Event Conference

Climate Tipping Points, Irreversibility and their Consequences for Society, Environment and Economies | Switzerland’s Proposal for an IPCC Special Report

25 May 2022

10:00–11:30

Venue: International Environment House II & Online | Webex

Organization: Switzerland, Geneva Environment Network

Organized with Switzerland, this briefing presented the initiative asking the IPCC to elaborate a Special Report on “Climate Tipping Points and their Implications for Habitability and Resources”.

About this Session

Over the past decades, our scientific understanding of climate change has significantly grown. The IPCC reports has played a key in synthetizing the best available science on the causes of climate change, its impacts, and possible pathways to adapt to and mitigate them. Meanwhile, scientific information on large-scale singular events, tipping points and irreversibilities remains scattered. Tipping points in the climate system refer to thresholds that can occur as a consequence of human induced climate change, and that lead to changes are abrupt, high-impact, large-scale and often irreversible.

This lack of a comprehensive assessment on the issue hinders an overview of the state of knowledge and limits decision-making in accordance with Article 2 of the UNFCCC and Art. 2.1(b) of the Paris Agreement. In particular, emerging measures and the acceleration of climate change in recent years have increased the need for a comprehensive and focused assessment of tipping points in the climate system.

To respond to this need, the government of Switzerland considers it timely and pertinent to ask the IPCC to elaborate a Special Report on “Climate Tipping Points and their Implications for Habitability and Resources”, which will be prepared in the framework of the IPCC’s 7th Assessment Cycle, scheduled to start in 2023. All three IPCC Working Groups are expected to contribute to this Special Report, making it a comprehensive assessment of the topic. The timing of the approval of the report should take place around 2026 in order to serve as the basis for the second UNFCCC Global Stocktake from 2026 to 2028, and well before the second commitment period under the Paris Agreement in 2030.

The goal of the event is to lay out as to how the crossing of tipping points in the climate systems may impact society, environment and economies alike, across the globe.

Organized with Switzerland within the framework of the Geneva Environment Network, this event presented the initiative to governments participating in the IPCC and Parties to the UNFCCC and other interested stakeholders.

Speakers

Thomas STOCKER

Professor of Climate and Environmental Physics, Physics Institute, University of Bern & President of the Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research

Sebastian KÖNIG

Chief Scientist, International Affairs Division, Swiss Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) & Focal Point for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Switzerland

Maria NEIRA

Director, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Health, World Health Organization

Sabine PABST

Environmental and Climate Destruction & Asia Coordinator, FIAN International Secretariat

Jürg LUTERBACHER

Director, Science and Innovation Department & Chief Scientist, World Meteorological Organization

Summary

See the presentation made during the event.

Welcome and Opening

Sebastian KÖNIG | Chief Scientist in the International Affairs Division, Swiss Federal Office for the Environment, IPCC Focal Point for Switzerland

418.9 ppm. That is the level of CO2 today. That number is already at levels last seen around four million years ago, in the Pliocene epoch, when temperatures were up to 3°C higher than than today.

7 Meters. That’s the equivalent of global sea level rise that the Greenland Ice Sheet holds. We now measure that Greenland is losing ice at fastest rate in 350 years.

In my own research 10 years ago, we wanted to understand how sensitive large systems like the Greenland Ice Sheet are and what the future may hold. Back then, the Greenland Ice Sheet was almost lost entirely. Once the ice is lost, it requires levels of CO2 half of the current levels and orbital configurations favorable for ice to grow, which could take multiple thousands of years.

Politicians, economists and even some natural scientists have tended to assume that tipping points2 in the Earth system — such as the loss of Greenland Ice sheet or the Amazon rainforest — are of low probability and little understood. Yet evidence is mounting that these events could be more likely than was thought. By crossing a tipping point, the Earth is entering a new stage of a climate regime, which is irreversible, at least for a very long time.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) introduced the idea of tipping points two decades ago. At that time, these ‘large-scale discontinuities’ in the climate system were considered likely only if global warming exceeded 5 °C above pre-industrial levels. However, new information suggests that tipping points could be exceeded even between 1 and 2 °C of warming.

Representatives attending this meeting are now wondering why they should be concerned about the fate of the Greenland Ice Sheet. The answer is twofold.

- First, the climate-biosphere system is interconnected: Crossing a particular tipping point will lead to feedbacks, cascading effects and to changes elsewhere on the globe, taking us to a different climate regime. Prof. Stocker will be diving into the details on that.

- Second, it will have significant social and economic consequences. On these consequences, we will hear more from our distinguished panel: on how societies and economies will be and are already impacted.

Given the high interconnected nature of the tipping points and given the far reaching consequences for mankind, we need a comprehensive understanding of the tipping points and their implications. It is hence, highly policy relevant information.

