Événement Virtuel

Plastic Waste in Mountains | Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues & International Mountain Day 2021

10 Dec 2021

11:00–12:30

Lieu: Online | Webex

Organisation: Geneva Environment Network, Conventions de Bâle, Rotterdam et Stockholm, Norvège, Suisse, Center for International Environmental Law, Forum on Trade, Environment & the SDGs, Union Internationale pour la conservation de la nature

The Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues aim to facilitate further engagement and discussion among the stakeholders in International Geneva and beyond. In addition, they intend to address the plastic crisis and support coordinated approaches that can lead to more efficient decision making. This session was held on the occasion of International Mountain Day. (Photo ©Jason Sheldrake)

About the Dialogues

The world is facing a plastic crisis, the status quo is not an option. Plastic pollution is a serious issue of global concern which requires an urgent and international response involving all relevant actors at different levels. Many initiatives, projects and governance responses and options have been developed to tackle this major environmental problem, but we are still unable to cope with the amount of plastic we generate. In addition, there is a lack of coordination which can better lead to a more effective and efficient response.

Various actors in Geneva are engaged in rethinking the way we manufacture, use, trade and manage plastics. The Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues aim at outreaching and creating synergies among these actors, highlighting efforts made by intergovernmental organizations, governments, businesses, the scientific community, civil society and individuals in the hope of informing and creating synergies and coordinated actions. The dialogues highlight what the different stakeholders have achieved at all levels, present the latest research and governance options. In addition, the dialogues encourage increased engagement of the Geneva community in the run-up to various global environmental negotiations, including UNEA-5 in February 2021 and February 2022.

Building on the outcomes of the first series of dialogues and the recent policy developments, the Geneva Environment Network is hosting a second series of events to facilitate further engagement and synergies on tackling the plastic crisis. These events are held in collaboration the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions Secretariat, the Center for International Environmental Law, the Global Governance Centre at the Graduate Institute, IUCN, Norway, Switzerland, and the Forum on Trade, Environment & the SDGs (TESS).

About this Session

While much attention in recent years has focused on the impacts of plastic waste on the world’s oceans, pollution in mountain regions has rarely made the headlines. Meanwhile, plastic is the most common type of waste found in mountains. The rapid increase of plastic waste in these region is drive, to a large extent, by tourism. While tourism is an important source of income especially for developing countries, its plastic waste footprint tends to far exceed that of local populations, thus becoming high priority for those countries. Adding to the plastic waste burden that mountains are already shouldering, is the spread of microplastics, which travel long distances and often end up on mountains like the Tibetan Plateau, the Alps or the Rockies.

Meanwhile, mountainous regions face specific challenges in addressing plastic waste due to their remoteness, limited access to human and financial resources, lack of economies of scale, and challenging natural conditions. Many mountainous regions, especially in developing countries, have limited capacity and infrastructure to prevent the generation of plastic waste and ensure its environmentally sound management. This often leads to open burning and dumping.

Yet, success stories and innovative approaches exist and are already being implemented across the world, including the remotest mountains: Garbage declaration and clearance systems for mountain expeditions, community-run collection centers, recycling of bottles into ponchillas, engaging mountaineers in cleanup operations, and full-cycle infrastructure for waste-sorting and management in national parks.

Ahead of the International Mountain Day, celebrated on 11 December, this dialogue provided an opportunity to put mountains in the spotlight of the global efforts to address plastic pollution. It served as an opportunity to present the key conclusions of a draft report being finalized under the project Plastic Waste in Remote and Mountainous Areas (financed by the Governments of Norway and France), captivating findings of the 2021 Global Mountain Waste Survey, 10 steps to be a Mountain Hero and compelling insights of mountaineers. The speakers addressed the following topics:

- Drivers and status of plastic pollution in the mountains

- Challenges faced by mountain communities in managing plastic waste

- Local, national and global success stories in plastic waste management in the mountains

- The role of mountaineers in tackling plastic waste

- What individuals and communities can do for clean mountains

- Recommendations to strengthen plastic waste management in the mountains

Speakers

By order of intervention

Damaris CARNAL (Moderator)

Switzerland’s Focal Point for United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

Patrick UMUHOZA

Multilateral Cooperation Officer, Advocacy and MEA Monitoring Unit, Rwanda Environment Management Authority

Björn ALFTHAN

Senior Expert, GRID-Arendal

Jost DITTKRIST

Programme Officer, Secretariat of the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions

Leif Inge MAGNUSSEN

President, Environmental and Sustainable Access Commission, International Federation of Mountain Guide Associations (IFMGA)

Carolina ADLER

President, Mountain Protection Commission, International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (UIAA) | Executive Director, Mountain Research Initiative (MRI)

Lesya NIKOLAYEVA

International Environmental Expert

Matthias JUREK

Programme Management Officer, Vienna Programme Office – Secretariat of the Carpathian Convention, Europe Office, UNEP

Video

In addition to the live WebEx and Facebook transmissions, the video is available on this webpage.

Summary

Opening Remarks

Welcome and Introduction | Diana Rizzolio, Geneva Environment Network

- The Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution dialogues aims to keep the international community in Geneva and beyond engaged on the topic and make links with numerous international processes to tackle plastic pollution, and with the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA). These dialogues are organized by the Geneva Environment Network in collaboration with the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions Secretariat, the Center for International Environmental Law, the Global Governance Centre at the Graduate Institute, IUCN, Norway, Switzerland, and the Forum on Trade, Environment & the SDGs (TESS).

