductive health. All these are directly impacting a country that has not carried out the tests, nor has the capacity to address such problems from a health perspective and a human rights-perspective.

On the environmental dimension. The United States, after the testing, placed the fallout and residue from the nuclear test in a dome that is hardly one metre above sea level, without tracking the return of the waste at that time in that room. In addition, there is also information circulating that some of the waste from the Nevada tests were placed there. That dome is leaking now and even if it wasn’t, there’s also water intrusion in an area where a lot of the world’s tuna fishing takes place. There is a direct contamination in the Pacific. It’s not something that a country, like the Marshall Islands, can address, nor cannot be held responsible for as they didn’t cause it, and are unable to mitigate it on their own. For example, the Marshall Islands is not able to monitor health and detect cancer rates in its own country, and only those who can go abroad are able to be treated.

There is also a clear problem with the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment in this situation. It affects the export of food products such as tuna: anything that passes through the sea in this area is contaminated, yet there hasn’t been any monitoring conducted to trace the toxicity being spilled out in the Pacific. Small island developing countries are extremely dependent on their environment for their development and sustainability, as there aren’t many alternatives in terms of land or resources. This has a direct impact also when considering sealand rights, which is likely to reduce even more the amount of land available for the population.

While the resolution focuses on the nuclear legacy of the Marshall Islands, there are other islands, regions and countries that have also been affected by unexploded ordnances since the Second World War, where the Marshall Islands do not have the capacity to clear and dispose of these. We need international assistance in doing so.

Response by Yves Lador, Earthjustice

What was described is an incredibly blunt, and one of the worst explicit denial of equality of rights. This is one of the very hot issues on decolonization, and definitely needs to be discussed in Council. I want to thank you for bringing this up, as this should have been discussed much earlier.

Response by Marcos Orellana, UN SR on toxics and human rights

The mandate on toxic substances and human rights has addressed these issues in the past. In 2007, my predecessors already produced a report on armed conflict and toxic substances (A/HRC/5/5), in 2012, one of my predecessors’ toured countries and made recommendations (A/HRC/21/48/Add.1), and in 2022, together with David Boyd, we published a report on the right to an environment free of toxic substances as a substantive part of the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment (A/HRC/49/53). This issue is not outside the work of the Council; it belongs directly to the toxics mandate as it relates to toxics.

Some believe that legacy issues are issues of the past, and that we have a current problem. “Why get stuck and not look to the future?” This is misleading, because when it comes to legacy toxic issues, the chemical composition of certain pollutants and toxic substances calls into question their persistence and latency… It’s not just situations that happened decades ago, but situations that have implications today. We may not be testing today, at least not in the same way as we used to, but the contamination is there, and it affects people. The impact of that contamination gets worse over time because of such latency and the problems get worse. They don’t get solved by themselves and therefore need to be addressed deliberately. The mandate is a tool to address them intentionally and deliberately.

The scope is quite broad. We’re looking at weapons, which concerns their manufacturing and the workers, the proliferation of contaminated sites, and in many countries, there is testing and the evidence put on the table is indeed compelling.

The issues of conflict that are ongoing or have recently been resolved and that have international dimensions, such as what’s happening in Ukraine, and internal ones. In an academic visit to Colombia, the issues of the legacy of the internal armed conflict and peace-building efforts are also on the table alongside the implementation of the peace accords between the State and the guerrillas at the time. In relation to this broad scope, this issue will continue to be on the agenda of the mandate. We will continue to reflect and explore ways in which the mandate can usefully inject its expertise and visibility.

War in Ukraine: Environment and toxic legacies

Nickolai Denisov, Deputy Director, Zoï Environment Network

The animation below shows the damage to industry and infrastructure, and the potential damage to the environment, during the War in Ukraine.