The IPCC is the right authority and delivers the quality for such a report. Therefore, Switzerland sees it as pertinent to call for a Special Report by the IPCC in the new cycle that will start by 2023. We ask governments and other stakeholders to sign up to and join our proposal. A first step would be to have COP27 to mandate the IPCC to undertake such an assessment.

Climate Tipping Points and their Irreversibility | Presentation of the Proposal for IPCC Special Report

Thomas STOCKER | Professor of Climate and Environmental Physics, Physics Institute, University of Bern & President of the Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research

The IPCC has laid a great foundation to look into climate tipping points in more detail. Temperatures in the last 2000 years have increased to a level that is unprecedented in that time, where the rate of change is also unprecedented.

- It’s useful to look back 60 million years that has been done now by IPCC in the Working Group I contribution: we find carbon dioxide concentrations as estimated 60 million years ago to 1 million years ago and the global surface temperature changed during that time.

- There is a very tight correlation between the major greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, and the global mean temperature as greenhouse gases and their variations modify the earth’s energy balance.

- We have also become even more precise about these two parameters in the climate system over the last 800,000 years. If you put that together with the projections first historical development over the last hundred and 150 years and then the projections that were presented in the Fifth Assessment Report.

- The context of the changes that lie ahead of us in only the next 200-250 years, with respect to the last 60 million years. The world has the potential to be rather different from now, as seen in the evolution of the temperature on a map from the last 60 million years to today.

Emission scenarios at 2100 and 2300 timescales.

- With regards to emission scenarios, at the time horizon of 2100 for the mitigation scenario, we’re looking at the world in which people are able in most regions to adapt to the impacts of climate change. In a world, however, where high emission scenario (SSP-8.5) would be realized, this is no longer guaranteed and many areas on this planet will go beyond the limit of habitability. This is a real danger that needs to be assessed in a more profound way.

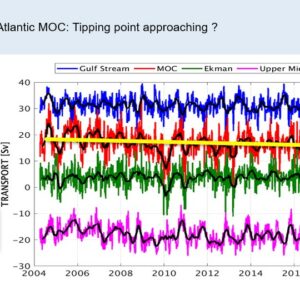

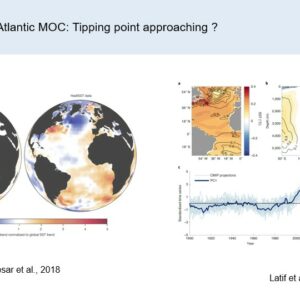

Tipping points have happened in the past. During the last ice age, we had about 26 events where scientists believed that tipping was the element that triggered these abrupt temperature changes, as seen in the Greenland ice cores and the consequent changes around the globe, registered in the red curve as temperature variations that are correlated with the abrupt changes in Antarctica. [See graph here.] Tipping points are not a figment of a mathematical model but in fact our planet has dynamics that are seen in both global scale and regional scale tipping points.

Science has progressed in the last 20 years to identify step by step possible non-linear processes in the climate system: the interaction between the atmosphere, the ocean and the land surface, including vegetation. We have identified a number of tipping elements, some are already present in the literature as robust knowledge, others are more speculative, but that is the state of the science at the moment.

Examples of tipping points. From the Gulf Stream System, polar ice sheets, to El Niño phenomena, here are a few examples of tipping points mentioned during the presentation. Click on the image to see more details.

The [varying studies on tipping points] indicate that an assessment by IPCC would extreme would be extremely useful to inform public and policy makers about the state of knowledge.

Perception of tipping points. There is a lot of confusion in the public, with several examples in the media that argue that tipping points are just around the corner, and we need to be shocked about that information. Others would argue that tipping points are rather an element that occurs in the modelling realm, and therefore observations are not really confirming their existence. We can safely conclude that some clarifications and an assessment with consensus is needed.

Global research programs have started seriously to focus on tipping points:

- Future Earth has issued an overview of tipping point research in terms of paleo research.

- World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) has launched a series of Lighthouse Activities which also focuses, among other things, on tipping points, or high impact, low likelihood events.

- This is also reflected in an ongoing discussion series, “Tipping elements, irreversibility, and abrupt change in the Earth system” that has been launched last year and is still ongoing

IPCC’s work on tipping points.

- AR3. Surprises in the climate system, unexpected events, and abrupt climate change were featured in various parts of the report but in an uncoordinated way because it was a new topic at that time.

- AR4. The focus was indeed on the Atlantic Meridianal Overturning Circulation (northward extension of the Gulfstream). Polarized sheets have been around in the literature for years, this was assessed in AR4 as well.

- AR5. We address tipping points now more specifically. We also looked at the irreversible changes in all climate system impacts but we had to report the fact that the studies were not really numerous at that time to warrant a deeper consensus finding process during the 5th assessment cycle.

