Event Virtual

Launch and Panel Discussion | Global Criteria to Address Problematic, Unnecessary and Avoidable Plastic Products

01 Feb 2024

14:00–15:30

Venue: Online | Webex

Organization: Nordic Council of Ministers, Geneva Environment Network

Launching the new report from the Nordic Council of Ministers, this event organized within the framework of the Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues provided a platform for stakeholders to explore and discuss possibilities for addressing problematic, unnecessary and avoidable plastic products while drawing on insights from the publication.

About this Session

A new report from the Nordic Council of Ministers focuses on addressing problematic, unnecessary and avoidable plastic products at the global level, in line with the objectives of the upcoming international plastics instrument set out by UN Environment Assembly resolution 5/14. The report notes that over 140 countries have enacted bans or restrictions on specific plastic products, highlighting the need for global criteria to manage not just single-use plastics, but also a wider range of plastic products.

The report is created to support the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) in shaping the plastics instrument. It presents possible criteria for determining plastic products into three distinct classifications: problematic, unnecessary, and avoidable. These classifications are essential towards developing control strategies specific to each. The report’s ultimate aim is to phase out problematic, unnecessary, and avoidable plastic products. The authors suggest options for how this can be achieved under the future global instrument to end plastic pollution by promoting alternate practices or non-plastic substitutes, and by redesigning essential plastic products for safety and sustainability. These core strategies should be based on criteria that are focused on product function, end-use and essentiality.

Launching the new report, this event provideD a platform for stakeholders to explore and discuss possibilities for addressing problematic, unnecessary and avoidable plastic products while drawing on insights from the publication.

Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues

The world is facing a plastic crisis, the status quo is not an option. Plastic pollution is a serious issue of global concern which requires an urgent and international response involving all relevant actors at different levels. Many initiatives, projects and governance responses and options have been developed to tackle this major environmental problem, but we are still unable to cope with the amount of plastic we generate. In addition, there is a lack of coordination which can better lead to a more effective and efficient response.

Various actors in Geneva are engaged in rethinking the way we manufacture, use, trade and manage plastics. The Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues aim at outreaching and creating synergies among these actors, highlighting efforts made by intergovernmental organizations, governments, businesses, the scientific community, civil society and individuals in the hope of informing and creating synergies and coordinated actions. The dialogues highlight what the different stakeholders in Geneva and beyond have achieved at all levels, present the latest research and governance options.

Following the landmark resolution adopted at UNEA-5 to end plastic pollution and building on the outcomes of the first two series, the third series of dialogues will encourage increased engagement of the Geneva community with future negotiations on the matter.

Speakers

By order of intervention.

Erlend DRAGET

Lead Negotiator / Focal Point, INC Plastic Pollution | Ministry of Climate and the Environment, Norway

Walter SCHULDT

Minister, Permanent Mission of the Republic of Ecuador to the United Nations Office and other international organizations in Geneva

Karen RAUBENHEIMER

Lecturer at Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS), University of Wollongong

Niko URHO

Independent Consultant

Llorenç MILÀ I CANALS

Head, Life Cycle Initiative Secretariat, UNEP

Patrick UMUHOZA

Multilateral Cooperation Officer, Rwanda Environment Management Authority

Mahesh SUGATHAN

Senior Policy Advisor, TESS

David CARROLL

External Affairs Director, Plastics Europe

Eirik LINDEBJERG

Global Plastic Policy Lead, WWF

David AZOULAY

Director of the Geneva Office and of the Environmental Health Program, Center for International Environmental Law | Moderator

Summary

Opening Remarks

Erlend DRAGET | Lead Negotiator / Focal Point, INC Plastic Pollution | Ministry of Climate and the Environment, Norway

- Globally, the plastic pollution conversation was initially focused on plastic litter in the marine environment. The sight of plastic items across rivers and beaches was unbearable to many. The fact that plastic pollution is visible has helped to drive this issue to the forefront of the global environmental multilateral agenda.

- Since then, our understanding of the sources and drivers of plastic pollution has grown to include pollution from all plastics throughout the value chain, including microplastics and impacts of related chemicals of concern.

