Event Virtual

Science-Policy Interface for Plastic Pollution | Report Launch

This event, launching the report "Science-Policy Interface for Plastic Pollution" by GRID-Arendal, was organized within the framework of the Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues, in the run-up to the third session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment (INC-3) taking place from 13 to 19 November 2023, in Nairobi, Kenya, and the second session of the ad hoc open-ended working group to prepare proposals for the Science-Policy Panel to Contribute Further to the Sound Management of Chemicals and Waste and to Prevent Pollution, taking place in December 2023.

About this Event

A new report – Science-Policy Interface for Plastic Pollution – published by GRID-Arendal and authored by Karen Raubenheimer and Niko Urho, aims to identify scientific and technical functions relevant to the effective functioning of the global plastics instrument, which is presently undergoing intergovernmental negotiations. It considers how the work of the Science-Policy Panel to contribute further to the sound management of chemicals and waste and to prevent pollution and the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution can interlink and complement each other, as well as ensure smooth collaboration with other relevant scientific bodies.

Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues

The world is facing a plastic crisis, the status quo is not an option. Plastic pollution is a serious issue of global concern which requires an urgent and international response involving all relevant actors at different levels. Many initiatives, projects and governance responses and options have been developed to tackle this major environmental problem, but we are still unable to cope with the amount of plastic we generate. In addition, there is a lack of coordination which can better lead to a more effective and efficient response.

Various actors in Geneva are engaged in rethinking the way we manufacture, use, trade and manage plastics. The Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues aim at outreaching and creating synergies among these actors, highlighting efforts made by intergovernmental organizations, governments, businesses, the scientific community, civil society and individuals in the hope of informing and creating synergies and coordinated actions. The dialogues highlight what the different stakeholders in Geneva and beyond have achieved at all levels, present the latest research and governance options.

Following the landmark resolution adopted at UNEA-5 to end plastic pollution and building on the outcomes of the first two series, the third series of dialogues will encourage increased engagement of the Geneva community with future negotiations on the matter.

Highlights

Speakers

By order of intervention.

Walter SCHULDT

Permanent Mission of the Republic of Ecuador to the United Nations Office and other international organizations in Geneva

Michel TSCHIRREN

Head, Global Affairs, Federal Office for the Environment, Switzerland

Karen RAUBENHEIMER

Lecturer at Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS), University of Wollongong

Niko URHO

Independent Consultant

Ana Paula DE SOUZA

Human Rights Officer, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

Sam ADU-KUMI

Executive Director, EnviroHealth Consult (EHC) and National Expert, Chemicals and Waste, Ghana

Christos SYMEONIDES

Clinical and Research Specialist, Minderoo Foundation

Amila ABEYNAYAKA

Policy Researcher, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Japan | Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty

Jacob KEAN-HAMMERSON

Ocean Campaigner, Environmental Investigation Agency

Peter HARRIS

Managing Director, GRID-Arendal | Moderator

Summary

Walter SCHULDT | Permanent Mission of the Republic of Ecuador to the United Nations Office and other international organizations in Geneva

