Event Virtual

Conservation NGOs at Risk

This virtual event, launching a new publication, was organized by the University of Geneva, IUCN CEESP, and the Geneva Environment Network, in parallel to the 49th Session of the Human Rights Council and in the run-up to the Convention of Biological Diversity resumed sessions of the twenty-fourth meeting of the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA 24), the third meeting of the Subsidiary Body on Implementation (SBI 3) and the Openended Working Group on the Post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (WG2020-3), to be held in Geneva, from 13 to 29 March 2022.

About this Session

One week before the critical global gathering to hammer out a new global biodiversity agenda in Geneva, a new report, Conservation NGOs at risk: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and shrinking environmental civic spaces, by the University of Geneva stresses the shrinking civic spaces, deteriorating conditions and attacks faced by conservation NGOs across the world. Based on a global survey and wider consultations with the NGO membership of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the report sheds light on the wide-spread patterns of both individual and organizational risks encountered.

At a time when the biodiversity conservation crisis is deepening, a silent crisis of NGOs struggling with harassment and shrinking spaces needs urgent attention. Building on on-going work to Geneva Roadmap 40/11 in support of environmental defenders, the report underlines the importance of enabling environments to secure effective and equitable conservation. This one-hour launch event presented the key findings by the author followed by hands-on perspectives from multiple NGO expert perspectives from around the world.

Speakers

Peter Bille LARSEN

Senior Lecturer and Researcher, Environmental Governance and Territorial Development, University of Geneva

Diana NABIRUMA

Senior Communications Officer, African Institute for Energy Governance (AFIEGO)

Liliana JAUREGI

Senior Expert Environmental Justice, IUCN Netherlands

Ruben KHACHATRYAN

Founder & CEO, Foundation for the Preservation of Wildlife and Cultural Assets

Úrsula PARRILLA

Regional Director for Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, IUCN

Delfin GANAPIN

Global Leader - Governance Practice, WWF International

Kristen WALKER

Chair, IUCN Commission on Environment, Economic and Social Policy (CEESP)

Yves LADOR

Representative to the United Nations in Geneva, Earthjustice | Moderator

Summary

Presentation of Key Findings

Peter Bille LARSEN | Senior Lecturer and Researcher, Environmental Governance and Territorial Development, University of Geneva

Overview

- This is a research report that speaks to the conservation community as a whole. This point to the challenging realities that conservation NGOs are facing. It’s important to recognise that they face new forms of legislation and violence.

- Recognising the scale and depth of civic space problems, we are good to talk about the biodiversity crisis, yet less good at talking about the silent crisis faced by many Conservations NGOs.

- There is considerable work in the Geneva Roadmap 40/11 and elsewhere to recognise environmental defenders at risk of being killed. But it is only the tip of the iceberg. There are other challenges and forms of violence, shrinking civic spaces that NGOs are facing.

Key findings

- By engaging with IUCN, the foremost global network of conservation of nature with over 1,400 members in over 170 countries, global survey and interviews with NGOs were conducted at regional conferences. The result: conservation has become less safe, according to over a third of NGO respondents.

- Civic spaces are rapidly shrinking.

- Policies, governing NGO and indigenous peoples’s action, such as more red tape, registrations and processes, have become more restrictive within the last 4 years. (50% of respondents)

- No regions are spared, yet challenges differ.

- There is a trend of increasing threats and violence.

- 50% think that threats and violence against NGOs are on the rise.

- 50% of respondents in Easter Europe, North and Central Asia report having experienced personal threats, physical violence or intimidation.

- With one in two NGOs facing such threats, these reflect how it’s no longer safe to do work in conservation.

- Conservation, IUCN-style, has become hazardous.

- This is not limited anymore to usual suspects, such as mega-projects, extractive industries and timber mafias. Work on species, wildlife trade and protected areas are also targeted.

- Policies of the IUCN, particularly of those related to social equity, gender equality, and human rights, have become taboo in other countries, making it difficult to uphold such standards.

- This is a silent crisis.