- As a part of a more comprehensive approach to address the full life cycle of plastics, the plastics treaty must have a mechanism that regulates specific plastic products with a particularly high risk of ending up in the environment.

- The scope and utility of the treaty will be hard to grasp if we do not simply ban certain items considered problematic, avoidable and unnecessary.

- The Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee discussions converged on the urgency of addressing plastic products at high risk of being released into the environment. Already over 140 countries have implemented some form of bans or restrictions on certain plastic products and the report presented today is a key knowledge product to inform the INC negotiations.

- Since the Nordic Council published in 2020 a report on what a global treaty could look like, identifying possible objectives, elements, and approaches, various other reports have been developed to explore plastic features such as product design criteria, financing mechanisms, measures to address microplastics, the science-policy interface, as well as the role of regional instruments as it relates to a potential new Plastics Treaty.

- These reports were important in securing the mandate at the fifth session of the United Nations Environment Assembly UNEA 5.2 to start negotiations of the Plastics treaty and are still valuable to inform the global policy discussions as we move forward.

Walter SCHULDT | Minister, Permanent Mission of the Republic of Ecuador to the United Nations Office and other international organizations in Geneva

- Ecuador has implemented legislation on single-use plastic but in some other cases, some measures can also be grounded on other considerations such as safety, sustainability, or even efficiency.

- At the same time, the revised zero draft of the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment (UNEP/PP/INC.4/3) includes – among different options – potential commitments or encourages parties to the future treaty to reduce, restrict the production, sale, distribution, import, or export of plastic products listed in the future annex of the treaty. To identify the basis of certain criteria we need a specific timeline.

- The zero draft also establishes that such measures of reduction or restriction have to be implemented, provided that alternatives or substitutes are available, accessible, and affordable. It also allows exceptions on certain products given that a party has registered it. Additionally, it does not improse limits on any party’s abilities to enact bans or adopt even more ambitious criteria.

- As for plastics with a high risk of environmental leakage, options outlined in the zero draft include national criteria that could be guided by the governing body. This national perspective option includes a very important provision: the determination of the means of implementation to support such measures’ implementation.

- On the other hand, the zero draft also proposes a less ambitious option, which only encourages parties to take measures to gradually reduce the use of this type of problematic and avoidable plastics, identified again based on the availability, accessibility, and affordability of alternatives.

- One of the main challenges is the identification of the relevant criteria or parameters to determine whether certain plastic products are problematic, unnecessary and avoidable and consequently what measures parties should or could adopt to address them.

- This report represents a good starting point for this as it does not stop only in the identification and the provision of criteria for such a selection, but presents potential measures to address them. In addition, it provides some principles and approaches such as the full life cycle, and adopts a flexibility approach to include future new products.

- The report also includes some very important suggestions on the process and institutional arrangements and for governance and decision-making to address these issues. We are very confident this and all previous Nordic Council report will provide useful tools to advance on the zero-draft text negotiations.

Overview by Lead Authors: Key Findings and Recommendations from the Report

Karen RAUBENHEIMER | Lecturer at Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS), University of Wollongong

- The aim of this report and today’s discussion is to support the development of global criteria under the plastics instrument and to establish what the global criteria could entail to support the transition towards sustainable management of problematic, unnecessary and avoidable plastic products.

Scope and Structure of the Report

- We looked only at criteria applicable to problematic plastic products; unnecessary plastic products; and avoidable plastic products and developed a set of criteria for each classification.

- The report first provides a review of current restrictions of products, polymers and monomers. These are listed in section one and expanded in appendix one.

- Section two of the report describes the reasoning behind the selection of the three classifications and criteria sets.

- Section three then lists the potential criteria.

- Sections four and five discuss possible processes and institutional arrangements for listing of products under the plastics instrument.

- This presentation showcases a simplified version of the criteria with some examples of products, while section three of the report provides a table for each set of criteria with further examples and instances of existing regulations and initiatives for each.