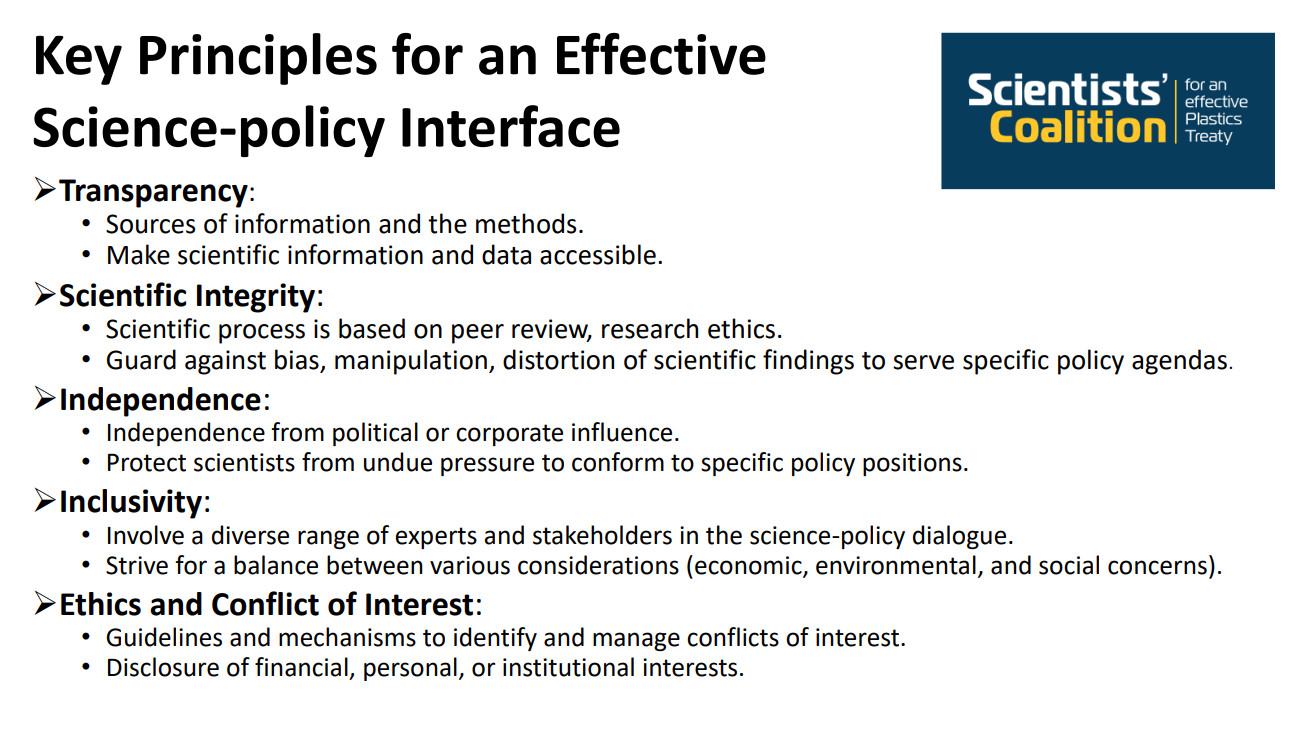

- Science policy interfaces are a key component for decision-making. We should all promote the establishment of permanent mechanisms or spaces for adequate interaction between scientists and other actors in different processes of policymaking. Such interaction should allow for transparent exchange of information; and identification of gaps, challenges, opportunities, priorities and concrete solutions.

- In some cases, that exchange of information may include also support in terms of communication or outreach which can be operationalized in different ways.

- SPPs can provide member states and stakeholders with the most relevant scientific and technical information that is needed to implement a multilateral environmental agreement and review its efficiency. In terms of review, a clear example is the Global Stocktake under the Paris Agreement which will provide the first general overview and assessment of its efficiency in the upcoming meeting of the UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties.

- Assessing whether a science-policy interface (SPI) operates best as an independent intergovernmental body or subsidiary body of the governing body of an MEA depends on the context. This report will provide examples and lessons learned to decide which lessons and best practices could be implemented.

- The composition of this mechanism must guarantee the inclusion; and representativity of all the relevant stakeholders and of people who are in vulnerable situations. SPIs must provide access and participation in the and recognition of resolutions of different bodies such as the General Assembly; the Human Rights Council, the Escazu Agreement, and the Aarhus Convention.

- We need to ensure that these mechanisms or spaces operate under principles of inclusivity, access to information, credibility, effectiveness, human rights-based approach, integrity, objectivity, the precautionary principle and impartiality.

- SPI mechanisms must have in place provisions or principles on conflicts of interest. The IPCC provides an example of a conflict-of-interest committee; the Stockholm Convention has adopted a procedure for dealing with conflict of interest; and article 5.3 of the World Health Organization framework convention on Tobacco Control bans the participation and influence of the tobacco industry. The advantage is that we don’t need to start from scratch.

- The United Nations Environment Assembly Resolution 4/8 asked to prepare an assessment of all the options for strengthening the science-policy interface and we know that among those options a key one was reflected in resolution 5/8 which affirms that the future SPI should be an independent intergovernmental body able to deliver policy-relevant scientific evidence without being policy prescriptive.

- The functions of the SPI will benefit the plastic the future plastic treaty for the identification of issues of relevance, conduction of assessment, facilitation of information sharing capacity building, and financial assistance.

- UNEA resolution 5/14 also provides key provisions: the possibility for the INC to consider a mechanism to provide policy-relevant scientific and socio-economic information and assessment related to plastic pollution. It has other provisions as an assessment of periodic progress, assessment of effectiveness, and economic assessments, among others.

- It is expected that the future instrument will consider the best available science, traditional knowledge, and knowledge of indigenous peoples as well and best practices from all the different settings. This has been somehow missing so far as the INC has been focused on urgent matters but a potential dedicated specific mechanism on SPI for the treaty will be relevant for that.

- Ecuador is actively engaged in the INC process as our member of the bureau and incoming INC Chair

Luis Vayas Valdivieso has been already engaging with the scientific community. We have two members in the group of experts that was convened by the UK and Brazil and have been co-sponsoring resolutions and decisions to strengthen the provision of capacity-building science-based assessment and research including in relation to pollution from plastics.

Michel TSCHIRREN | Head, Global Affairs, Federal Office for the Environment, Switzerland

- Switzerland has been very active in further strengthening the science-policy interface to allow international policy decisions to be based on sound science. Switzerland is an active actor in bodies such as the IPCC the IPBES or the IRP and plays a strong role in the establishment of the new science-policy panel on chemicals, waste, and pollution.

- It is important to speak about science to policy and policy to science in the context of the triple planetary crisis. We need robust science to make good decisions and transform these into good policies.

- The scientific basis needs to be policy relevant but not policy prescriptive and in the context of plastic pollution, this means that the new SPP on chemicals, waste and pollution will have to hear which scientific mappings and assessments are needed.

- The report presented today can help in understanding the scientific and technical needs based on existing UNEA resolutions and learning from existing MEAs.