- While much attention in recent years has focused on the impacts of plastic waste on the world’s oceans, pollution in mountain regions is more rarely making headlines. Plastic is the most common type of waste found in mountains and the main origin is tourism.

- We also highlight, as discussed in a previous session of these dialogues held exactly one year ago, that airborne micro- and nano-plastics are transported in the more remoted places of this planet, including on mountains.

- Discussions on plastics in mountains at GEN started back in 2018, the year when UNEP started putting in more resources to beat plastic pollution. Held at the International Environment House in Geneva, a roundtable on plastics in the mountains somehow led to the project Plastic Waste in Remote and Mountainous Areas Project. In fact, some of the panelists today were physically present in the session 3 years ago.

Broader Context and Objectives of this Session | Damaris Carnal, Switzerland’s Focal Point for UNEP

- Plastic pollution is a global challenge that will require a comprehensive and coordinated action. Engagement of all is needed: governments, international organizations, business, and civil society. The panel today allows us to great perspectives.

- Much of the impact is still focused on the impacts of plastic waste on the ocean, while pollution in mountain regions is not often discussed. Plastic pollution affects all compartments of the environment, and 80% of plastics in the ocean come from land-based sources. As such, we need to develop a comprehensive life-cycle approach if we are to tackle this issue properly.

- Plastic is also the most common type of waste found in the mountains. Microplastic pollution has also been found in the snow close to the peak, for example, of Mount Everest. Urbanization and tourism have been some of the main drivers of plastic waste, adding to the challenge.

- Dealing with plastic waste is a challenge for all countries, but mountainous regions face specific ones in addressing them due to harsh climate, remoteness, limited land availability for waste treatment and disposal, and at times, weak infrastructure.

- Many mountainous regions, particularly in developing countries, have limited capacity and infrastructure to prevent the generation of plastic waste and management. It then makes collection and safe disposal more challenging than in the urban lowlands. Another challenge is the data gap on the types of waste being generated, making it difficult to know the problems and bottleneck specific to waste management in mountain areas. Today we’ll hopefully learn more.

- Many initiatives, projects and government responses have been developed, but we’re still unable to cope with the amount of plastic we generate. There is also a lack of coordination at the global level that would allow us to have a more effective and efficient response.

- This is why Switzerland is supporting the launch of a process to develop a legally binding instrument on plastic pollution at UNEA 5.2 at the end of February next year. Such an agreement should have a life-cycle approach, across different compartments and streams.

- However, negotiating a treaty will take time and won’t solve everything. Discussing initiatives and projects that deal with the issue are therefore critical. What do we know about the challenges? What can we do about them?

Plastic Waste in Mountains – From Challenges to Solutions

Addressing Plastic Waste in the Mountains – a Developing Country’s Perspective | Patrick Umuhoza, Rwanda Environment Management Authority

- We can only beat plastic waste by joining hands as international community and establish a specific tool such as a binding agreement that will direct them with the common understanding and actions, as Rwanda and Peru have already started paving it through a draft resolution on an international legally-binding instrument on plastic pollution.

- Biodiversity has no voice, but we can advocate for it as it is part of our life. Single-use plastics corrupted companies and people’s mind up to the extent that they are not interested in looking for alternative to them.

- Since 1986, Rwanda joined hands with international community through ratification and accession of different multilateral environmental agreements (MEAs). In 2003, living in a clean and healthy environment became a constitutional right for each Rwandan citizen. After finding out that plastic carry bags are enemies to clean and health environment, we started thinking, “What can be done to ensure that the right is protected?”

- In 2008, Rwanda adopted the law prohibiting manufacturing, importation, exportation and use of plastic carry bags. This was a strong decision taken, as they became a primary tool for our citizens. Political will and awareness raising on the negative impact of plastic carry bags are the weapons of success which led to the country’s behavior change. In 2019, Rwanda amended the law and included the single use plastics. Today no one is allowed to import, export, manufacture and use plastic carry bags and single-use plastics in Rwanda.

- It’s been two years ago since plastic bags have been banned in Rwanda but are still seeing plastic waste in remote areas and mountains. This proves the gravity of how plastic wastes are burdening our environment. However, REMA in collaboration with global community and authorities, organizes community works as a homegrown solution to a clean environment, including mountain and remote areas. People come together and collect all plastics in selected areas and use such opportunity as an awareness raising tool on banning importation, exportation, manufacturing, use and sales of plastic bags in Rwanda. I think that having laws in place are better and their enforcement is paramount.

- We are facing different challenges that require us to work in extraordinary way to ensure that the proper enforcement of all instruments in place. One person cannot win this battle alone. Countries are required to join hands and work together to protect and save our common mother through efforts with national policies and other key institutions. They are helping us carry out regular inspections in different supermarkets and shopping malls. Beverages companies with no alternatives were given a fixed grace period and are obliged to look for alternative to single use plastics. Regarding the proper management of plastic waste generated by those companies, an environmental review is imposed to enable recycling companies to collect and recycle the generated waste.