- There are clear signals of deteriorating conditions among partners: safety issues, surveillance, criminalization and even worse.

- New regulatory restrictions for NGOs and changing funding conditions are now present as well.

- This makes it ever more difficult to raise sensitive issues.

Time to act

- It’s time to act. The report points to the massive scale and the nature of the problem. Attacks against defenders are not isolated cases but are part of a structural crisis. There are common patterns of attacks against individuals and organizations.

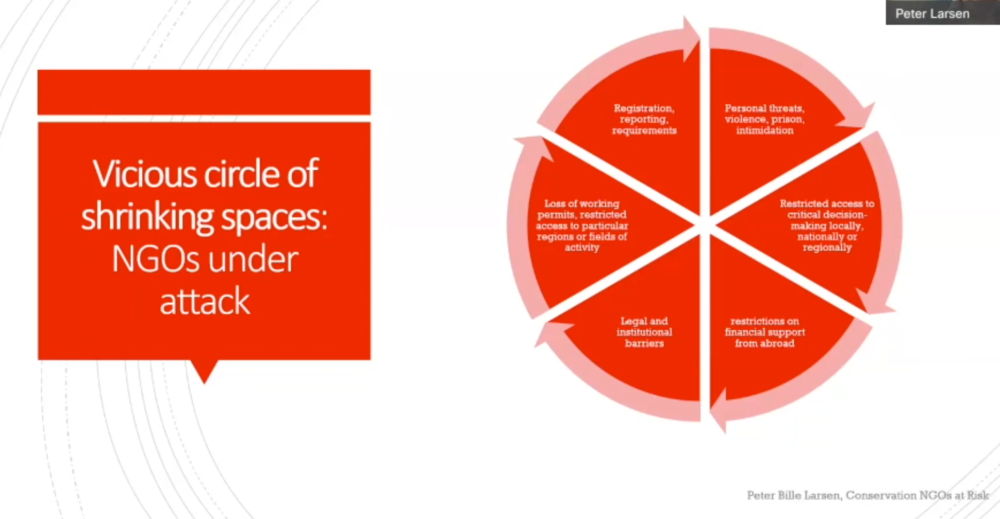

- There is a vicious circle of shrinking spaces where NGOs are under attack.

- All parties are also targeted: not only IUCN members, but scientists, partner organizations and communities, indigenous peoples and local communities, and public officials.

- Beyond the safety issues, how can we even expect to make a conservation difference if people and organizations are at risk?

- We need to reinforce environmental rights, enable civic spaces and build accountability: from fire-fighting to addressing root causes and an urgent need for policy to reinforce safe and enabling environments.

- IUCN as a union can be a space of solidarity as they can convene and mediate among members.

- They can help deal with threats and intimidation to personnel and organizations. They can also mobilise members and regional offices to monitor and give support to partners.

What can be our goals and targets?

- Halting biodiversity loss is an illusion without securing enabling spaces for conservation NGOs.

- There is an urgent need to boost IUCN, the world’s oldest environmental democracy.

- We need a post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework with space for organizations and individuals who stand up for biodiversity.

Global Round-table Perspectives

Diana NABIRUMA | Senior Communications Officer, African Institute for Energy Governance (AFIEGO)

- I would like to thank Peter for the report because while civic spaces are shrinking, the issue is under-discussed. And yet, we cannot work without civic spaces becoming what they ought to be.

- Sharing our experience in Uganda, I would like to show how civic spaces have already undermined the work of conservationists in Uganda, through the eyes of our organization, AFIEGO, a Uganda-based NGO that is also a member of IUCN.

- The conservation work. Just before the IUCN World Conservation Congress 2021 in Marseilles, AFIEGO worked with their partners on pushing for a recommendation to avoid extractive activities in protected areas made in the 2016 Congress to be implemented in Uganda. We decided that we need to, first, engage with the Ugandan government to point out that the recommendation was not being implemented, and second, if there is failure to act in Uganda, they will escalate it to the IUCN.