- Listening to the INC process will allow identifying which are the policy questions that scientific work needs to address. The report will also help to inform about the initial background to kick off the discussion on possible links between the science policy panel on chemical waste and pollution and the upcoming plastic treaty. Once this is clear it will be easier to assess if and what the plastics treaty would need in terms of scientific committees.

- For example, on the day-to-day implementation of the treaty, the science-policy panel on chemical, waste and pollution could identify potential chemicals, polymers and products of concern through its horizon scanning exercise and inform the treaty about potential review and make recommendations on listing or amendments

- This report can inform the open-ended working group process of the science-policy panel about what kind of demands could come in the future from different MEAs or other bodies.

Peter HARRIS | Managing Director, GRID-Arendal | Moderator

- The 1963 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Karl Ziegler and Giulio Natta for their remarkable innovation in the creation of a long polyethylene chain out of a small chemical monomer ethylene. The “age of plastics” had begun and this ground-breaking development set the stage for the widespread use of plastics, changing our world in unimaginable ways.

- Sixty years later the extensive use of plastics and their products is posing a threat to human health and the environment. The situation has reached a critical juncture where we need to plan our future based on scientific evidence and knowledge.

- The milestone resolutions adopted by the fifth session of the United Nations Environment Assembly concerning the establishment of a Science-Policy Panel on chemicals, waste and pollution, and mandating intergovernmental negotiations towards a global legally binding instrument to end plastic pollution attests to the world’s attention to solving the problem of plastic pollution.

- In this context, GRID-Arendal together with two lead authors Niko Urho and Karen Raubenheimer, embarked on the preparation of the report. It aims to provide a sound critical and timely contribution in addressing the scientific and technical support needed by decision-makers to develop an effective global plastic instrument.

Karen RAUBENHEIMER | Lecturer at Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security (ANCORS), University of Wollongong

Possible Functions of the Science Policy Interface For Plastic Pollution

- Science-policy interfaces are defined as “social processes that encompass relations between scientists and other actors in the policy process”. They allow for exchanges and co-evolution and their primary aim is to enrich the decision-making process.

- Any communication of knowledge should be policy-relevant and policy-prescriptive and should provide solution-oriented assessments. Communications must allow decision-makers to balance competing priorities.

- Science-policy interfaces can perform a spectrum of functions and assist in large-scale assessments such as the Global Environmental Outlook.

- The fundamental role of an SPI is to provide member states and stakeholders with the scientific and technical information needed to implement agreements and to review them.

- SPIs may operate as an independent intergovernmental body or as a subsidiary body of the governing body to the agreement.

- Credibility, and legitimacy are widely recognized as foundational to any science policy interface. The SPI for plastic pollution would include functions needed to support parties to the new plastics instrument and those that will be carried out by the new SPP on chemical waste and pollution.

- Both these and the SPIs of other agreements could complement the plastics instrument.

Functions of the SPIs

We grouped the ten suggested science policy functions across four phases of the policy cycle with cross-cutting functions. Grouping them across the policy life cycle helps understand the nature of the outputs that are needed in each phase.

1) Agenda setting. Problem recognition and issue selection are key but this must be based on scientific and technical information. Horizon scanning is important to help detect early signs of change that are not yet on the policy radar. In the context of plastics, this can include risks related to novel entities; legacy plastics, and new technologies and practices. Horizon scanning should be distinguished from foresight which is a broader concept that aims to evaluate possible futures and promote the desired outcomes.