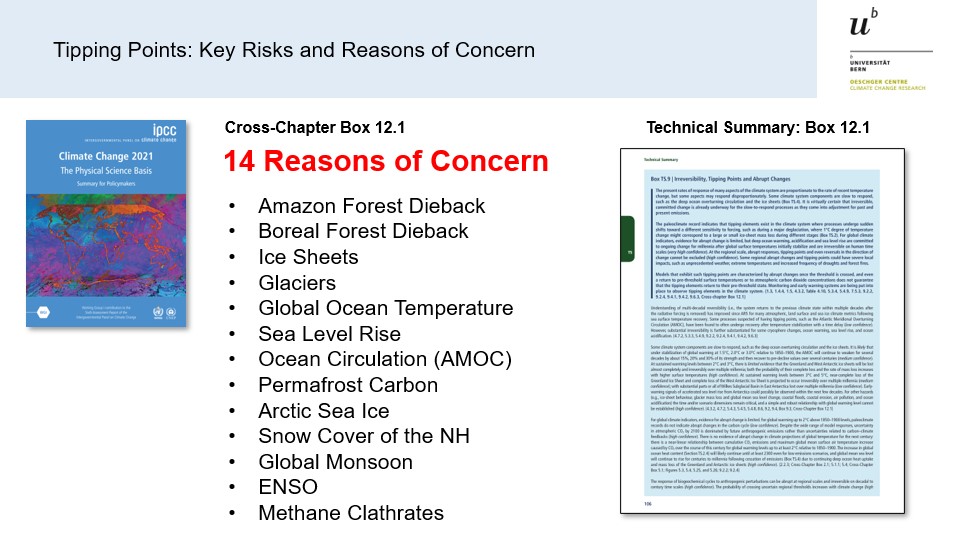

- AR6. Closing soon, we have special reports on the ocean and cryosphere, where tipping points are already featured prominently. In the technical summary, as well as the comprehensive report of WGI, they identify 14 Reasons of Concern. They also decided, at the technical summary level, to feature a box (one and a half pages long) on tipping points that would inform policymakers on the state of knowledge.

14 Reasons of Concern IPCC AR6 WGI report on Tipping Points.

Risk of tipping points. The important communication on the risk of tipping points and other climate change related risks is usually expressed in these burning amber diagrams. If you identify the 2° Celsius target to which we should stay considerably below according to the Paris Agreement, large scale singular events (or tipping points) are already in the reddish area at that temperature, where the risk is increasing rapidly when there is an overshoot beyond the threshold.

Tipping points, however, occur at all scales: it is not just about global tipping points but tipping points associated with weather systems that concern hydrological cycles and ultimately the resources of people. Of the fourteen reasons of concern, those in red show tipping points that are already present in the literature. You see this is a growing list and so there is material to be assessed in the seventh assessment cycle.

Proposing a special report. Why a special report? A special report on a specific topic allows you to involve a good number of authors around the world who are working on that topic. That means that you can reflect the knowledge base to a much greater and deeper extent than just addressing that topic in a special box somewhere in an assessment report.

Its function is nicely illustrated in the special report on extreme events commissioned in the 5th Assessment Cycle in 2012. From my own experience, this has accelerated research on that very topic, and is the reason AR6 is able to say much more relevant things about extreme events and changes in statistics and intensity around the world. This is of crucial importance. Therefore, a special report is really an instrument not only to provide a consensus but also to boost the knowledge in the long term.

Conclusion. I present an extract of a proposed table of contents. It is key to address impacts (WGII) and economies (WGIII). These are topics that are still in their infancy but would be extremely useful to involve these communities when it comes to tipping points because this is the information that people need to make decisions at their community levels.

- Tipping elements are reasons of concern now. They are global and regional impacts that pose key risks for humans and ecosystems alike.

- A comprehensive scientific assessment of tipping points and their regional impact is missing. We don’t have information. We don’t have a comprehensive consensus-finding project, and tipping points are not yet part of IPCC scenarios.

- A special report would certainly put that on the table and make the scientific communities think about a scenarios.

I support the call for a report. It is an opportunity that should not be missed in the seventh assessment cycle. It is important to involve especially Working Groups II and III, on impact and socio-economic processes, because only a comprehensive assessment of a special report that involves all three working groups would provide the actionable knowledge for decision makers to address that important topic.

Panel Discussion | Tipping Points Consequences for Society, Environment and Economies

Health Impacts, including vector-borne diseases and epidemics | Maria NEIRA, Director, Department of Public Health and Environment at the WHO

Climate change is the biggest public health threat that is facing humanity now. WHO will be supporting any initiative that will allow us to accelerate and put at a real scale the actions that are needed to face this major public health issue.

I would add the issue of human health to the 14 Reasons of Concern mentioned. We are trying to link the health argument at the center of the linkages between climate change and human health, while giving a positive narrative to motivate, further, motivate, engage citizens in having an active role and placing political pressure.

How is climate change impacting our health?