Role of the Global Criteria

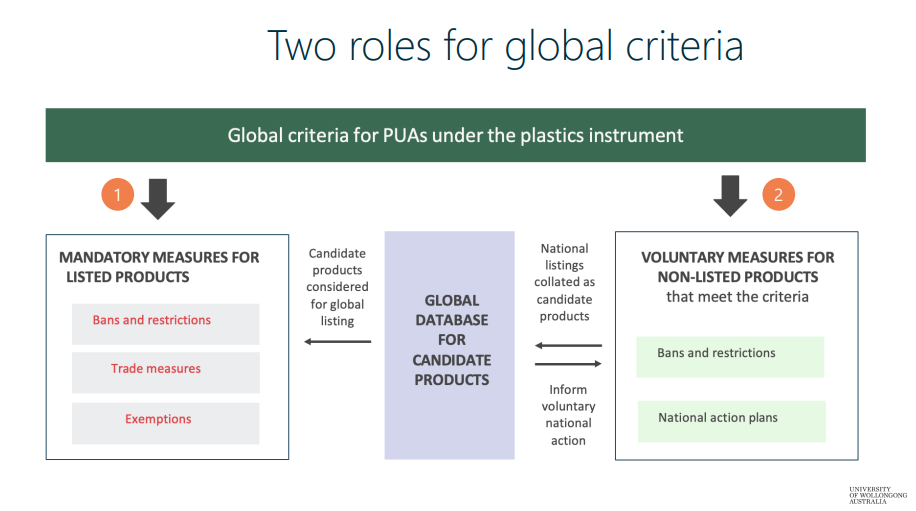

- These criteria could have two main roles in stimulating (a) mandatory measures for listed products; and (b) voluntary measures for non-listed products.

- At the international level, the criteria could provide the basis for identifying, nominating and listing products potentially within annexes to the plastics instrument.

- Managing the plastics products that may not make it to a global listing or are pending that process could be tackled at the national level. Countries could the global criteria to voluntarily identify additional products not yet listed or regulated by the plastics instrument and take national action beyond the obligations established under the instrument.

- Mandatory measures such as bans and restrictions, trade measures and exemptions for specific products or applications on a case-by-case basis would apply to products listed under the instrument.

- Countries could use global criteria to voluntarily identify additional products not listed and strengthen national action beyond the global obligations under the plastics instrument.

- The global criteria could also be used to establish a global database for candidate products. The database could information on products listed nationally and not yet under international obligation and could then serve as a starting point to consider new product listings at the global level and can help stimulate voluntary national action in other countries.

- The report provides a proposal for this database in Appendix One. It shows current actions undertaken, assessing the 141 countries that have banned or restricted some form of plastic products and the 33 countries that have banned or restricted one or more plastic polymers or monomers.

- In some cases, this applies only to particular applications while in most cases this action is limited to single-use plastics and we must go much further than that.

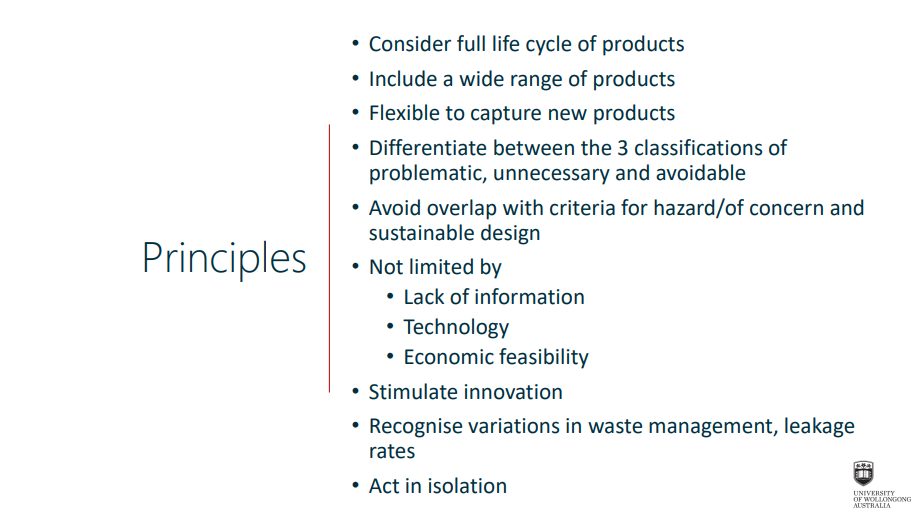

Principles and Definitions

- The classifications of problematic, unnecessary and avoidable plastics products employ different wording from that used in the revised zero-draft text of the plastics instrument and of some of the current reports and voluntary instruments.