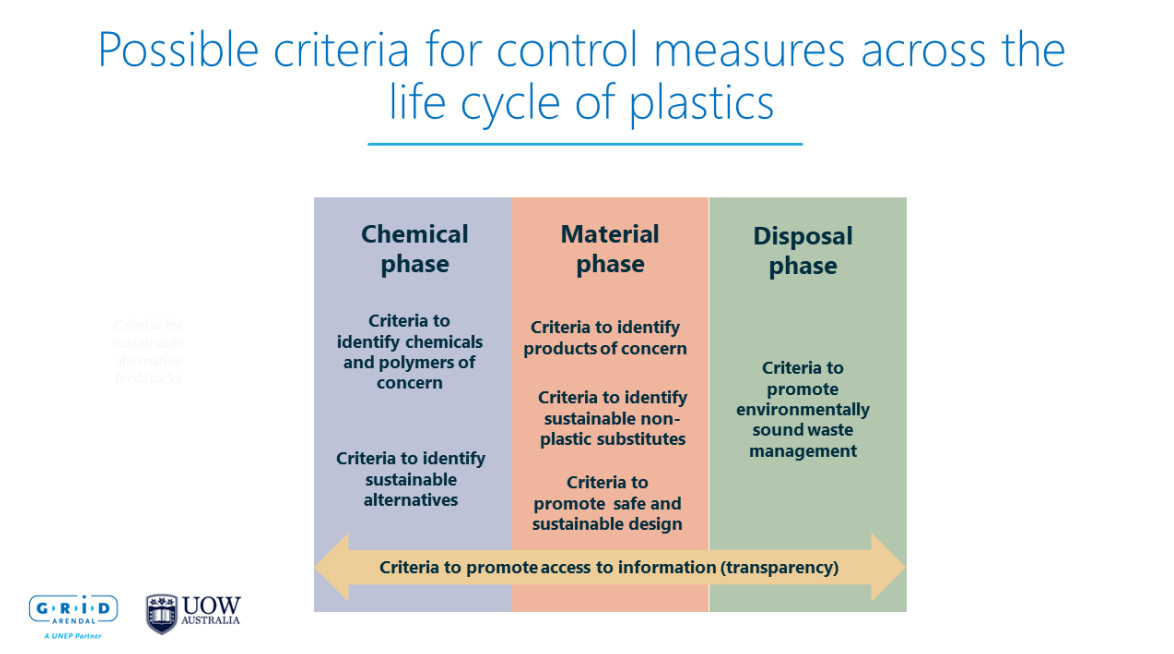

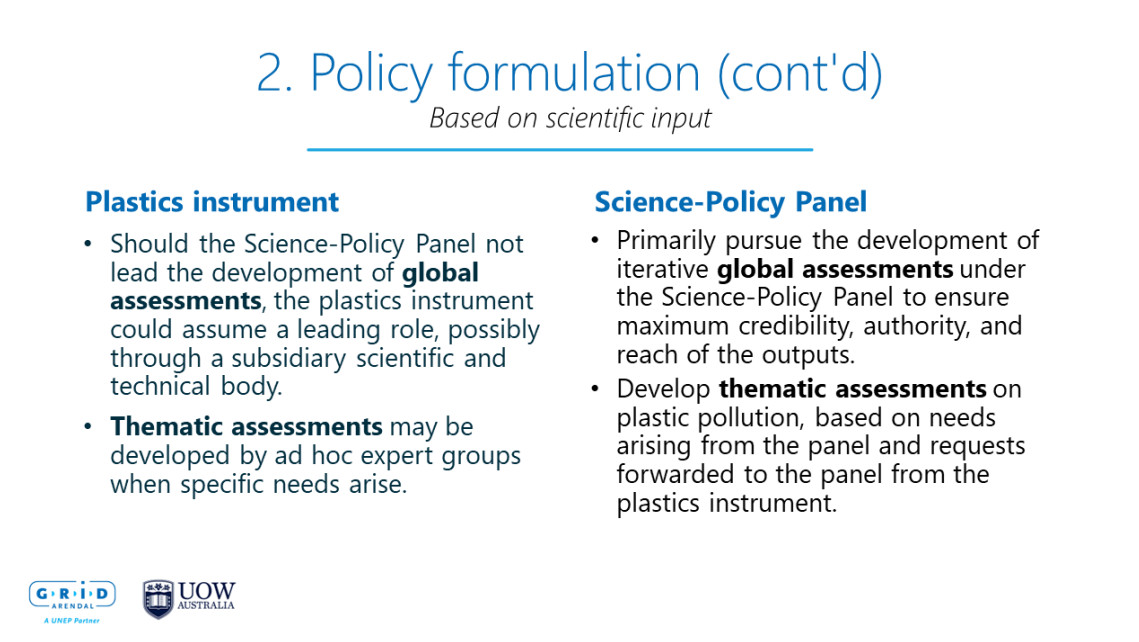

2) Policy formulation. Policies are developed based on scientific inputs. The scientific criteria for control measures can play an important role and help give effect to core control measures of the plastics instrument. Such criteria can be developed to identify chemical polymers; products of concern; sustainable alternatives and non-plastic substitutes to promote safe and sustainable design to promote environmentally sound waste management and access to information or transparency. The function of assessment of scientific technical and socioeconomic information focuses on aggregating and assessing existing research rather than conducting new research. Addressing the plastic pollution crisis more comprehensively would also benefit from global assessments that are iterative and address both the environmental and human health aspects but thematic assessments can also be conducted as needed.

- Strong scientific support is needed in the development of such criteria as well as the review of chemicals polymers and products of concern.

3) The implementation phase focuses on government action, backed by strong scientific and technical support. Policy support tools are needed to enhance compliance and implementation. These could include technical guidelines best available techniques and best environmental practices as well as toolkits. Such tools can particularly benefit developing countries that often lack the resources needed to implement agreements.

- Knowledge management mechanisms can provide a centralized platform to manage and present data. This could include the development of a digital database for data on chemicals polymers and products of concern; knowledge management hubs for visualizing progress; and catalyzing of knowledge generation which is needed to ensure the availability of credible scientific information.

- Ensuring the availability and accessibility of relevant and reliable scientific information especially from developing countries is a pressing challenge.

4) Evaluation. Assessment of progress and effectiveness requires significant scientific and technical input. The monitoring of global progress requires scientific and technical support for developing and updating indicators and harmonizing methodologies for data collection. This includes monitoring plastic flows; leakage; concentrations of plastics in biota and human populations and determining greenhouse gas emissions across the life cycle of plastics.

The evaluation of effectiveness is also needed to understand the impact of policy interventions in solving the problem.