- One, with the increase in frequency of these natural disasters, we are very much concerned about how this impacts the health of people, causing them long-term diseases and immediate death.

- Second, climate change has increased climate-sensitive diseases. This means there will be more food borne diseases, that can affect food production and eventually the health of humans. Vector borne diseases, such as those from mosquitoes, will find the perfect conditions to grow, to reproduce, increasing the likeliness of diseases like dengue or malaria. Zoonotic diseases have arisen because we are not respecting ecosystem barriers between humans, animals and the environment. [Learn more about One Health.]

- As seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, we will see more emerging infectious diseases since we are destroying ecosystem, biodiversity, and this natural barrier, due to deforestation or agricultural practices.

- Third, climate change is touching the pillars that sustain our health: access to safe water, access to food, access to clean air, and access to shelter. If you destroy those four basic pillars that protect human life and human health, then we will be suffering. Climate change is also having an incredible impact on mental health, and we will soon produce a second report on all of that.

There are enormous benefits in tackling these issues head on.

- First, having clean air is just as fundamental to our health, with seven million premature deaths caused by exposure to air pollution. For us, this is a great opportunity: tackling the causes of climate change will generate enormous health benefits particularly coming from this reduction in the pollution of the air we breathe. How is this air pollution produced? It overlaps with at least 75% of the causes of climate change, as a big proportion comes from the combustion of fossil fuels.

- The second huge health benefit will come from a change in diets and sustainable food production and consumption.

- Third will come from healthy urban planning. It is important to plan our cities in a different way that will protect us, have more energy efficiency, renewables, among others – all of which are needed to implement the Paris Treaty. At the end of the day, the Paris Treaty is a public health treaty.

Therefore, we are involved in climate change negotiations and debates, presenting the argument for more action because we are convinced that this can be a very strong engine to motivate people to act. People understand the connection between air pollution and health. Maybe they don’t see the connection immediately but when you explain this overlap between diseases and the climate, they may understand. This can generate a movement that we should take advantage of.

At a press conference on WHO air quality guidelines, a journalist asked, “What would be the situation of human health if we go beyond the tipping point? I reply, “I don’t want even to imagine that, and I don’t think you want to have it. The moment you present that people start to accept, so it is unacceptable for us.

I ask that you place the health argument as a main cause of concern because we are very quickly reaching the tipping point for public health.

Climate change related displacements | Alexandra BILAK, Director, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre

We recently released the 2022 Global Report on Internal Displacement. This report showed that internal displacement is very much a global phenomenon, and we have now reached global record levels of displacement.

The majority of people living in internal displacement today have been displaced originally as a result of conflict and violence. However, based on annual figures, we see that every year the most common drivers of movements and the dynamism of internal displacement is mostly weather- and disaster-related:

- Last year alone, the sudden onset of mostly weather and climate related disasters triggered 23.7 million displacements.

- Majority of these displacements that occurred in East Asia and the Pacific took the form of storms and floods. Every year, we report high numbers of displacements in three countries (China, India, and the Philippines).

- Most of these displacements are in the form of evacuations, and one could think that this means that this displacement is short term. However, looking more closely, as houses are destroyed or damaged to such an extent that they can no longer return, it’s going to take them more time to return, as they may not have access to insurance or have lower levels of income. As displacement becomes prolonged over time, they can even become permanent.

- The numbers were slightly lower last year than they had been in previous years. However, the phenomenon still occurred in around 70% of the world’s countries and territories.

- In 2021, drought conditions and extreme temperatures that caused wildfires across the Middle East and North Africa but also in areas of North America and Europe shows that this is not just an issue that is affecting lower income countries but also high-income countries.

It’s important to mention that it’s hard to establish a direct sort of causal relationship between climate change and displacement. In fact, today, people are fleeing multiple threats that are caused by a combination of political, environmental, social and economic factors. We see conflicts combined with weather and climate disasters that are causing increasingly protracted forms of displacement.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic and now the war in Ukraine are exacerbating people’s vulnerabilities and they’re creating situations that are becoming more and more difficult to resolve.

- We’ve seen this across for example areas of the Pacific in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic that was still being hit by hurricanes and you know flooding and where governments were literally unable to to evacuate people or to provide shelter because they also needed to respect social distancing measures.

- This led to complex forms of vulnerability where people were not being provided with immediate humanitarian assistance. The effects are being felt most strongly in low- and middle-income countries or even within poorer and disadvantaged communities within such countries.

- Today, parts of Africa are going to be entering their fifth consecutive failed rainy season. They are hard hit by a global rise in food prices which has led to acute food insecurity and put millions of people at risk of famine. Alongside conflict, this is leading to people becoming displaced repeatedly and facing now the risk of a permanent loss of homes and livelihoods.