- Having a mountain and biodiversity cleanup does not make Rwanda safe from plastic waste pollution. Environment has no borders; global effort is needed. I cannot conclude without saying that developing countries have become the dump site of the developed country due to unfair and international trade. Women and children from poor families don’t have a choice must risk their safety to make living and provide for their families due to the millions of tons dumped in Africa. We don’t have capacity to recycle and reduce them. Most of plastic wastes are dumped in a mountain or remote areas and some people choose to burn them which is highly hazardous to human health and the environment.

- We cannot turn our clock back to the society that survives without the use plastics but today we have the power to shape the future that is plastic free. Let’s start now, our behavior matters. if you can’t use it, please refuse it and save a mountain from being the dumpsite of plastic wastes.

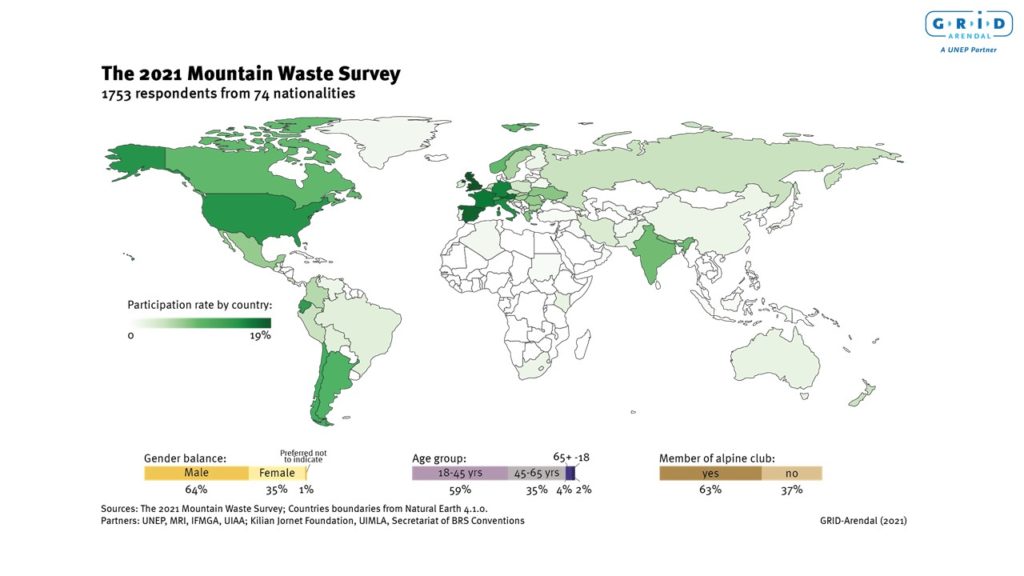

Results of the 2021 Global Waste in the Mountains Survey | Björn Alfthan, Grid-Arendal

- In the global survey ran on waste and mountains, we surveyed mountaineers and other mountain enthusiasts in the world. What was found was that though there was a lot of attention in a few sites (such as Mount Everest), data on what was going on around the world was not available.

- In the map of the survey of over 1,700 respondents, majority of them came from Europe and from North America with good participation from South America and from Asian countries of India and Nepal. Unfortunately, there weren’t as many responses from the continent of Africa, which is something to bear in mind.

- Majority of respondents were members of alpine or mountaineering clubs. Roughly two-thirds to one-third were also male respondents.