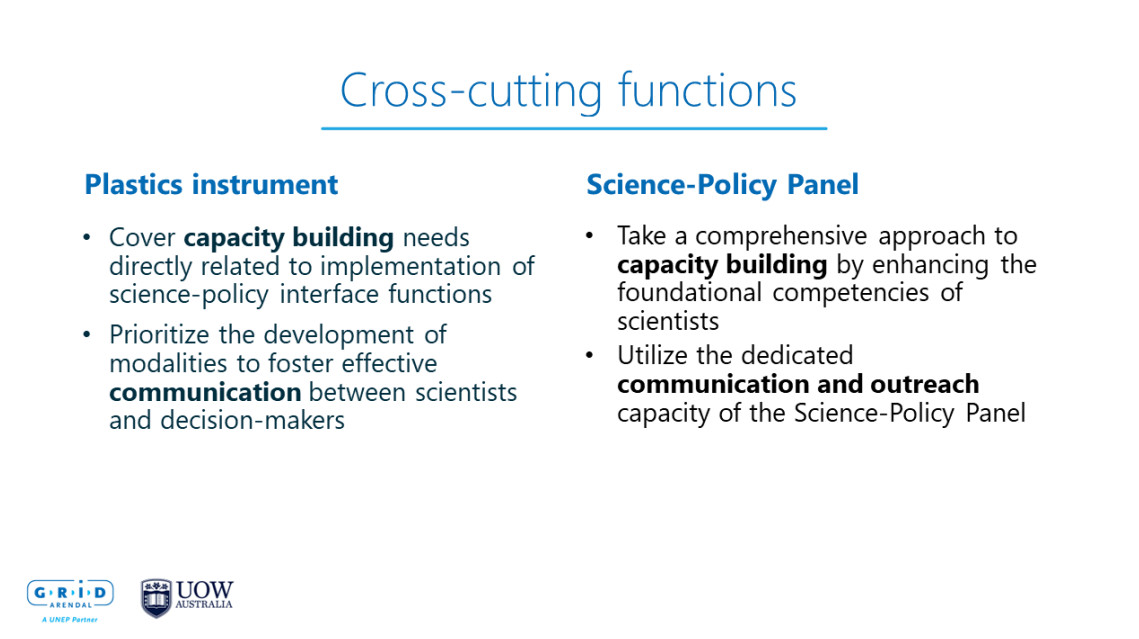

- Cross-cutting functions address two or more phases of the policy cycle. This includes capacity-building; communication and outreach. Enhancing capacities is crucial for amplifying the reach and impact of initiatives and can be linked to all the other functions described here so far communication and outreach are also needed to help decision-makers and to make more informed decisions but also to inform the public.

Niko URHO | Independent Consultant

Possible Institutional Approaches to Realize the Science Policy Interface Functions For Plastic Pollution

The possible division of labor between the science-policy panel and the plastics instrument can be best understood with an overview of the science-policy landscape for plastic pollution.

- Cooperation with the science-policy panel is important to ensure that the plastics instrument will benefit from independent scientific advice across the policy cycles. Cooperation with the scientific and technical bodies under MEAs is important and concerns MEAs in the climate, chemicals and waste and biodiversity clusters as some of these scientific bodies have already initiated work streams on plastic pollution. Cooperation is needed to enhance with other relevant scientific science policy interface bodies and sectoral multilateral bodies that are engaged in scientific and technical work such as in the areas of trade, human health socioeconomic and human health issues.

Science-policy Interface Mandates

- The proposed division of labor is grounded on the science-policy mandates of the science-policy panel outlined in UNEA resolution 5/8 and the plastics instrument outlined in resolution 5/14.

- Most of the functions are explicitly mentioned by one or both resolutions and if not, they are indirectly linked to other functions.

- Agenda-Setting Phase

A predominant role is envisaged for the science-policy panel that has a horizon scanning function aiming to identify issues of relevance to policymakers including those emerging threats.This function could help identify potential products, polymers, and chemicals of concern. The provision of evidence-based options would help in policy formulation. - Policy formulation phase

The use of scientific criteria for control measures could help to provide scientific advice to facilitate informed decision-making. It can be instrumental in closing the governance gap in the upstream phase of the plastics value chain. We recommend the development of a scientific and technical body on chemical, polymer and product safety. Tasks could include:

- Assessment is an important function to support policy formulation. It could include the development of global assessments, which could in turn increase the credibility of the outputs due to the panel’s independent and authoritative role.

- If global assessments cannot be prepared by the panel then a possible dedicated body under the plastics instrument could take over.

- This would follow the example of the Montreal Protocol which has a scientific assessment panel and an environmental effects assessment panel.

- Both the SPP and the plastics instrument could develop thematic assessments as needs arise.3. Implementation Phase

- Practical aspects requiring scientific and technical support are the development of policy support tools, to take place mainly under the plastics instrument either through ad-hoc expert groups or through a subsidiary body on scientific and technical advice.

- The SPP is not explicitly mandated to develop policy support tools but it could potentially assist in certain areas following the examples of the IPCC and IPBES.

- Knowledge Management systems, although not mentioned in the UNEA resolutions, could be developed by either body. Spearheaded by the SPP, such systems might cover all forms of chemicals and pollution making plastic pollution a subset of the broader environmental agenda. Alternatively, if the plastic instrument takes the lead, the secretariat of the instrument could be tasked to focus exclusively on plastic pollution.