- The three classifications help distinguish clearly between the control measures for each regarding removal, reduction and redesign.

- Definitions are purposely broad allowing us to catch a very wide range of products.

- The goal of the avoidable category is not to completely remove the product from the market but rather to reduce the need to produce more of the product. This is where the circularity of approaches are important.

- Based on these definitions, we created a simple design hierarchy which also helps clarify the control measures relevant to each of the criteria sets.

- Products could follow three pathways:

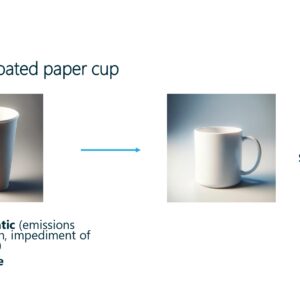

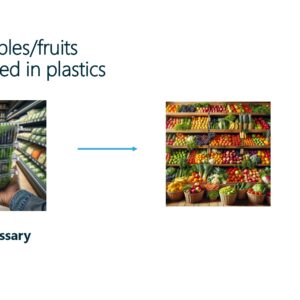

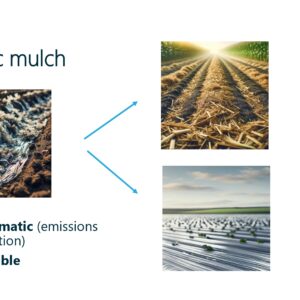

- A product is assessed against the first set of criteria – problematic. If determined to be problematic, the product is then assessed against the second criteria set for unnecessary, where an assessment of whether the product can be removed from the market entirely, without needing to replace it with a non-plastic substitute or an alternate plastic, takes place. If the product does not meet the unnecessary criteria it is assessed against the criteria for avoidable prodcts. If it meets the avoidable criteria, it is replaced with a non-plastic substitute or an alternate practice that reduces the need for the production of that product such as a reuse business model.

- A product is assessed against the first set of criteria – problematic. If determined to be problematic, the product is then assessed against the second criteria set for unnecessary, where an assessment of whether the product can be removed from the market entirely, without needing to replace it with a non-plastic substitute or an alternate plastic, takes place. If the product does not meet the unnecessary criteria it is assessed against the criteria for avoidable prodcts. If it meets the avoidable criteria, it is replaced with a non-plastic substitute or an alternate practice that reduces the need for the production of that product such as a reuse business model.

- Problematic products may require redesign of the product to ensure that alternate practices meet safety requirements for environmental and human health.

- The control measures for the removal of unnecessary products from the market or the replacement of avoidable products and the redesign of those products that will stay on the market can all contribute to the goal of reducing the production of plastic products. The criteria for redesign of products would help achieve the ultimate goal of sustainable and safe management of plastics.

- The identification of appropriate control measures for a product may require two qualifying factors. For products deemed problematic, their removal is warranted if they are also classified as unnecessary. If the product problematic products are not unnecessary they may be avoidable and the preferred control measures would be replacement with non-plastic substitutes or alternate practices.

- They may also need to be redesigned to make them safe and sustainable. If a problematic product is not unnecessary or avoidable, it would still need to be redesigned to remove the problematic elements.

Niko URHO | Independent Consultant

The Criteria

- The goal of these criteria for determining unnecessary products is to move us closer to their elimination from the market. This includes two main criteria:

- Availability or potential for availability of alternate practices that do not require plastic.

- Availability or potential availability of alternate designs that remove plastic components in other words the plastic product is unnecessary because it lacks an essential function and can be therefore removed without the need for replacement.

- The criteria for avoidable plastics refers to the product with an essential function where the demand for the product can be reduced or removed. It aims to reduce the need to produce plastic products from primary materials. It includes three criteria:

- Availability or potential for availability of alternative practices that reduce the need for the new versions of the products in its plastic form.