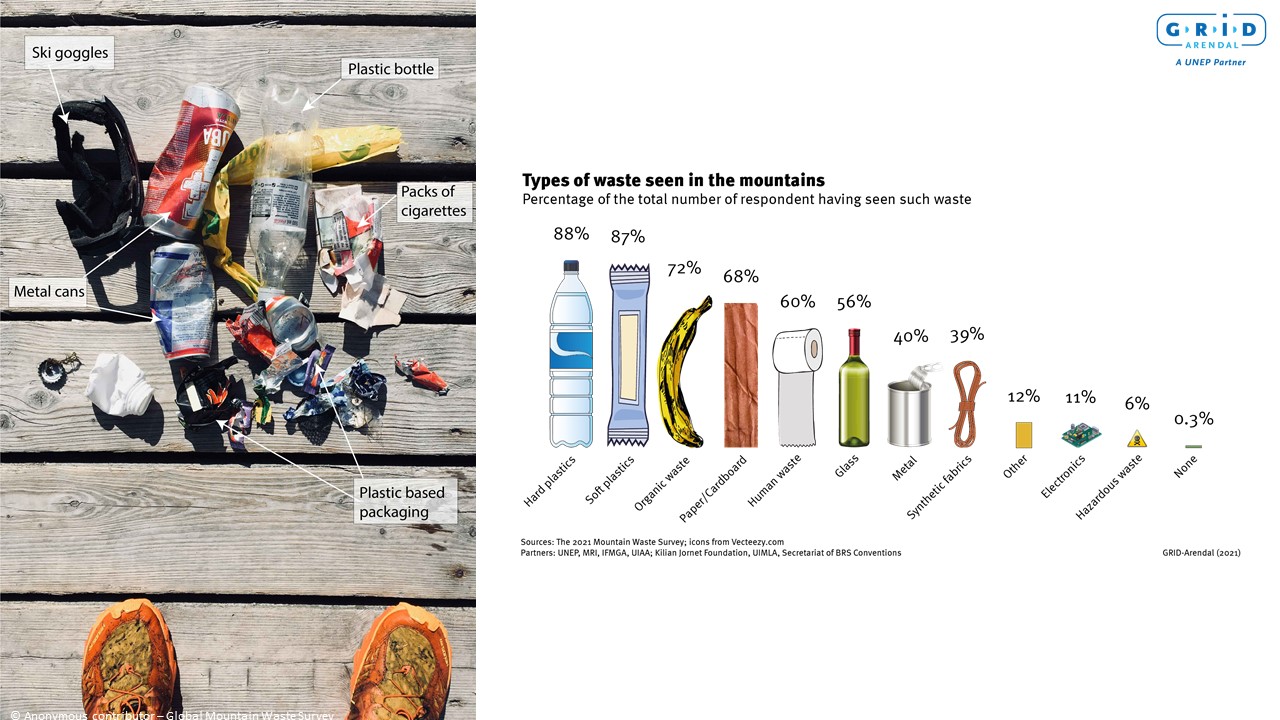

Overview of survey findings:

- What are the types of wastes have they seen?

- Hard plastics and soft plastics are the most widely seen types of waste found on the mountains, among them plastic bottles, cigarette packs, candy bar wrappers, metal cans, and equipment. But this global picture hides some peculiarities. Among the 400 mountain guides reached, they noticed a higher level of human waste than what the public had noticed. This may have to do something with their guiding practices and the amount of time they spend on mountains.

- In certain regions like Asia and Africa, electronic waste was higher than the global average.

- Where have they seen waste on mountains?

- It’s quite predictable where one can find waste: car parks at the bottom of mountains (where waste was seen the most). The responses also include trail heads beside the trails, resting areas, summits and refuges. Waste in crevasses, caves, lakes in forests were less seen, which maybe explained that responders spend most of the time on the trails.

- This is a positive news for the community as responding to the waste issue should be fairly predictable. We know where the sites will be as tourists tend to follow predictable trails up and down the mountains.

- What volumes of waste have they seen during a typical trip?

- Most European respondents said they saw little to none or could fill a top pocket.

- 46% said they could fill up the top pocket of a rucksack, where as the percentage decreases as the volume increases. 6% of respondents say they could fill several rucksacks, but this hides important regional differences. For example, in Asia and Africa, over 60% of the response said they could fill one or more rucksacks with waste found.

- What are the causes of littering?

- Respondents were asked to rate different statements, and found that negligence by mountain users themselves have the highest rating (averaging at 4.36/5.00). Poor waste management in resting areas was also a possible issue, where people want to manage their waste, but don’t have facilities to do so. Illegal dumping and unintentional loss of waste also scored high. These are already an indication of where we can work to solve the problem.

- On solutions to the waste issue

- How can we reduce or eliminate waste in mountains? 90% of 1,700 respondents thought that the adoption of the principles “Take in, take out” and “Leave no trace” should be adhered to in mountains. 79% thought that we need more education on the impacts of litter, while 66% found there was a need for more sustainable and reusable alternatives and these results are very consistent across all the regions. The results are very consistent across all the regions giving us strong mandate for education and working on sustainability issues and the said principles.

- Who should be responsible for mountain clean-up activities? 86% thought individuals should be responsible, followed by tourism and trekking associations at 56%. Third place goes to environmental NGOs while 49% mentioned the private sector. The third figure hides an important regional difference in Asia, where they felt that tourism, trekking associations as well as municipalities should play a very strong role. This may be due to the the fact that many of the opportunities for mountaineering in these regions are actually run through these associations so people feel that they have more responsibility for it.

- For more information, you can visit Plastic on the Peak. The survey was made possible through partnerships with UNEP, Basel Secretariat, UIAA, IFMGA, Killian Jornet Foundation, Mountain Research Initiative and the Union of International Mountain Leader Associations. A report may be published in January which dives more into the details.

Trends, Challenges and Policy Recommendations to Address Plastic Waste in the Mountains | Jost Dittkrist, Secretariat of the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Convention

- I would like to address three related questions: What drives plastic pollution in the mountains? Why is it particularly challenging to ensure the environmentally sound management of plastic in the mountains? How can we make progress in addressing plastic pollution in the mountains? I will draw on findings from research being undertaken for a forthcoming report Plastic Waste in Remote and Mountainous Areas which the BRS Secretariat is currently preparing in the context of a project financed by the governments of Norway and France.

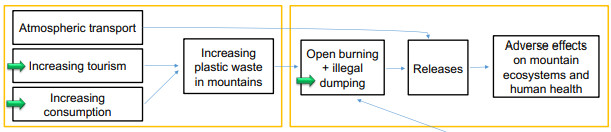

- What drives plastic pollution in the mountains?

- As in other areas, increasing economic growth translates into increasing consumption of plastic products and thus increasing generation of plastic waste. This is also true in the mountains but there is a significant plastic waste footprint of tourism including those related to construction.

- Tourism generates disproportionate amounts of single-use plastics and non-recyclable waste. They also tend to generate more plastic waste per capita than local populations. For example, research conducted in the Carpathians showed a strong relationship between the growing number of tourists and the growing number of municipal solid waste including plastic waste. In one community, tourism prompted a 38-fold increase in plastic waste generation per capita within just three years. Popular mountain tourist destinations such as the Himalayas summit or the Kilimanjaro have become hot spots, which is concerning because plastic waste often contains persistent organic pollutants (POPs) used as additives, from packaging to clothing and other mountain equipment.