- We can no longer dispute the relationship that exists between conflict, disasters, food and security and displacement. If you look at the four countries in the world with the highest numbers of severely food insecure people which are DRC, Yemen, Afghanistan and Syria. They are also the countries they are also conflict affected countries and they’re among the the five with the highest numbers of IDPs.

- With regards to the mental health dimensions, what we’ve shown is how children are disproportionately affected within these crises. Alongside conflict, displacement and malnutrition or food insecurity, there’s a correlation with school closures and education cycles interrupted, having knock-on effects for their future, socio-economically but also with regards to their mental health. As such, we also need to consider the costs that this is likely to have for future generations.

We’ve been trying to quantify, collect data and generate evidence on how the slow onset effects of climate change are driving displacement. There’s very little available evidence out there precisely because it is a multi-causal phenomenon. However, there are two areas where there is growing evidence.

- Global sea level rise is causing damage to coastal infrastructure and loss of territory. This means that more people are exposed and vulnerable to sudden onset disasters and to a risk of displacement. This is particularly relevant in small island developing states (SIDS), with their low elevation, limited territory, and dependence on natural resources. It means that they’re already having to think about the permanent relocation of these communities. This isn’t specific to the Pacific region. We’re also seeing it in other countries from Indonesia to Senegal.

- Desertification is another example of how slow onset effects of climate change are contributing to people being forced out of their homes. Low crop productivity, in certain areas of the African continent, for example, is causing their livestock to be no longer usable for pasture, forcing them to either move into other forms of income generation and livelihood, and causing some people to move into urban areas where oftentimes they receive no assistance. These people then drop off the the radar, making it impossible to understand what their needs look like and the kind of support needed.

With all sorts of examples across the world of how tipping points are going to increase global future global displacement, I recall the question that Maria receives from journalists who are trying to kind of anticipate or project into the future. We often get the same question: what is this going to mean for displacement? Are we talking about hundreds of millions of people fleeing? Are they coming to Europe? To the US? I think our answer is very similar: we’d rather not have to think about it.

Agricultural shifts and farmland abandonment, stress on food and jobs | Sabine BAPST, Environmental and Climate Destruction & Asia Coordinator, FIAN International Secretariat

FIAN International is an international human rights organization focused on the human right to adequate food and nutrition, and I would like to focus on the relation between the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment and the right to food and nutrition as they are closely connected.

We have to consider in this context that one of the main drivers is the prevalent industrial food system. This covers a whole range of of issues, such as the input supply and production of crops, fish, livestock and other agricultural commodities, transportation, processing, retailing, wholesaling, the preparation of food, the consumption and the food disposal. Here are some examples:

- According to studies, at least one third of all greenhouse gas emissions are caused by the industrial food system (other calculations show that this amount is even more). All the processes linked to the food system are linked to huge fossil energy consumption and the related negative impacts on the climate.

- The destruction of biodiversity can be seen through deforestation and peatland conversion and the application of fertilizers and pesticides, and their impacts on soils, water bodies and air.

- The industrial food system is also responsible for an increased vulnerability of large parts of the population through a combination of factors, for example, through the destruction and pollution of water sources and water bodies. The availability of clean water is critical for irrigation but also as a source of fish and other forms of aquatic life.

- The destruction of fertile farmland, forests, passage, pastures is a problem for biodiversity. Soil degradation mainly caused by deforestation and industrial agriculture is also a massive problem. One third of all fertile soils considered as degraded, the future scenario sees that 90% of all soils will be degraded in 2050 (FAO and ITPS, 2015; IPBES, 2018).

It is marginalized and disadvantaged groups who suffer most from these impacts, especially if there are no coping mechanisms: small scale food producers including small and marginal peasant farmers, indigenous people, agriculture workers, herders and other small livestock keepers, rural artisans, small entrepreneurs. For example, they are usually not able to use irrigation or install pump sets. They usually do not have alternative income possibilities due to lack of education or assets. They often do not have the possibility to migrate because they lack the resources for it.

Because the industrial food system relies on the global market and international trade, it causes increased vulnerability. For example, for the agricultural workers who already work under precarious and often informal conditions. The COVID pandemic and as well the ongoing war on Ukraine are some recent examples.

Therefore, the promotion of agroecological practices and the transformation of the prevailing food systems towards sustainable and resilient systems based on agro-ecology is an urgent need. This is part of the international obligations under the human right to adequate food and has been highlighted among others by the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, Michael Fakhri [Read more on SR Food’s statement at HRC49].

Finally, I would like to stress that communities’ rights to land, food and the environment are not only threatened by our prevailing systems. but their rights are also essential to address the current crisis, including the dangerous consequences related to the tipping points. Strengthening community and indigenous land rights and promoting agro-ecological food production are among the missing links in climate change mitigation. They are important bottom-up solutions and so far receive very little attention in official climate summits and reports. They are key to develop sustainable and just solutions.