- Catalyzing knowledge generation is a shared function between the bodies. The Plastics instrument might play an important role in powering institutions at various levels to undertake research while the SPP would help to identify research gaps and direct future research.

4. Evaluation Phase

- The plastic instrument plays a central role. Scientific experts can contribute to the development of an indicative framework alongside standardized methodologies for data collection to enable comprehensive global monitoring and effectiveness evaluation.

- This could include the development of a global monitoring plan and an effectiveness evaluation process overseen by regional coordination groups appointed by governments and supported by an open-ended scientific group

- The SPP could have a supporting role in the context of its possible role in developing global assessments this could include an independent assessment of the progress and effectiveness of the plastics instrument.

Cross-cutting Functions

Conclusions and Next Steps

Ana Paula DE SOUZA | Human Rights Officer, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

- Plastic pollution – and pollution more broadly – are responsible for ongoing, massive human rights harms that negatively affect multiple aspects of human life.

- Thanks to the best available science, we now know, for instance, that plastics are accumulating in food chains, contaminating water, soil, and air, and releasing hazardous substances into the environment. We also know that microplastics are being found in human blood, lungs, and placenta, as well as in livestock feed and milk and meat products. And that exposure to toxic chemicals often found in plastics is impacting fertility, shortening gestation periods, and lowering birth weights.

- Science is showing us that the plastics cycle has become a threat to all human rights, including the rights to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment, life, health, food, water and sanitation, and equality and non-discrimination. And in doing so, science can give the tools for policymakers to make informed rights-based decisions.

- Reality is not a bed of roses. Heavy corporate influence on regulatory processes, direct attacks on scientific studies, smear campaigns against scientists themselves, and the denial of science have been propelling us ever deeper into environmental catastrophe. Big industries – including those directly benefiting from plastics pollution – have worked to suffocate scientific evidence at the expense of people and the planet.

- That is the very reason why the right to science needs to be protected. For science to flourish and develop, the principles of integrity, transparency, and participation are essential to make science objective and reliable, and to ensure that it is not subject to interests that are not scientific or are inconsistent with fundamental human rights principles and the welfare of society.

- How can this be translated into practice? A human rights-based approach to addressing pollution calls for a vision that aligns with scientific evidence, centers on principles of accountability and informed participation and gives special attention to the needs of people in vulnerable situations. It also requires actions to be guided by key principles including precaution, prevention, intergenerational equity, and non-discrimination.

This requires,

- That an effective science-policy interface mechanism engages all relevant stakeholders and disciplines, securing opportunities for informed participation. The citizen science model of engagement, which ties scientific inquiry to the needs of communities, can contribute to the relevance and impact of the scientific research, ensuring that the benefits of science reach the very people who need their application. Knowledge empowers the communities to exercise agency on their own behalf.

- Information concerning the risks and benefits of science and technology should be accessible without discrimination. The new science policy mechanisms must put in place all necessary efforts to overcome persistent inequalities in scientific advancement through culturally and gender-appropriate means of education and communication, to encourage the widest participation in scientific progress of those populations that have traditionally been excluded from such progress.

- Special attention should be paid to groups that have experienced systemic discrimination in the enjoyment of the right to participate in and to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications, such as women, persons with disabilities, Indigenous Peoples, frontline communities, and persons living in poverty.

- As a precondition, there should be an enabling environment for the conduct of scientific inquiry free, with specific guidelines to ensure the protection of scientists engaging with the respective mandates.

- Drawing from the study, the new science-policy mechanisms to deal with plastic pollution, within the new treaty on plastics, and pollution more broadly within the SPP, must include safeguards to avoid the risks associated with the existence of conflicts of interest by creating an environment in which actual or perceived conflicts of interest are adequately disclosed and regulated, especially those involving scientific researchers who give policy advice to policymakers and other public officials. Guidelines should also be in place to safeguard against attempts by business entities to achieve policy change by influencing research and knowledge production.

- For all this to happen, it is crucial that the mandate of the new Science Policy interfaces explicitly refer to human rights, including the rights to health, to healthy environment and the right to everyone to enjoy the benefits of science.

- Systemic change is necessary to stop the flow of plastic waste into the environment. The path requires, amongst other actions, a reorientation of the purpose of business in society, changing irresponsible business models, while ensuring transparency throughout the lifecycle of plastics and accountability and remedy for harms caused. For this to happen, we must protect the science, to ensure that everyone can enjoy its benefits.

Sam ADU-KUMI | Executive Director, EnviroHealth Consult (EHC) and National Expert, Chemicals and Waste, Ghana

- Many of the existing initiatives globally seek to improve the use of scientific and other knowledge forms in policy decisions, such as IPCC or IPBES, face a number of challenges related to effective communication; mobilization of diverse knowledge forms; and acting upon research findings.

- These are mainly due to the fact that SPIs are conceptualized as linear processes, where science is assumed to provide clear relevant credible, legitimate and actionable knowledge on which decision-makers will pursue decisions. When SPIs are managed as collaborative non-linear processes, scientists, decision-makers and the general public are engaged in an alternative process and negotiate together what information is needed and what kind of evidence is relevant in the given situation.