- We have also heard of microplastics that travel long distances through the atmosphere and end up in significant quantities in mountainous areas, where studies have found “plastic rain” in the Alps, in the Pyrenees, the Rocky Mountains and in the Tibetan plateau.

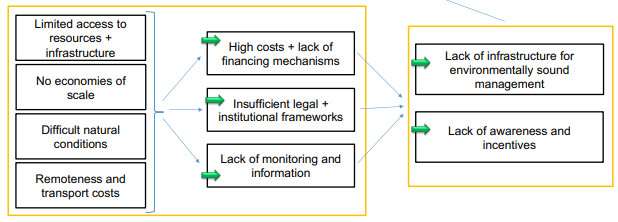

- Why is it particularly challenging to ensure the environmentally sound management of plastic waste in the mountains?

- Many mountainous areas face several compounding challenges in ensuring the environmentally sound management (ESM) of plastic waste. This includes remoteness, limited access to infrastructure, high transport costs, and lack of economies of scale. Mountainous areas tend to have lower levels of economic development and thus have limited access to human and financial resources.

- The ESM of plastic waste is therefore challenging for mountainous areas in less developed countries as it often results in lower collection rates. For example, similarly functioning transport and separation systems, sanitary landfills and recycling capacities are often not in place so this leads to increased rates of open dumping (including illegal dumping and open burning of plastic in mountainous areas) as observed in many places such as the Himalayas.

- All these issues can then lead to adverse effects on ecosystems and human health, as seen in the photo below.

-

- The different issues related to the situations in mountain areas (left-hand side) lead to high costs and a lack of financing mechanisms, insufficient legal and institutional frameworks and lack of information and monitoring. These lead to the situation we are faced with in such areas: a lack of infrastructure for plastic waste ESM and a lack of awareness and incentives to address the issue, leading back to practices that have adverse effects on mountain ecosystems and human health.

- How can we make progress in addressing plastic pollution in the mountains?

- In many of these variables, we can intervene. For example, tourism can be rendered more sustainable by working with tourists and tour operators to reduce their plastic waste footprint. We can also address increasing consumption using plastic-free alternatives or scaling up recycling. We can also extend producer responsibility systems fees and other financial mechanisms that can be implemented.

- Governments can act for example by banning the use of certain single-use plastics. Monitoring systems and data gathering can be established including in the context of national plastic waste inventories to help inform decision-making. Collection and separation systems can be implemented, as often small interventions can already make a big difference such as ensuring the availability of containers at tourist hotspots.

- Further awareness raising campaigns can lead to behavior change among tourists and locals alike and finally for the plastic waste that has already been generated We can engage in cleanup campaigns to help remediate the problem. There are large number of strategies available.

- We need to act at all levels.

- At the local level. Municipalities often carry the responsibility for running effective waste management schemes. Administrations of protected areas can implement schemes to prevent plastic products from being dumped. Mountain guides can educate tourists and lead by example. Everyone can make a difference by making sure that all plastic waste brought to the mountains is also taken back. However, resources for the ESM of plastic waste are often lacking at the local level.

- As such at a national level, to provide an appropriate national, legal and institutional framework (whether through banning certain types of plastic waste or providing fiscal incentives). As mountains tend to not respect national boundaries, cross-border cooperation at the regional level is critical. Finally, we also need to act globally and there are numerous initiatives at this level.

- Even if such partnerships and MEAs have a global scope, they will also help to protect our mountains. Plastic waste has adverse effects on a range of ecosystems including mountains and is an issue of global concern.

- With regards to the Basel Convention, the plastic waste amendments specify categories of plastic waste and mixtures of plastic waste generated by parties that are subject to the control procedures for transboundary movements. They are also subject to the provisions pertaining to waste minimization and environmentally sound management.

- Given the yet insufficient infrastructure in many mountain regions, an increased effort on preventing and minimizing the generation of plastic waste may be a promising strategy especially in the short to medium term as seen in the waste hierarchy outlined in the ESM framework of the Convention.

- To support governments, the COP also established the Plastic Waste Partnership, and the Secretariat is providing technical assistance to strengthen capacities of parties to address plastic waste. For example, we are currently preparing pilot projects to replicate success stories in North Macedonia and in Peru.

- Finally, various plastic additives such as POPs are regulated under the Stockholm convention so while further action is needed at all these levels, the good news is that efforts are already underway.

Mountain Guides as Ambassadors of Mountain Protection | Leif Inge Magnussen, International Federation of Mountain Guide Associations

- As part of the International Federation of Mountain Guide Associations (IFMGA), I’m representing 7,000 mountain guides from 25 countries. The Environmental and Sustainable Access Committee represents a broad view on the possibilities and the prospects of how to beat plastic waste and waste in general in mountains. We have also signed a commitment to implement principles in the Sports for Climate Action Framework.