Financial impacts, including insurance premiums above affordability threshold | Eric USHER, Head, United Nations Environment Programme’s Finance Initiative

The global financial community can be seen as a new user group of the science on tipping points. UNEP-FI establishes global frameworks for responsible conduct within the finance sector, some of which are relevant to science.

Climate disclosures. When talking about climate, climate disclosure comes to mind. Publicly listed companies, listed on stock exchanges, are required legally to disclose all financially material risks to their business: those who buy their stocks are aware of all risks that the company operates within.

- As part of the Paris COP21, the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) was launched. This put together a set of recommendations for how corporations should start to disclose climate risks. This voluntary framework presents corporations, banks and investors with an understanding of challenges, as climate risk has never been predicted before.

- As such, the science for the first time really starts to become key to the actions of most corporations for them to start being predictive and understand scenario models.

- Banks and investors need to start stress-testing their investment portfolios to understand what happens in a three to four degrees world, as investments are likely to fail because of the physical climate risks or the risks associated with policies and technology needed to address the climate transition. This has started the work to figure out how to set norms and disclose these risks.

Despite being initially voluntary, most big corporations in the last five years have started to disclose climate risks. The quality of disclosures varies, but regulators have now started to pick up on this.

- As we have a breadth of disclosures, we now need to improve the depth in terms of their comparability, gathering a proper idea of the risks different sectors are playing. This relationship between voluntary action within the private sector and regulatory action has been working quite well together. The finance sector for the first time learned about the IPCC and appreciated it for the tools it provides.

- The derivations from the IPCC in terms of international energy are also key to the sector. Indeed, the International Energy Agency (IEA) provides very important modelling and projections on energy markets. When a climate scenario is provided, the financial and economic systems are better able to understand and take better decisions.

Climate action. Climate disclosure and risk management alone are not enough. Altering portfolios to do well in a five-degree world does not solve the world’s problems. We need to take climate action. Paragraph 2.1c of the Paris Agreement, claims that the Parties must work to “making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development” and to align with the objectives of the Agreement.

- There has been a lot of work around climate disclosure and other work to align with the objectives of the Paris Agreement. At COP26, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) was funded and different parts of the financial community are starting to set targets and choose scenarios they want to work towards. They are then starting to adjust their portfolios and where they allocate financing to help deliver.

- It is mostly focused on a net-zero 2050 target but the challenging part regards choosing the model to use between IPCC, and IEA, and setting targets for 2025 and 2030. Predicting something for three decades out is easier than starting to reduce emissions.

- One of the leading groups which we convene within the GFANZ is the investors and asset owners. These pension funds and insurance companies have issued a target setting protocol for 2025 reductions.

- It uses the One Earth Model, where to get to zero by 2050, they need to reduce by 2025 in the range of 25 to 30% of emissions within their portfolio. As this is due in three years’ time, they are currently developing a strategy.

- This group has also established a scientific advisory body – being the first time that a financial group recognized the need for scientific advisors for their work. With continued policy uncertainty on climate action, the financial community is deciding to look at the science to increase the predictability of how markets, and regulations are going to change and how to adapt these.

The Inevitable Policy Response research body claims that if financial actors are in a market where there has not been a sufficient policy response to climate action, they must not take it as a reason to sit back, but rather pay more attention to it. The policy response will inevitably come, and the later it comes, the more brutal it is going to be.

Therefore, those who work in markets where carbon is not priced, better pay very close attention to it because when it comes, it will not be incremental.

Conclusion. The finance sector is a new user of climate science. Financiers have always kept an eye on market tipping points. As according to the Minsky Moment concept, market sentiment can change suddenly, and market values can collapse overnight. That is happening right now in the markets of many sectors, including the tech sector. Therefore, they see the value and need of understanding climate science.

It is therefore important for the IPCC to fill the current information gap on tipping points. This will be a key help for the financial community to understand which model to use as so far, the IPCC has set the standard to ensure they are part of the solution.

WMO’s view on the timely proposal | Jürg LUTERBACHER, Director, Science and Innovation Department & Chief Scientist, WMO

The WMO published its 2021 State of Global Climate Report, which in the words of the UN Secretary-General represents a “dismal litany of humanity’s failure to tackle climate disruption”.

- Gas concentrations, sea-level rise, ocean and sea acidification all set new records in the last year.

- A series of alarming and exceptional events were recorded, including the first-ever recorded rainfall at the summit of the Greenland ice sheet at over 3000 meters. The Report also made it clear that many glaciers across the world are close to a tipping point. It is not just glaciers; ice sheets in Greenland and West Antarctica are being closely monitored for signs of abrupt changes.

- Deforestation, climate change and changes in land use are destabilizing the Amazon rainforest. Since 1970, almost 20% of the Amazon rainforest has been lost.

- The climate indicators also suggest that we are edging closer to tipping points in the oceans, the cryosphere, as well as the atmosphere.