- The non-linear approach to SPIs can be considered as a way forward toward improved implementation and behavioral change as it also creates space for debate over conflicting beliefs;values and interest.

- The management of the diverse information under the SPI as defined in the report is encouraging because if the SPI on plastics are managed in a collaborative and a non-linear approach, scientists, decision makers and the general public from Africa or developing countries will be encouraged to engage in an alterative process and negotiate together necessary information and evidence.

- The type of necessary knowledge should also include indigenous or traditional knowledge, which is critical for Africa and other developing countries.

- Effective communication and outreach, as underlined by the report, are an important part of the cross-cutting functions. These will help both internal and external communication. There’s a need to establish a knowledge-management mechanism and data hubs, particularly in developing countries such as African ones.

- Acting upon research findings. In developing countries we need the generation of data or conducting the research which could be followed by the action on the findings. We call for the establishment of a dedicated reliable and sustainable funding mechanism that will help build capacities in developing countries. This also facilitates the involvement of developing countries such as Africa in the entire process.

- One of the recommended actions in the report is the development of policy support tools such as technical guidelines, best available technologies and techniques, and best environmental practices on toolkits which will help in the policy formulation for Africa.

Christos SYMEONIDES | Clinical and Research Specialist, Minderoo Foundation

- The global community is standing at a crossroads with respect to managing our relationship with plastics. There’s an urgent need to strengthen the SPI. If this is to lead to meaningful change that takes us down a different path, it is science that has brought us to the realization that our current relationship with plastics is not sustainable.

- The science of environmental and human health impacts of plastics throughout the production, use, and disposal phases of plastics indicates that these are major externalities of plastics that are not currently incorporated into this economics and urgently need to be addressed in the face of plastic production that’s already unsustainable and continues to rapidly escalate. It science that offers a safer path forward through the science of biomonitoring and human health surveillance, the science of green chemistry and alternatives and the multi-disciplinary; science of transition and system change.

- If the global community embeds a science-informed approach at the center of this treaty, it sets itself off to avoid repeating the mistakes that led to the current situation and addressing these problems with health. An effective and comprehensive science-policy interface to address plastics is necessary and the report is a road map for how to put in place an effective instrument.

- The 10 key functions explored and researched by the report and their comparison with already existing relevant capacities and what is in the scope of the science-policy panel, what additional gaps would need filling to meet the goals of the plastic treaty and, critically how the three could work together.

- The SPI for plastic pollution can answer interdisciplinary concerns such as human health by including those essential functions not captured within the mandate of other SPIs. An effective SPI able to address interdisciplinary issues such as human health is achievable. This report demonstrates that the science-policy interface needed for an effective treaty can be mapped out into discrete individual functions and broken down this way, the complex becomes clear.

- We can make provisions for the full breadth of independent, interdisciplinary scientific input needed. We can explore where their functions and capacities may already be present and where there’s an opportunity for synergies and cooperation. When gaps in capacity are identified, examples of similar functions within existing multilateral environmental agreements can be drawn upon.

- This report is a reason for optimism of this critical crossroads in the global treaty. Through it, member states and observers will meet at the third session of the intergovernmental negotiating committee on plastic pollution (INC3) with a road map to build an effective science-policy landscape to support the treaty. This can then support an effective plastic treaty that can lead to meaningful change in our unsustainable relationship with plastics including its impacts on human health.

Amila ABEYNAYAKA | Policy Researcher, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES), Japan | Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty

- The Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastic Treaty is an international network of diverse independent scientific and technical experts that seeks to contribute with summaries and interpretations of scientific knowledge to decision-makers and other stakeholders involved in the negotiations.

- Building on the work of the number of groups, we recommended proceeding with the development of safety, sustainability and transparency assessment criteria for chemicals polymers, products, technologies and systems along the entire life cycle of plastics, including alternatives and substitutes.

- This criterion would guide decision-making on core obligations and control measures. These dimensions are mutually supportive and reinforce the mission of closing a significant governance gap. They should be guided by independent expertise and scientific consensus and the principles of the latest version of zero hierarchy prevention and precaution.

- The SPI of the treaty itself should meet four key requirements: credibility; legitimacy; salience; and agility. These requirements can be best realized through the establishment of a dedicated scientific body under the future instrument.

- The SPI may develop a hybrid regulatory classification system based on the pre-existing assessment criteria by the BRS and then it could consist of lists of prohibited; restricted; permitted and exempt, which could be amended with the future treaty.

Key Principles for an Effective Science-Policy Interface

Jacob KEAN-HAMMERSON | Ocean Campaigner, Environmental Investigation Agency

- Having an effective institutional structure, including an efficient and regular interface between science and policy, is really essential to a well-functioning treaty.