- Repressed civic space. To create such a letter, we need other IUCN members in Uganda and in Africa to sign it. Unfortunately, the civic space in Uganda is repressed due to bad laws that undermine our work: intimidation, arrests, detention, surveillance, among others. When we tried to mobilise Ugandan IUCN members to sign the letter to the government, it was very difficult. Members would get back to them saying that though the letter is in good faith, they are afraid as they sit in committees with the government, and that there are crackdowns going on.

- Government response. We sent the letter to the IUCN, but with more signatories outside of Uganda. Between May and October 2021, because we at AFIEGO are outspoken against the conduct of extractive activities in protected areas, we placed more pressure on the government. They responded by trying to close the organisation using the law. When that did not work, arrests were made seven times. It was a horrible experience that was meant to create fear and make us stop the work that we do.

Liliana JAUREGI | Senior Expert Environmental Justice, IUCN Netherlands

How does shrinking civic space undermine nature conservation efforts?

- We have seen from members on the ground how intimidation and violence have created an atmosphere of fear and self-censorship. Some forms of intimidation include: CSOs being unable to register as NGOs or receive funding due to legal restrictions; frozen bank accounts; and intimidation towards members of local partner organizations.

- Some groups, particularly women, are more affected than others by the shrinking civic spaces. There are laws halting the right to free expression and press under protectionist tags (such as the Anti-Terrorism Act in the Philippines). Countries with high biodiversity and large tropical forest areas have either a repressed or narrow civic space.

Lessons learned

- Conservation NGOs are not used to go out and connect with others. It was a learning curve to speak to human rights organizations and UN bodies to strengthen the support.

- We need to periodically analyse and reflect upon civic space context upon which the projects are being implemented.

- We need to have flexible emergency and contingency funds, and trainings on safety and security.

- Overall, we need to acknowledge and include civic space-related interventions into programs.

Example

- We included civic space change pathway in Green Livelihoods Alliance (GLA) program theory of change.

- The change enables partners and us to have a continuous monitoring and evaluation on civic space.

- It gives room to anticipate risks and enables partners to prevent and mitigate threats.

- It contributes to an adequate enabling environment for other project interventions.

- It allows use of funding for enabling an open and safe civic space for partners.

- This is a more systemic way of designing programs that not only allows us to achieve better results, but support a more sustainable way of working in conservation today.

Ruben KHACHATRYAN | Founder & CEO, Foundation for the Preservation of Wildlife and Cultural Assets

- Within Armenia, it is not necessarily corruption with the government, but corruption with international organizations working in conservation in the country that has become a huge problem and is continuously growing. This is why the report is one of the opportunities to share the stories of an IUCN member.

- The problem. It may not be visible from first glance, but from within the country, you will find that there are cases wherein certain international organizations are involved with wildlife traffickers, oligarchic structures and non-regulated hunting facilities. When you go against them, they can organize a huge campaign to counter it through media, blackmailing, personal threats, and blacklisting the organization in different circles of the organization.

- Armenia is a small country, but there have been many changes. With government changes, these groups are able to find the opportunity to continue corrupt practices, not only making it difficult to uproot the corruption, but allows them to become bolder and stronger in their practice.

- The work. As such, this initiative is very much needed in such cases like ours. Recently we lost one of our cases to an oligarchy on a special conservation area we’ve been fighting for in the last ten years. But we are strong, we will fight until the end.

- I don’t know where to address these issues, as it is not obvious on the legal front or the through the media that international connections are wide and deep. I think IUCN can be the right umbrella to understand and address these issues in order to protect organizations that work on the environment.

Úrsula PARRILLA | Regional Director for Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean, IUCN

- Even though this topic has been a subject of discussion in recent years, this report really puts the Union’s fundamental principles in the spotlight, hearing threats and intimidation straight from the members and showing the challenges in fulfilling commitments back home.

- The Union’s mission can only be fulfilled when every member can work and thrive in an enabling environment.

The situation

- The undeniable findings are deeply concerning, and these are only reflections of a wider structural problem that organizations, particularly in Central America, are facing. If these are the realities that organized civil society members are facing, one can only imagine the vulnerable situation in which grassroots organizations and individuals find themselves in.