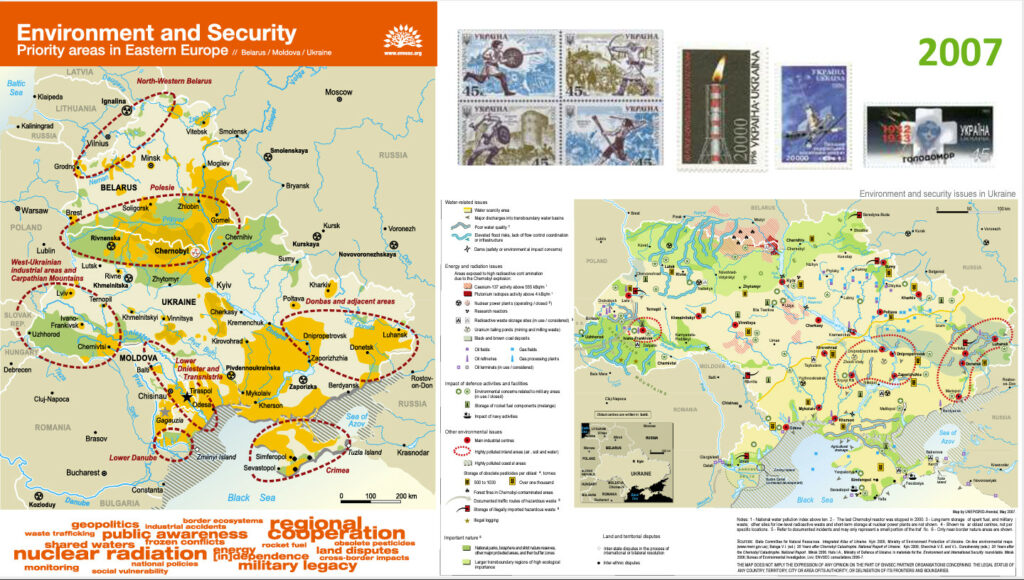

One of the initiatives of the Environment and Security Initiative was to map out the areas and dimensions where environment and conflict can potentially ignite, including the area in and around Ukraine. If you compare the map below from 2007 by the Initiative compare it with what we see today, the correlation is unfortunately quite strong. The map includes some of the things that were already at the time in the attention of the UN Special Rapporteur.

2014 Donbas war. Given Donbas is one of the hotspots identified in the beginning, we worked with environmental authorities to help strengthen environmental governance and monitoring. The trouble was the concentration of industry in Donbas which was at the time the most industrialized part of Ukraine, and even Europe, including coal mining. This was affected by the hostilities since 2014, including the mass-scale flooding of the Donbas coal mines, which was last seen during WWII. Impacts on the whole industrial infrastructure simply by massive disruptions and significant threats to the facilities.

There is a global dimension as well, such as the destruction of forests and air pollution, contamination of land and soil, potentially toxic waste spillages, access to natural resources, damage to ecosystems and capacities manage the environment. All this were seen in Donbas, and now it’s in a much larger scale.

War in Ukraine. We have recorded from open sources, at least 14,000 incidents of damage work to settlements, disruption of access to critical resources and disruption of normal work, in over 1,000 Ukrainian cities, towns and villages. As most of the incidents are related to direct physical damage, a qualitative assessment of environmental damage can also be done.

- Water and toxics: affected industries are directly connected to bodies of water, and affected wastewater treatment facilities can have a significant toxic impact on the waters.

- Fires and forests: the intensity of forest fires has increased, as it is 10x higher in Ukraine at the beginning of the conflict than it is outside of the conflict. It is 15x higher in specific forests, such as coniferous ones.

- Ammunition from mines also affect the environment.

The environment has become the silent victim that also needs our attention. Advocacy and communication are very important today. Attention is becoming satisfactory; we just need to keep it on the agenda. We need information, to communicate our actions.

The general idea is that Ukraine will need a recovery, which includes the environment: a recovery of Ukraine in an environmentally friendly way. It is very tempting to rebuild quickly, people need housing and Ukraine needs industry.