- The basis of being a mountain guide trained by the IFMGA is that they all relate to a common code of conduct which clarifies that guides should respect the conservation of nature. When it comes to what this means in terms of waste, the guidelines also highlight that we are responsible for removing waste from the excursions, and in practice we also pick them up on our way and put it in the rucksack. This is a kind of indirect pedagogy where you’re leading by example

- As mentioned, 46% of plastic waste are seen on the summit. As an example, this collection of old ropework or slings in national parks are from pinnacles at the very top accumulated over a year. One uses these so that they can attach a rope and can go down abseiling to get off the mountain. However, every time a new climber comes, they add an additional sling. This is not a very frequented mountain so this was a collection accumulated over a year. The amount of waste carried by one guide somewhat signifies the problems that seem to repeat again and again. Mountain guides lead by example by ensuring that these links are picked up and replaced so that they do not accumulate.

- While the previous examples were examples of policies, mountain guides have also joined voluntarily this year the Stetind Declaration. It is a value-oriented way of committing oneself to nature and a declaration to be able to address your basic values [towards nature].

- On the policy level, the IFMGA and its 28 associate members associations are working systematically to promote greater environmental responsibility. We try to reduce our overall climate impact: we educate for climate action; we promote sustainable, responsible consumption; and we advocate climate action through communication. In all of this, we also take care of our waste and most often they also are carrying other people’s wastes down the mountain. This is the broad idea of how we work in practice but also in training.

The Role of Mountaineers as Mountain Stewards | Carolina Adler, International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation

- The UIAA, a federation of organizations from all over the world dealing with upland clubs, was founded in 1932. We are federating close to 90 members associations from 67 countries, with over 3 million people collectively – quite a considerable constituency. Mountain sustainability has been a core commitment of UIAA now for many years establishing the Mountain Protection Commission in 1969.

- Among the many activities being undertaken, one project we’re extremely proud of is the Mountain Protection Award. We’re very grateful for the support from Bally and the Bally Peak Outlook Foundation who saw the value in supporting this initiative for mountaineers of the world. The following video shows what the Mountain Protection Award is about and in particular, the five key areas that we are focusing to highlight as part of these awards.

- Among the five key themes (Conservation of Biodiversity, Sustainable Resource Consumption and Management, Mitigation of Effects of Climate Change, Sustainable Waste Management and Disposal, and Protection of the Environment through Culture and Education), there is a specific category on waste management. It’s particularly important to make sure that waste management is not just about picking up rubbish on behalf of others but should address the core issue in relation to waste as well as raising awareness of what impacts waste has to the mountain environment. It’s about instilling values about what a real mountain steward should be.

- Due to the COVID-19 situation, this year we’ve combined the proposals received from 2020 and 2021 into one category. We had a total of 24 projects from more than 30 countries and six continents. We saw quite a lot of challenges for many of the proponents in terms of being able to implement their projects in the mountains given the restrictions but nevertheless quite a number of projects have been able to fulfill a substantial amount of work that go beyond the everyday practices.

- We had the opportunity to award the best new initiative which is a waste management concept that is still being implemented in Chamonix mountain area of Montblanc (Projet Zéro Poubelle). This project was quite insightful as it’s about getting rid of rubbish bins so that people make conscious efforts think that whatever they bring they also need to bring back out.

- We also had a runner-up project called the MacGillycuddy Reeks European Innovation Partnership Project in Ireland. They have an innovative approach to also engaging with the local community and landowners to address problems related with access and responsible access to the mountains and what that means for those who engage in mountaineering and mountain activities. This was incredibly important to also emphasize the need to engage with local people.

- The winners of the award just announced last week are a particular project that we are very proud of. This is about an opportunity to engage with young people and to bring them to the mountains to support their training not just in terms of mountain skills other skills related to personal and professional development, but mostly to be able to engage with the mountain when dealing with mountaineering practices. The clip below takes us to a trip to the Gran Paradiso National Park where this project takes place.

- Fostering a community of mountain stewards for us means supporting a shift in mindsets and values towards mountain protection and that has to be embedded as part of what we do in our mountaineering practice, something that is innate to our nature. Working collectively, we’ve raised awareness about the importance and fragile nature of mountains for people and the ecosystems that depend on them, not just in the mountains but worldwide. At the same time we made sure that we recognize and reward those great examples of mountain protection so that we are in a position to also scale and transmit the key lessons learned so that we may replicate and also make sure that this inspires actions in other contexts in other parts of the world.

Success Stories from around the World in Addressing Plastic Waste in the Mountains | Lesya Nikolayeva, International Environmental Expert

- In the framework of the project Jost presented, we also prepared and collected a number of success stories from different continents, in mountain ranges and remote areas to demonstrate that there are already many ongoing activities and efforts by different actors at different levels. We also announced a call for submission of case studies by expert, whose experiences we have used. We also reused some case studies that are already in the Waste Management Outlook for Mountain Regions.

- Overall, we have more than 50 case studies and we grouped them into four categories:

- The first category puts together all initiatives that are related to policy. One example of which is from Nepal where they introduced a garbage declaration and clearance system for um expeditions. All hikers are requested to declare all items and food items before and after their expeditions. They then receive a clearance certification which serves as proof that the waste they generated in the upper camps have been brought down to the valley or the place where they can dispose them.

- The second category are infrastructure initiatives. In this example from Tian Shan, Kazakhstan, the initiative was implemented on the territory of national park and thanks to this, it became the first national park in the country that implements the environmentally sound management of the whole cycle of waste on its territory. Using the EPR system, they designed special trucks and installed waste containers in 30 different sites in the national park.