- Availability or potential for availability of non-plastic substitutes that reduce the need for the product.

- Availability or potential availability of alternate designs that reduce the need for new versions of the product.

Examples of Plastic Products

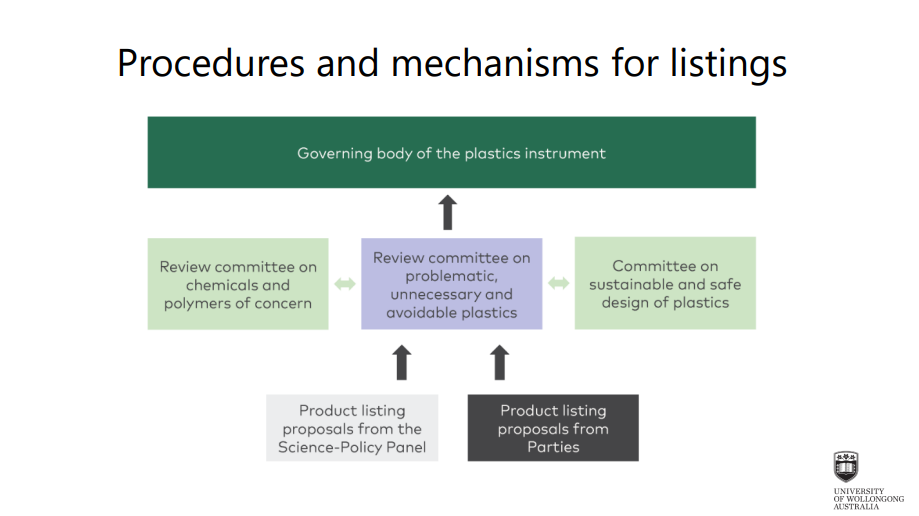

Procedures and Mechanisms for Listing

- The process of listing problematic, unnecessary, and avoidable plastic products under the plastics instrument includes four main phases (starting from the bottom):

Conclusions

- The model of global criteria aims to provide a flexible approach to to capture a wide range of both existing and new PUA plastic products.

- This listing should be proactive and based on scientific review, including the use of the lifecycle assessment.

- The product listing needs to be reassessed and adjusted periodically, following a type of adaptive management approach.

- Capacity building is needed for effective involvement in the proposal of listing of the review process and for implementation.

Keynote Address | The Global Impact of PUAs and the Challenges in Managing them

Llorenç MILÀ I CANALS | Head, Life Cycle Initiative Secretariat, UNEP

- The plastics economy is highly problematic. Problems are related to product design and the structure of the economy. In some cases, plastic packaging loses 95% of its value to the economy after a single use, and this is by design, not an accident.

- While the plastic economy generates revenues estimated between $ 600 and 700 billion per year, the social and environmental costs associated with plastic pollution are also along this value but unaccounted for. We calculate this cost along the life cycle of plastic products to be $ 300 – 600 billion per year and potentially much higher.

- Plastic pollution is deeply embedded in the way the plastics economy works, and a holistic systems change is needed to solve this crisis. We cannot solve this by banning specific products or improving recycling infrastructure.

- UNEP’s report Turning off the Tap: How the World can End Plastic Pollution and Create a Circular Economy claims all levers must be pulled at once. We must eliminate the plastic we do not need by defining which products are problematic, unnecessary avoidable. These criteria can also help in innovating and delivering products that can be reusable, recycled or even made with a different material. We also need to ensure that there is a safe disposal of everything else that cannot stay in the economy any more or that has already been lost to the economy or is not yet designed to be circular, we need to make sure that it does not leak into the environment.

- The top priority is to reduce the size of the problem by eliminating problematic, unnecessary, and avoidable plastics and shifting significantly towards reuse. The report provides criteria to select such plastics, including excessive headspace, products not fulfilling essential needs, and those containing chemicals of concern.

- Innovative opportunities to reduce unnecessary plastic consumption, such as transitioning from single-use to reusable products must be carefully assessed against potential knock-on effects. UNEP estimated that 30% of plastics used in short-life products could be reduced starting by 2040.