- The UN Convention to Combat Desertification launched the second edition of its flagship publication, Global Land Outlook, which made clear that four out of the nine planetary boundaries have already been exceeded: climate change, biodiversity loss, land-use change, as well as geochemical cycles. Other boundaries are also close to threshold levels.

These boundaries or tipping points define a safe operating space for humanity. We are now risking further widespread, abrupt, or irreversible environmental changes as the habitability of our planet decreases and we move further away from the safe operating space. The research on landscape related to tipping points, irreversibility and abrupt change is thriving as well as on potential implications and impacts. These come as direct responses to an awareness that sudden and unexpected shifts in earth’s climate are increasingly likely with a changing climate.

Since September 2021, the World Climate Research Programme has been running a successful discussion series on tipping elements, irreversibility, and abrupt change. These events explore the latest research on tipping points, looking primarily at high-impact, low-probability events.

- The next webinar taking place in June will explore Paleo Climate Insights on Societal Collapse. The aim of these events is to advance knowledge about tipping elements, irreversibility and abrupt changes in the earth system.

- The Global Climate Observing System (GCOS) will organize a large climate observation conference in mid-October 2022, focusing on climate extremes and tipping points.

- Finally, under the leadership of Professor Thomas Stocker, there will be an important short contribution on tipping points and irreversibility to this year’s United in Science 2022 Report, a multi-organizational, high-level compilation of the latest climate science information to be launched in September (forthcoming on WMO page).

We are all here today because we know action is required and needed. The crossing of tipping points in the earth-ocean climate system will impact society, the environment and economies alike across the globe.

This is why the WMO, as one of the parent organizations of IPCC, strongly supports the Swiss initiative for a new IPCC Special Report on Climate Tipping Points and their Implications For Habitability and Resources which will galvanize additional progress in the crucial next years. Thus, WMO will be very happy to be part of the next steps in making this become reality.

Open Discussion

Q: Children and young people’s mental health are particularly impacted by the consequences of climate change. There will be an ever-rising need for mental health support structures, currently lacking in most countries. What are the steps youth and governments can take right now to prepare for these events?

What should the role of the academics and frontline health workers be to take a stance on climate change? How can we convince them to engage in the question in a more political way?

Maria NEIRA: The Department of Environment, Climate Change and Health is collaborating with the Department of Mental Health, looking at how to cope with many countries’ lack of required services. Young health professionals will play a role in that. We are trying to incorporate climate change as a health issue in medical school curricula.

That’s why at COP27 together with the bringing the health arguments and the positive arguments for doing more action using the health as a very strong powerful motivation. We will convene a movement and in defining very clear what could be the next steps. Youth is also key in advocacy, as professional corporations of all type of health professionals are rising and joining WHO on this call for more action on climate change.

This already materialized with demonstrations to raise the health argument in climate change last year at the COP26, but the number of health professional needs to multiply. This argument must be made very powerful because our health depends on the type of actions we take now. Therefore, we are calling for a basic public health treaty.

Thomas STOCKER: The connection between health and climate change is an emerging field deriving from an emerging consciousness of their interlinkages. Several university and institutes are including more and more social and preventive medicine. For example the University of Bern carried out a study last year that demonstrated that 37% of heatwave-related mortality can be attributed to anthropogenic climate change.

It is important that quantitative knowledge base increases substantially, and that means medical people working on large databases to draw from observations from the climate system. These should also be could with physiological and medical information, cohort studies, and more, to increase the knowledge that can then be incorporated into assessment processes such as the IPCC or other bodies that carry out assessment processes.

Alexandra BILAK: The question relates to types of structures and government capacity that is going to be needed to accommodate the effects of climate in the future is very relevant for displacement. Lower income countries are already bearing the brunt of these climate related impacts and the displacement that comes with it, but this is aggravated because they lack the capacity to adequately monitor and track the situation of their displaced citizens and communities over time.

We are investing a lot with our partners to help build adequate governmental structures through improving existing monitoring and reporting systems and connecting the knowledge and the information that exists on displacement to countries commitments under the SDGs. There needs to be much more collective effort and funding, and this represents the biggest gap. The positive side is that governments are showing more ownership and leadership around the issue of displacement and possibly in the public health sector. Now it is a question of investing much more in collecting and compiling good practices that can then be shared with other governments. Hopefully, that will also be one of the focus areas of a future IPCC report.

Q: How would you describe the difference between tipping points and planetary boundaries? Both are often used in international discussions, but this does not always contribute to a clear understanding of the situation.

Thomas STOCKER: Planetary boundaries is a much more overarching concept to demonstrate that through all the changes that man inflict on planet Earth, we are going beyond habitability. Whereas tipping points are processes in the climate system not only global ones as the planetary boundaries, but also regional ones that impact directly on people’s well-being.

Q: How can capture tipping points in a robust way in different models that already exist, such as Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) and Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs)?