- The third category of initiatives are financial initiatives. This example from the Pamir Mountains of Kyrgyzstan where through financial incentives, organizers motivated local guides, hikers and volunteers to collect waste from the upper camps and bring it down. I personally also participated in this action, where I received a shirt as remuneration of joining the clean-up, that is part of a tradition that happens every year.

- The final category we identified are clean up and awareness raising activities. This example from different alpine countries had many volunteers and support from local authorities and alpine clubs. They organize big awareness racing initiatives and cleanup activities such as the clean-up tour which started in 2001 and remains active today.

- To conclude, I would like to share some policy insights to prevent, minimize and ensure the environmentally sound management of plastic waste in the mountain areas.

- First, local plans on plastic waste management are very important to develop and introduce into their policies and development plans. As the responsibility for the municipal solid waste management including plastic waste goes with the local authorities, it is not often that local municipalities have the financial and human resources to address these issues. As such, financial mechanisms and initiating incentive schemes could help to support municipalities.

- We also call for local solutions since these areas are isolated and have limited connections to bigger centers. We also suggest organizing targeted awareness-raising events and education initiatives, as it is also important to say that we should not excuse ourselves from our responsibility, behavior and habits in the mountains.

- Many initiatives in the protected areas have also demonstrated how plastic waste can be addressed. Because they have direct communication with the visitors, they could demonstrate these good examples and ideas among visitors to reduce and avoid plastic pollution in the mountains.

Acting Individually and Collectively to Address Plastic Pollution in the Mountains | Matthias Jurek, Secretariat of the Carpathian Convention

- To address the plastic pollution crisis in mountains both individually and collectively, there needs to be a kind of paradigm shift. It’s great to see a lot of actors and institutions quite active but there’s a lot more opportunities for a possible agreement to prevent plastic pollution.

- It is also an amazing opportunity to mainstream mountains into the discussions. Creating this kind of paradigm shift at the global level, we need to see what kind of actors are out there so that we can use their voices and networks to bring about and advocate for change. On International Mountain Day, Nirmal Purja, a famous Nepalese mountaineer joined our group of mountain advocates advocating for the plastic pollution crisis in mountains. He currently is in a documentary called 14 Peaks, where he managed to climb the highest peaks in the world in a six-month-and-six-day world record (beating previous record of seven years). Active in fighting against the pollution crisis in mountains, he’s also in the phase of organizing a big mountain clean-up. A lot are happening in terms of cleanups not just on the Alps but in other parts of the world including in the Hindu Kush Himalaya.

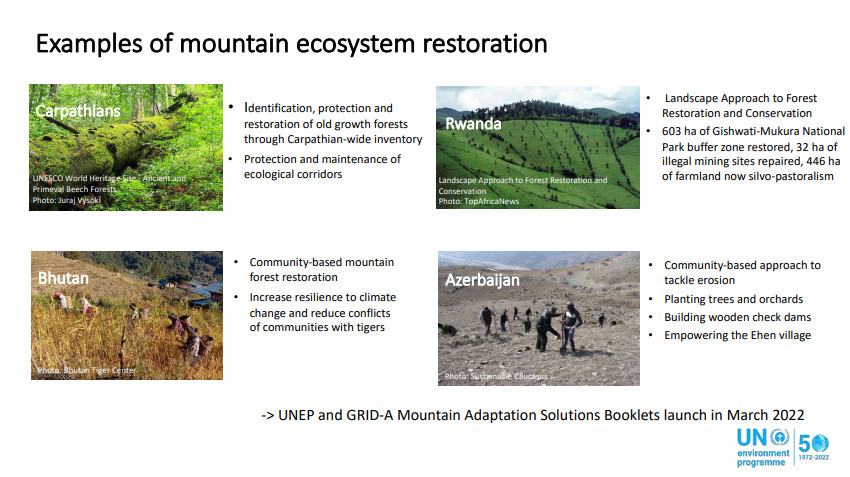

- There are many other opportunities to contribute to the triple planetary crisis of nature loss, climate change and pollution. One initiative is the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, which was launched this year on World Environment Day. This is not just an initiative driven by UNEP and FAO, but it’s something that we all own. We are part of a global movement launched by the UN General Assembly, where the aim to end degradation and restore ecosystems, including mountains. We also aim to achieve the global goals which are linked to the triple planetary crisis. Each of us has the opportunity to become active: whether through member states meeting an ecosystem restoration partner with concrete experience with restoration on the ground, or through individuals planting trees and supporting efforts.

- Here are some concrete case studies about mountain ecosystem restoration. There’s are a lot of examples on restoration that partners have been promoting and are also currently working on. These are available on the UN Decade website to see what opportunities are available to which you may wish to contribute.

- In celebration of International Mountain Day, the International Olympic Committee, UNEP and other sports federations are going to launch 10 Simple Steps to be a Mountain Hero. If you want to become a mountain hero, you can look at these different steps. Some of these may already be familiar, but I hope that others can serve as inspiration towards becoming active to protect the places you love. For example, how you travel to the destinations, you can ask: what are the kinds of means of transport that you’re using? What you do with the waste we produce? What kind of products are you consuming? You can also be yourself a role model and inspire other people in your different networks so we can all be part of this system change. You can be a mountain hero yourself.

- There’s a lot you can contribute, so please check out our website for more information and stories. I also hope you join the restoration in support of the UN Decade.