- Recent estimates, including a previous study by the Nordic Council of Ministers, go beyond this amount. It is possible to reduce the amount of plastics maintaining the level of functionality this sector provides.

- Attention to detail is essential in defining problematic, unnecessary, and avoidable plastics and ensuring that replacements offer a reduction in impact and provide benefits. Criteria are very useful to facilitate the decision-making processes but must be based on a life-cycle assessment. LCAs should also be complemented with safety and socioeconomic analyses to avoid regrettable substitutions.

- While plastic leaks in the environment are a recognized problem, not all plastic substitutes are necessarily avoiding the issue.

- Establishing strong LCAs is required by UNEA resolution 5/14 and the establishment of conditions for the LCAs to be fully comparable could use the assistance of a scientific body.

Panel Discussion | Exploring Challenges, Opportunities & Diverse Perspectives on PUA Plastics

Mahesh SUGATHAN | Senior Policy Advisor, TESS

- TESS welcomes the report’s recognition of trade-related measures among mandatory control measures that could be deployed to address listed problematic, unnecessary, and avoidable plastic products.

- TESS recently published a policy brief exploring experiences and potential for trade-related measures and cooperation to support the restriction and elimination of PUA products.

Substitution

- Substitution through non-plastic products can play a key role in addressing the challenge of replacing avoidable products together with alternative designs and practices.

- In its system change scenario, the Pew Charitable Trusts note that a substitution option could significantly reduce marine plastic pollution by 2040. For example, they estimate that replacing plastic with substitutes such as paper, coated paper, and compostable could cut plastic waste by 17% or 71 million tons by 2040.

- The relevance of substitution is recognized in the zero-draft of the plastics treaty, by INC members in their submissions and in the dialogue on plastic pollution at the World Trade Organization, which involves 76 WTO members. The ministerial statement of the DPP calls for sharing best practices and experiences in promoting environmentally sustainable and effective substitutes and alternatives, as well as identifying technologies for environmentally sustainable and effective substitutes and alternatives. The text also provides references for supporting developing countries in their efforts to expand trade in environmentally sustainable and effective substitutes and alternatives, as well as developing local capacities.

- According to the statement, effectiveness should be both cost-effective and function-effective.

- Non-plastic substitutes may encompass different materials and they must be distinguished from plastic alternatives

- No official definition of plastic substitutes exists but the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) one is a starting point:

Plastics substitutes include natural materials from mineral, plant, animal, marine or forestry origin that have similar properties to plastics. They do not include fossil fuel-based or synthetic polymers, bioplastics, and biodegradable plastics. Plastic substitutes should have a lower environmental impact along their life cycle (e.g., natural fibres, agricultural wastes, and other forms of biomass). Depending on the case, they should be biodegradable/compostable or erodable, and should be suitable for reuse, recycling, or sound waste disposal as defined by national, regional regulations or in internationally agreed definitions. They can include by-products. Plastic substitutes should not be hazardous for human, animal, or plant life.

- In terms of properties of non-plastic substitutes, lifecycle considerations are very important. The application and use can vary from country to country. For example, in many cases, infrastructure for reuse and refill models may not exist. That opens to the question of whether different solutions should be employed where this occurs.

- Important discussions should also take place around which non-plastic substitutes should be preferable.

- Definitions will be essential. In the context of the WTO DPP, delegates have already made references to the need to develop definitions of specific terms related to non-plastic substitutes, such as plastic alternatives, reusability, compostability, recyclability, and biodegradability.

- The promotion of non-plastic substitutes must be balanced with measures to reduce problematic, unnecessary, and avoidable plastic products, which in turn could indirectly incentivize a lot of these substitutes. When this additional layer of measures or regulations to promote the right kind of non-plastic substitutes is in place, additional regulation.

- There are examples of well-established non-plastic substitutes that countries have been producing and exporting such as jute fibers used as packaging material for certain commodities like cocoa beans and coffee.