Thomas STOCKER: This is an ongoing scientific activity across the hierarchy of models, both from the comprehensive general circulation models that are assessed in CMIP and in IAMs. IPCC has not yet developed scenarios that include tipping points and hence, IAM models have not yet taken up that topic.

Q: How would a special report on tipping points be able to address migration displacement and health issues? When it comes to these topics, the IPCC often relies on existing literature rather than developing new peer-reviewed research, how can this be overcome?

Thomas STOCKER: An IPCC Special Report when commissioned commences the work of hundreds, if not thousands, of scientists collecting available information. IPCC is sort of backward looking on literature that existing but as the example of the special report on extreme events showed, it triggered the scientific community, funders and the world programs of research to address that topic. This has brought a long-lasting value to our knowledge in triggering new research and that can be expected also from such a special report, which will generate knowledge that will be helpful in forthcoming cycles of the assessment at which time, we would hope that tipping points are a standing element in all these assessment reports.

Sebastian KÖNIG: There is a clear need for this topic to be further explored, not only from the science side as a complete picture of tipping points and their significance at the global, regional, and local scales, the financial, displacement and health sides are needed. Switzerland will host an official side event on this topic at the upcoming SBSTTA (Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice) and SBI (Subsidiary Body on Implementation) meeting in Bonn. The agenda for the future entails further exploring also with governments how we can best approach the process to get to a special report by the IPCC.

Eric USHER: It is hard for economic actors today to make sense of the climate science without having credible information for them to understand of physical climate risks and responses to climate change. Thus, bringing together key actors to build that knowledge can be a tipping point in the ability of markets to respond to a changing climate and its changes.

Q: Can you comment further on the mitigating measures of impacts of the tipping points in the climate system in settings that are resource limited?

Maria NEIRA: One of the problems of the health sector is that the cost of the externalities generated by conversion of fossil fuels. Fossil fuels are rarely considered from a health point of view, but every year the global health system spends 5 trillions, for treating patients and taking care of chronic diseases generated by the exposure to the combustion of fossil fuels. It is evident therefore that the end of fossil fuel dependence will generate incredible health benefits. While 400 billions of subsidies are still given to fossil fuels, we are paying consequences in our hospitals.

Alexandra BILAK: IDMC has quantified the financial cost of providing assistance to displaced people today, which right now globally stands at 21 billion dollars. It must be noted that this only encompasses the cost of providing direct humanitarian assistance in the immediate crisis following a displacement situation and does not estimate all the cumulative effects of protracted displacement situations. Despite being a significant underestimate, it is already a remarkable number as it can also represent up to 10% of a country’s GDP, like Syria or Somalia. Thus, the cost of inaction today is going to be much higher in the future.

Q: Do we need to strengthen global monitoring of climate tipping points? For instance by building on advancements in availability of high frequency satellite imagery.

Jürg LUTERBACHER This is really an important point that should be done. So, fully supportive this suggestion that this needs to be done.

Concluding Remarks

Jürg LUTERBACHER: Tipping points are reasons of concerns for all of us as their impacts at local, regional, national, and global scale will be associated with major risks for ecosystem and humans. Therefore, WMO fully supports the initiative for an IPCC Special Report on Climate Tipping Points and their implications for about the ability and resources.

Maria NEIRA: For human health, it is absolutely unacceptable to go beyond tipping points. The health sector supports every initiative working to impede we will never reach that tipping points, because human health will simply disappear.

Eric USHER: In a world of increasing uncertainty, economic actors are looking to the science to help provide them with direction. For a topic like tipping points, I would hope economic actors do not rely on the Twitter sphere to understand implications but look to the IPCC to understand what they can act upon.

Alexandra BILAK: It is difficult to establish a direct causal relationship between climate change and displacement. What we know for sure is that in the future climate change will increase the frequency, the intensity of the hazards and that will increase the risk of future global displacement. So, there is a huge cost involved in not reversing the trends we are seeing today and indeed we have to prevent reaching these tipping points as the implications for global displacement will be huge.

Thomas STOCKER: Policymakers and the public need better knowledge from the host of information that is out there in the scientific literature. That knowledge can be provided by a special report on tipping points carried out by the IPCC in the seventh assessment report. Science and the scientists are waiting to carry out that assessment across all three working groups. The entails not only the natural and the climate science but also the impact and risk science as well as finances, health, and technology.

Sebastian KÖNIG: We must look back more than three million years ago to have a similar situation to the one we are heading towards in our future. We must ensure we know and understand the way ahead and for not crossing the tipping points. For this, we need to have complete assessment.

Video

In addition to the live WebEx and social media transmissions, the video of the event is available on this webpage.

Gallery

Documents

Links

Attribution

The photo for this event “Sea of Frozen Methane in Siberia” is taken by Felton Davis from Flickr (21-08-07).