An example from an area around France would give sufficient warning, where the trench warfare in WWI was most intense left a lot of the legacy of the war in the soil around this area. It was formerly very agricultural before the war and now some of the areas are still classified as red zones, where you can’t undertake agricultural activities because you still have to get rid of the toxic chemicals that are still in the land. This is unfortunately what we probably must expect for Ukraine. It will take decades, if not several, to clear some areas until they are usable again. With Ukraine as one of the breadbaskets of Europe, the toxic impacts of this war will be on the global agenda for years and decades to come.

Response by Marcos Orellana, UN SR on toxics and human rights

At the beginning of the war, a number of special procedures issued a statement that referred to the kind of issues we are talking about today. In the toolbox of tools available to deal with these issues, one looks at prevention, the kinds of monitoring and reporting, information gathering, awareness raising and visibility that comes out of the work of society, that can help with prevention, with weapons designed, with the conduct of hostilities, to see what is happening on the ground. These have implications for what comes after.

Nickolai was talking about recovery, about possible compensation, and this made me think of a subject that is often discussed in international environmental law in relation to human rights and armed conflict: the experience of the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and the resolutions adopted by the Security Council setting up an international compensation commission whose mandate included ensuring compensation for environmental damage. In this case, given the composition of the permanent members of the Security Council, such a commitment by this UN body seems highly unlikely. The question that arises is what kind of tool could be mobilised to ensure access to a remedy for those who have suffered from environmental contamination and, more generally, for communities and the country.

In this debate, the focus has often been on armed conflict and the environment. But the issues are broader than that. There is pollution resulting from conflict, contamination, among others. Earlier, we heard from the Marshall Islands about unexploded munitions which needs monitoring. There are many things that come together and it is not just about environmental protection in terms of armed conflict. It is the broader holistic situation of the country’s environment during the conflict that is not the same. International environmental instruments have been developed to address the militarisation of the environment, best known is the Environmental Modification Convention that was heavily influenced by the use of Agent Orange by the US during the Vietnam War. These instruments focus on the use of the environment as a tool of war: getting benefits by blowing up hydroelectric dams for example.

This is a small part of the puzzle. If we look at the International Criminal Court, in its jurisdiction, we see that war crimes have taken this body of law and incorporated crimes where environmental destruction is widespread and unnecessary. The question is whether this body of law is sufficient to deal with the broader issues that we have seen. There is a recent document from the International Law Commission that has been submitted to the principles on armed conflict and the environment has submitted principles to the General Assembly for consideration, which included a principle on toxic remnants of war.

Conclusion

Marcos Orellana, UN SR on toxics and human rights

All the issues discussed over the past two days can be covered by the right to a non-toxic environment, the right of everyone not to be exposed to hazardous substances. These are key elements of the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment. We see this when we talk about the challenges of implementation. There are still challenges to better understand the realities in which these rights operate to improve the standards needed to address them and provide real protections for people.

To address this, human rights cannot be absent from the conversation, and are integral to legitimate and effective solutions to address the detoxification of the planet and the disastrous consequences it has for so many people around the world.

There is plenty of time in September and next year to identify a range of issues that we can work on, but in the meantime, the mandate has an open door. We are ready to engage with all of you, with those of you who are online. I encourage you to get in touch with the mandate. Send us information, send us communications and let’s explore how we can work together.

Video

Key Messages

With testing that occurred in post-WW2 near Marshall Islands, Samuel K. Jr. Lanwi of @RMIGeneva the #nuclear testing blasts were felt everyday for 12 years, with #toxic effects being felt up to today.

The draft resolution being tabled next week hopes to tell the story. pic.twitter.com/m8ZD2L5jNs

— GENeva Environment Network (@GENetwork) September 22, 2022

Photo Gallery

Documents

- Presentations made during the event

- Legal framework related to the release of toxic and dangerous products during armed conflict (A/HRC/5/5) | SR toxics and human rights | 2007