- TESS works on how trade and trade policies are relevant to the promotion of environmentally sound and effective non-plastic substitutes. We highlight what policy measures and types of support would be necessary to promote non-plastic substitutes, including trade-related policies. These could include:

- addressing tariff and non-tariff barriers to non-plastic substitutes;

- appropriate domestic regulations,

- tax and procurement-related incentives;

- eliminating or reducing subsidies that favor plastics;

- facilitating investments in domestic productive capacity;

- environmentally sound waste management, including for certain kinds of non-plastic substitutes;

- international cooperation on regulation standards and conformity assessments.

- The WTO DPP also looks into financing and aid for trade measures to enable countries to deploy non-plastic substitutes effectively and economically and at scale. Often deployed non-plastic substitutes are limited in terms of how much they can be scaled up.

- To switch to non-plastic substitutes, we also have to make it easier to track some of the trade flows. Trade policymakers who might want to incentivize some of these non-plastic substitutes with trade policy need to understand who is producing them, how much is being exported, and how are they classified within the global customs classification.

- More work on clarifying such codes could help policymakers, customs officials, and researchers.

David CARROLL | External Affairs Director, Plastics Europe

- Plastics Europe produced various reports – ReShaping Plastics or Plastics Transition Roadmap – that address transparency efforts around circularity and production of plastics. These aim to be a source of information on what applications plastics and polymers are used in and what are their end-of-life management options. It is important to stress that Europe’s industry, legislation and approach to plastic pollution differ from the rest of the world, making these assumptions applicable more to the European context.

- In terms of problematic and avoidable plastics, Plastics Europe supports the inclusion of the whole life cycle of plastics. When it comes to problematic and avoidable, we want a criteria-based approach, looking at unnecessary and problematic plastics applications, such as a decision tree-type assessment tool. We are against arbitrary listings or negative lists of products and decisions to ban them globally.

- To address PUAs sustainably, it is important to start with a series of questions and principles based on the waste hierarchy:

- Circularity: what is the current status of the application? Is there a possibility for prevention or reuse? If not, is there a possibility for recycling? What are the recycling rates?

- State of the waste management around that particular application.

- Socioeconomic value of that application.

- A comprehensive robust assessment is necessary. This must be done through scientific assessment, and stakeholder consultations, including a broad base of perspectives. Such assessment should evaluate the impacts of product removals and of their alternatives, whether that be a reuse system or a substitute material. It is also important to evaluate the environmental benefits of such substitutions and the scale at which they could be applied.

Global versus National Applications

- Transformation of the global plastic pollution situation should be carefully assessed against specific national needs and infrastructure availability.

- From the plastics treaty, Plastics Europe would like to see a global methodology to identify and address problematic applications. This could be shaped as a global mandatory harmonized criteria, to be read alongside other global mandatory circularity provisions, such as eco-design and design for recycling criteria.

- On the other hand, assessments must take place at the national level, and measures must be implemented in the national action plans. This is the only way to look at the socioeconomic needs and the waste management situation as some applications that may be fundamental in one country may be unnecessary luxury items in another.

- As representatives of the European industry, we do not want to be the only ones to take action or the only ones who face legislation, therefore a global level playing field must be established.

Roadmap to Circularity

- Efforts must prioritize items with the highest likelihood of leakage. This will allow us to pinpoint which applications to phase out while at the same time working to make circular those plastics whose applications are valuable.

- This framework could apply to all materials and avoid regrettable substitution, allowing to achieve sustainable consumption, which in turn leads to the sustainable production of plastics.

- A positive investment climate must be created as transitioning away from PUAs requires enormous investments. Plastics Europe Transition Roadmap estimates a minimum of 235 million above business as usual only for Europe.

- Industry wants to see impact-assessed science-based policy, not arbitrary decisions to ban certain products without looking at alternatives as this will erode business confidence and halt innovation. Policy must clearly present data on chemicals used and their environmental impacts.

Eirik LINDEBJERG | Global Plastic Policy Lead, WWF

- It is important to remember the reasons why we are negotiating this treaty. Plastic pollution is an accelerating global threat to the environment. We identified plastic pollution in every single ecosystem on the planet. If we do not act now, plastic pollution will triple by 2040. This treaty must substantially reduce plastic pollution and eventually end all plastic pollution.