Q&A and Closing

Q: Who pays or who should pay for these actions? It all comes down to money, at the end of the day.

- Jost Dittkrist, Secretariat of the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Convention

- Very good question. Individually, there’s a lot we can do but we also need the infrastructure which has certain cost implications. However, there are several things that can be done and I would like to go back the different levels mentioned at which we need to take action.

- For example, at the local and national, one option is to implement extended producer responsibility schemes. Major companies that produce plastic products or that sell plastic products could be brought together so that a share of every plastic product they sell could be used for a fund which in turn can be used to finance the setting up of a collection system in certain mountainous municipalities.

- Another option for example is to implement tax systems. There are already several countries around the world that have introduced a tax levy on both imported and produced plastic products. These can then be channeled into a fund that is explicitly meant to cover interventions towards the environmentally sound management of plastic waste.

- More generally of there are other tools available, a bit more small-scale, such as asking people to bring to bring back waste, where for every kilogram or so of waste collected by the tourist or mountaineer, they would receive a little present like a reusable cup. It’s not that about always about financing the intervention but also making the intervention cheap and engaging in reducing their footprint.

- Patrick Umuhoza, Rwanda Environment Management Authority

- We conduct environmental reviews for companies, who have a grace period of one year to pay 90 Rwandan francs for each kilogram of single-use plastics used for packaging in their juice and water, for example. This money is collected by private sector federation in a certain fund used for the waste collection and recycling. There is a need of financial support, but we can start from ourselves and look for “homegrown” solutions.

- Matthias Jurek, Secretariat of the Carpathian Convention

- In the last years, the plastic pollution crisis was high on the agenda when it comes to the ocean. This is a great opportunity to shed some light on the mountains and to see if governments can come in and support this by providing financial opportunities to fight the crisis. Obviously, governments have their own agendas in terms of mountains. We do work very closely with donors on the development cooperation side, where much of the focus has been on climate change adaptation and biodiversity but perhaps with pollution as a topic coming up, we hope there is great opportunity to support concrete action.

- Carolina Adler, International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation

- It is an important question, and our experience at the UIAA shows that contributions and support from foundations have been instrumental to support communities and activities. But I would also like to highlight the importance of non-income contribution that goes into all these efforts. It would not be possible to realize these projects without the volunteers and the community.

Q: What are the status and the next steps of the global treaty on plastic pollution?

- Patrick Umuhoza, Rwanda Environment Management Authority | During COVID-19, we reviewed the final version and sent the comments together with the representative from Peru. We are in touch and we are still looking for how we can start with the signatures.

- Damaris Carnal, Switzerland’s Focal Point for UNEP | We have a resolution from Rwanda and Peru. Right now, it has around 45 co-sponsors and the idea is to be able to launch the process and establish a body that would be mandated to negotiate such a treaty by end of February or the beginning of March at UNEA 5.2.

Concluding Remarks | Damaris Carnal, Switzerland’s Focal Point for UNEP

- It’s now clearer than before that plastic waste in mountains is an issue of global concern. We cannot tackle it alone, and as Patrick mentioned, we need to join hands.

- It was also clear that we need to work at all levels, from local to global. We heard a number of fantastic initiatives at the local and regional level, but as highlighted there’s also a need to engage at the global level under the auspices not only of existing initiatives in the context of the Basel and Stockholm Conventions, but also in the run-up to UNEA 5.2, trying to foster global action to tackle plastic pollution.

- It was also clear that data and knowledge need to be enhanced. A few reports and upcoming research were mentioned so we will very much look forward to reading them and to factor these in our reflections.

- A final point was the importance of education and raising awareness on this issue of plastic pollution in the mountains. This kind of event and knowing about all these initiatives also contribute to this. I’m hoping this is not the end but the start of further engagement and conversation on the matter.

Documents

Resources

- Plastic Waste in Remote and Mountainous Areas Project (financed by the Governments of Norway and France)

- Plastic is the most common type of waste encountered at altitude, finds global survey on litter on the world’s mountains (2021 Global Mountain Waste Survey) | GRID-Arendal | 5 June 2021

- Plastic on the Peak

- Mountains of Plastic | BRS | 10 December 2021

- With litter piling up, mountain tourism reaches a crossroad | UNEP | 10 December 2021

- From Pollution to Solution: a global assessment of marine litter and plastic pollution | UNEP | 21 October 2021

- Recommendations for the tourism sector to continue taking action on plastic pollution during COVID-19 recovery | UNEP, UNWTO, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and the Global Tourism Plastics Initiative | 2020

- From sea to summit: IOC launches sports group to protect mountains be a Mountain Hero | IOC | 11 December 2019

- Plastic in the Mountains | International Mountain Day 2018 | Geneva Environment Network | Read the report and watch the event

- UN urges renewed efforts to protect mountains – as well as oceans – from plastic waste | BRS | 11 December 2018

- Mountains of Plastic | BRS | 10 December 2018

- Plastics and the Environment | Geneva Environment Network | Updated regularly

Links

- International Mountain Day | United Nations

- Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions

- GRID-Arendal

- International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (UIAA)

- International Federation of Mountain Guides Associations (IFMGA)

- Global Tourism Plastics Initiative | UNEP & World Tourism Organization (UNWTO)

- Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-Based Activities | UNEP