- The number of environmental defenders that are dying, especially in these regions is increasing. The shrinking spaces are not only related to conservation matters, but are faced by most of the voices in society that raise issues of human rights related to sexual orientation, religion, race, gender, access to justice, freedom of speech, political association, and so on. This situation has also been aggravated by using COVID-19 as an excuse to suppress limit civic spaces.

- Acknowledging the threats and situations organizations are facing is the first step towards a transformational change and positive advocacy. In the report, IUCN becomes more relevant than ever. The findings should become a catalyst for action. It is essential that the Union prevails in realizing and adapting to the new context and demands of today.

- Strengthening rule of law may be possible through enhancing our work and interventions throughout the Union, particularly through the three pillars: developing trainings in support in legislation and enforcement, raising awareness and knowledge, and reinforcing the rights-based approach in all its interventions.

Reversing the tide

- I want to recognize the value of the IUCN as a convening space. The report shows how this remains one of most valuable characteristics of the Union as it can help start reverse the tide.

- One example on how this has happened. For one, in the region, the IUCN regional committees from Latin America and the Caribbean with the support of IUCN CEESP have harnessed a collective response aimed to promote and inform about the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters, also known as the Escazú Agreement, which has come into force after the 12th state ratified it.

- The way forward in implementing this agreement is still a long way and will be full of challenges. But it is a light of hope to provide a legally-binding framework where such threats can be made visible, and those threatening can be held accountable. IUCN members are playing a catalytic role in the region.

- We need to take this collective response into action: “No chain is stronger than its weakest link.”

- Guaranteeing that all IUCN interventions integrate the rights-based approach, and that no initiative led by governments, private sector, and others can be called a Nature-based Solution if its principle is not fulfilled. It is only a minimum requirement, but it is an important step forward.

Delfin GANAPIN | Global Leader – Governance Practice, WWF International

- I would like to use the minutes in order to discuss what follow up actions we, the IUCN, similar international organizations and people working in conservation, can do in response to this report. I would like to propose four practical actions.

What actions can we do to follow-up on these?

- Political-ecology assessment

- When you dig deep into the political-ecology of decision-making, you will find a logic behind it. As such, it would help to have a political-ecology of the issue, particularly when it comes to IUCN.

- What strikes me when our proposal to have this discussed during the World Conservation Congress in Marseilles was rejected, was what could the possible reasoning be behind it?

- I asked myself, what percentage of the membership of IUCN are powerholders in government? The appetite to take risks are going to be low or high depending on how much power they hold.

- In discussions with other environmental ministers, they mentioned that they are not the powerholders. Most of the time it’s the ministers of finance or with the president. We have to know the power situation of members of the IUCN, if we are to get it to dig deeper and be more involved.

- Global code of conduct

- The report already proposes a global code of conduct for environmental NGOs and defenders, but it is also important to have a code of conduct, a list of red lines, for the governments and corporations.

- We are struggling with this now. As we try to embed human rights in conservation and to commit ourselves to not working with governments and corporations that are violators of or non-committers to human rights, how do we discuss such sensitive matter with them? What’s the process in having these sensitive discussions?

- ‘Menu’ of actions

- In our anti-corruption work, a lot of actions that could be taken straddles from the low-risk to high-risk. We can get organizations to choose from a ‘menu’ based on the risk they are capable of handling.

- Action must be done, even at the low-risk level. By providing a menu, everyone has a chance to get involved and become contributors to solving the problem.

- Working group

- As mentioned in the report, it is also beneficial to have a working made up of IUCN members and external experts in this work that will follow up on the actions being taken. Such experts should also have experienced and taken the same risks, as such experience from the grassroots is important.

- Forming this group and having this analysis with the IUCN will have to provide solutions and frameworks for both the short-term and the long-term.

Kristen WALKER | Chair, IUCN Commission on Environment, Economic and Social Policy (CEESP)

How do you see the role of the IUCN in following up on the findings of the report?