- Approximately 70% of the plastic that leaks into the ocean is some form of single-use plastic, 20% being microplastic and 7% fishing gear. The criteria set out in the report should take us closer to eliminating a large enough part of plastics that is dominating the leakage, which are short-lived single-use plastics.

- WWF is present in about 100 countries around the world. Working on the ground, in particular with communities at the city level and in Southeast Asia and Africa, to set up solutions for solving the plastic pollution issues teaches us that it is an uphill battle. We need stronger measures at the global and national levels, and to go up the waste hierarchy.

- Cities, communities and governments are overwhelmed with plastics flowing onto their market and that is difficult to manage properly, which is why it often ends up leaking into the environment. Going up the waste hierarchy starts with prevention and avoiding certain types of plastics. This report can be instrumental in supporting the necessary technical clarity for PUAs and chemical additives to be phased out and eliminated at a global scale to phase out and eliminated.

- WWF’s previous work on high-risk plastics products came to some of the same conclusions as the Nordic Council Report. We defined high-risk plastic products as a function of the harm a product causes and the probability of it leaking into the environment, both elements are also in the criteria list of this report providing stronger alignment.

- In the report, we broke plastics down into product groups, and the tools provided in the Nordic Council report provide a framework for continuing to break it down. These should all support the treaty in adopting measures that are specific enough and that allow the elimination of PUAs products.

- The treaty must establish a minimum requirement for plastics and that it establishes global bans on the most problematic, unnecessary, and avoidable plastic products. Knowledge to find large groups of products that would merit a ban on a global level is already available. Such ban should take place not only at the national level as many of these policies are more effective and easier to implement – in particular for developing countries – if done at a global level.

Conclusions

Walter SCHULDT | Minister, Permanent Mission of the Republic of Ecuador to the United Nations Office and other international organizations in Geneva

- The negotiations for a plastics instrument have no comparison with any other instrument that aims to address several cross-cutting issues and that offers the possibility to still halt a pollution threat.

- This report as well as others that will be published in the intersessional period must have a real use in the negotiation. All participants to the negotiations should bring such research to the negotiating table and beyond in other channels, including the Science-Policy Panel on Chemicals, Waste and Pollution Prevention, the discussions under the WTO, under the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions and at the World Health Organization.

- INC-4 is soon upcoming and everyone is invited to get deep into this report and make use of these suggested options of criteria for the selection termination of avoidable, problematic, and unnecessary plastic products.

Erlend DRAGET | Lead Negotiator / Focal Point, INC Plastic Pollution | Ministry of Climate and the Environment, Norway

- Discussions must always pay attention to how they relate to the overall picture. We need to dive deep into a specific part of the treaty and have discussions that allow advancing.

- There is unanimous support for developing global criteria and an approach to identify possible measures for specific products, while keeping flexibility at the national level.

- The INC timeline is very stringent and now is the time to clearly define what the treaty text should include in terms of specific regulations and obligations; and the mechanisms that allow strengthening our approach over time.

- Establishing criteria, identifying actions for specific products and implementing a life cycle assessment of different products in different contexts are elements of a long-term approach necessary in the treaty. To this end, at INC3 Norway proposed establishing dedicated programs of work.

Highlights

Video

Livestream on Webex.

Documents

- Global criteria to address problematic, unnecessary and avoidable plastic products | Full Report

- Presentations made during the event

Links

- Nordic Council of Ministers

- Plastics and the Environment

- Towards Plastic Pollution INC-4

- Nordic Council of Ministers Publications

- Options for Trade-Related Cooperation on Problematic and Avoidable Plastics: Building on Existing Experiences with Single-Use Plastics | TESS | 13 November 2023

- The Plastics Transition: Our industry’s roadmap for plastics in Europe to be circular and have net-zero emissions by 2050 | October 2023

- Turning off the Tap: How the World can End Plastic Pollution and Create a Circular Economy | UNEP | May 2023

- Breaking down high-risk plastic products assessing pollution risk and elimination feasibility of plastic products | WWF | May 2023

- Reshaping Plastics: Pathways to a Circular, Climate Neutral Plastics System in Europe | Plastics Europe | April 2022