- Essential aspects of the science-policy interface and the bodies that should be established under the

instrument to facilitate this include three essential areas of assessment. The scientific assessment, the technical assessment, the socioeconomic assessment of the instrument and its implementation. While these are distinct functions, they could be organized following the model of the Montreal Protocol for example. - We could use the report to look at organizing these bodies into the day-to-day functioning of the new treaty and this iterative process of policy-making that we want to undergo in the new instrument and the undertaking to end plastic pollution. These include the kind of really critical responsibilities including horizon-scanning for future issues; reviewing the reporting and monitoring data provided by the parties; providing assessment of substitutes and alternatives; success of control measures and of the treaty as a whole; including the financial needs of parties and the replenishment of any funds that will be established to support the instrument.

- It is important to set a firm and stable foundation from the outset and that comes with this clear institutional structure. There is a key difference between including within the text of the instrument a provision that allows the governing body to establish these bodies at some time rather than establishing them directly within the text of the agreement as standing bodies. We encourage negotiators to consider doing this because this gives the bodies particular prominence for the importance of their role and is able to outline the key functions that would be expected of them.

- As it relates to the science-policy interface functions and its relation to the science policy panel that is currently being negotiated, EIA believes is essential to keep all the necessary functions of the SPI within the architecture of the agreement so it’s able to function holistically on its own. The science-policy interface under the instrument will need to be able to answer specific policy questions for example on thresholds for impacts on biodiversity and the functioning of ecosystems as it relates to the impacts of plastic pollution and scanning of emerging issues that should be addressed.

- It is really important not to lose these functions from within the architecture of the instrument as these bodies will exist to speak specifically to the governing body and provide advice in the policymaking process across the full life cycle of plastics. Not having such functions could limit its ability to play a key role from the outset.

- EIA is part of Break Free from Plastic, a global movement of more than 2,700 organizations and a thousand individuals who envision a world free from plastic. Among its priorities is the establishment of an SPI that should take the form of a subsidiary body and which displays a robust conflict of interest policy and its strict implementation. To ensure the integrity of the body, Break Free From Plastic also highlights the need for the science-policy interface to be inclusive and reflect regional, gender, disciplinary, sectoral, and multi-stakeholder representation that includes impacted communities and indigenous peoples.

- The science-policy interface must be agile within review and scientific flexibility.

Q&A

Q: How can industry stakeholders be involved in this effort moving forward? What role is the industry going to have:

Niko URHO: The report touches upon the issue but technical expertise from the industry is needed. An example is provided by the Montreal Protocol’s Technology and Economic Assessment Panel (TEAP), organized into six technical options committees known as talks for industrial sectors they have experts from the industry, government, and academics and these are nominated by parties and selected primarily based on the technical expertise. While including members from the industry based on their technical expertise, developing a robust conflict of interest policy with clear guidelines on how to manage conflict of interest; and disclosing any information on financial and other interests is important to emphasize objectivity and integrity that are guiding principles of many existing SPIs.

Amila ABEYNAYAKA: The industry plays an important role because of the complexity of plastics and chemicals information. The industry if fundamental in providing data, making interactions, and inclusion of such inputs key.

Q: Could single-use plastics be classified as hazardous waste and why?

Karen RAUBENHEIMER: The term ‘hazardous’ is very specific. Through the report, we often used ‘of concern’ instead, and it might be more appropriate in this case as it does not require the technical proofs to establish the scientificity of whether it is hazardous. Lumping all single-use plastics under that might be problematic.

Christos SYMEONIDES: It is important to bring in the health angle. When we talk about something being hazardous, we refer to various aspects: hazards to the environment; hazards to human health or hazards that relate to intrinsic risks of exposure. Phenomena like bioaccumulation or long-distance transport that we see in the definition of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs).

The importance of having a robust SPI is also stark for the need to define the term ‘hazardous’ and its properties. From a human health perspective, we are keen to see a broad consideration of hazards related to plastics that include endocrine disruptors. We should be looking at this optimistically in understanding what the next generation of plastics or alternative materials can avoid the hazards in current plastics.

Q: How can we ensure that the future plastic treaty has a strong sign scientific body that not only is policy-relevant but also is also avoids being policy-prescriptive?

Walter SCHULDT: The key will be to ensure the specificity for each of the functions. During the first two sessions of the Open-Ended Working Group for the SPP on chemicals, waste and pollution prevention and of the plastics INC, a clear majority of states and other stakeholders advocated for that function to be fulfilled. At the same time there is a need for openness and complementarity. As the report showed, the role of the SPP could tackle various focus areas and one of those could be on plastic pollution. In the different submissions and the different discussions in the first two INC sessions, there have been voices advocating for a very focused specific role of relevant science-based information including for instance future listing or future determination of hazards. What will be the future of that relevance without being prescriptive will be determined?

Q: Why we do not stop identifying and managing the conflict of interest and not aim to prevent and eliminate it?

Amila ABEYNAYAKA: Everybody has some kind of interest based on their working place or funding, thus it may be better to prepare guidelines and identify the cases in which a potential conflict of interest can arise and manage it accordingly.

Video

Documents

Links

- Science-Policy Interface for Plastic Pollution Full Report | GRID-Arendal

- Science needs to be the foundation of the new Plastics Treaty | GRID-Arendal Press Release | 7 November 2023

- Plastics and the Environment

- Towards Plastic Pollution INC-3