- We are at a crossroads: we are not achieving our targets in terms of protecting the planet and at the same time, the people and communities are struggling to meet their own needs and fight for their own lands and territory. We need to think about doing things differently.

- CEESP has been the “rabble-rousers” within the Union, trying to bring the social dimension to the broader context.

- At the IUCN Congress, the Commission launched a Reimagine Conservation campaign to bring these conversations together in a much more public way. We have heard about environmental defenders in the forefront, such as in the Amazon, but we don’t hear enough about the struggles that many NGOs are facing. It’s often not talked about at the level that it should.

- The IUCN resolutions are available. We need to look at how they are being implemented and who we bring to the table to look at the implementation, highlighting Resolution 115 that looks at protecting environmental defenders and whistleblowers, and how we move this forward into a larger discussion.

What to do next?

- Bringing these issues to the Council. The regional work has already been highlighted, but the question is how we bring these conversations together. We can use the idea of Reimagine Conservation as a much broader platform to discuss these issues, bringing together many members to talk about these.

- As a Councilor, I commit myself to raising this in the IUCN Council, when we meet in person in May and during our retreat.

- Task force. I welcome Delfin’s proposal to form a group or task force that will look at these issues, that are composed not only of Commission members but members and secretariats, so that we can begin to work on the findings. I will follow-up with Urusulá and Delfin on these.

- Follow-up report. I also like the idea of potentially working with other collaborators through the Commission to work on a political-ecology assessment.

- What we also need to do and what we’re launching through the Commission are the Reimagine Labs: an opportunity to bring groups together to look into problems that we are trying to address, and looking at new ways to address them. It would bring skills from across the Union.

- If we are able to bring members together to think of new ways of how to address these new inwards, then we can bring these together in a follow-up report.

Conclusion

Yves LADOR | Representative to the United Nations in Geneva, Earthjustice

- On issues of following-up.

- There has been a resolution (HRC/RES/40/11) in 2019 at the Human Rights Council, adopted by the whole of the Council for the protection of environmental defenders. There is also roadmap as a follow-up mechanism.

- We now see how important it is to build on that, and not just leave these instruments behind. This is why the IUCN resolution is such an important milestone that also needs follow up.

- Thank you for the contributions made in this panel.

Peter Bille LARSEN

- The strength of the Union is in coming together when we have the Secretariat, the Commissions, the Members speaking up to bring this forward. I extend my gratitude to you for doing exactly that, saying we can raise this.

- Speaking to the time issue, this will be a long-term commitment. But the very practical suggestions brought to the table show a lot of promise and hope.

- I hope that we can do these both in an IUCN context and to bridge it to the human rights context, as well as the CBD negotiations. Let us not shy away from finding spaces to highlight these, to show there’s a way forward.

Video

Documents

- Conservation NGOs at risk: The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and shrinking environmental civic spaces | University of Geneva | February 2022

- Invitation

- Presentation

Links

- Geneva Roadmap 40/11 for Environmental Human Rights Defenders

- Resolution 115/Motion 39: Protecting environmental human and peoples’ rights defenders and whistleblowers | IUCN World Conservation Congress 2021

- Towards the Convention of Biological Diversity Resumed Sessions of SBSTTA-24, SBI-3 and WG2020-3

- Environment @ 49th Session of the UN Human Rights Council

- The Geneva Roadmap: supporting environmental human rights defenders | University of Geneva

- The Escazú Agreement, Human Rights and Healthy Ecosystems Dialogue Series | UNDP | 2022

- Conservation is becoming more dangerous: increasing violations and threats | IUCN | 16 March 2022

- Thinking together: a new report explores possible futures for conservation NGOs | Luc Hoffman Institute | 16 March 2022

- Geneva Roadmap 40/11 | Environmental Human Rights Defenders | Milestones and Opportunities in 2021 | HRC46 Side-event |9 March 2021

- The Environmental Human Rights Defenders Crisis: Towards a Geneva Road Map | HRC43 Side Event | 27 February 2020