Event Virtual

Implementing a Treaty to End Plastic Pollution: A Holistic Approach to Resource Mobilization & Financing for Systems Change & Just Transitions

07 Feb 2024

15:30–17:00

Venue: Online | Webex

Organization: Forum on Trade, Environment & the SDGs, Geneva Environment Network

Organized by the Forum on Trade, Environment & the SDGs (TESS) and the Geneva Environment Network, with the support of the Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues, this session provided governments and stakeholders with a holistic overview of options and pathways for mobilizing resources for effective treaty implementation, systems change, and the just transitions required to end plastic pollution.

About this Session

Implementation of obligations arising from an international legally binding instrument to end plastic pollution will require large-scale mobilization of both public and private resources and finance.

In the intersessional period ahead of the fourth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution (INC-4) that will take place from 23 to 29 April 2024 in Ottawa, Canada, an improved understanding of the scope of resource mobilization and financing needs, the range of their potential sources, and options for financial mechanisms and related decision-making methods will support governments and stakeholders to advance negotiations and secure an ambitious outcome.

This session provided governments and stakeholders a holistic overview of options and pathways for mobilizing resources and financing for effective treaty implementation, systems change, and the just transitions required to end plastic pollution.

Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues

The world is facing a plastic crisis, the status quo is not an option. Plastic pollution is a serious issue of global concern which requires an urgent and international response involving all relevant actors at different levels. Many initiatives, projects and governance responses and options have been developed to tackle this major environmental problem, but we are still unable to cope with the amount of plastic we generate. In addition, there is a lack of coordination which can better lead to a more effective and efficient response.

Various actors in Geneva are engaged in rethinking the way we manufacture, use, trade and manage plastics. The Geneva Beat Plastic Pollution Dialogues aim at outreaching and creating synergies among these actors, highlighting efforts made by intergovernmental organizations, governments, businesses, the scientific community, civil society and individuals in the hope of informing and creating synergies and coordinated actions. The dialogues highlight what the different stakeholders in Geneva and beyond have achieved at all levels, present the latest research and governance options.

Following the landmark resolution adopted at UNEA-5 to end plastic pollution and building on the outcomes of the first two series, the third series of dialogues will encourage increased engagement of the Geneva community with future negotiations on the matter.

Speakers

By order of intervention.

Mahesh SUGATHAN

Senior Policy Advisor, Forum on Trade, Environment & the SDGs (TESS)

Elena CIMA

Lecturer, International Environmental Law, University of Geneva

Tim GRABIEL

Senior Lawyer & Policy Advisor, Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA)

Ambrogio MISEROCCHI

Policy Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation

Soumyajit KAR

Lead, Sustainable Trade, World Economic Forum

Dominic CHARLES

Deputy Director, Plastics, Minderoo Foundation

Peggy LEFORT

Pollution and Circular Economy Lead, UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI)

Gizem LANGE

ProCredit Group | Finance Leadership Group on Plastics

Diana BARROWCLOUGH

Senior Economist, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

Carolyn DEERE BIRKBECK

Executive Director, Forum on Trade, Environment & SDGs (TESS) | Moderator

Highlights

Video

Livestream on Webex

Summary

Welcome

Carolyn DEERE BIRKBECK | Executive Director, Forum on Trade, Environment & SDGs (TESS) | Moderator

- Ending plastic pollution will require system changes across the life cycle of plastics as well as just and fair transitions.

- The Plastic Pollution Treaty must catalyze the necessary system change to support those just transitions and ensure adequate means of implementation. It will need specific provisions to spur and support the resource mobilization needed.

- There is a strong recognition of the need to mobilize resources from a range of different sources in all countries and especially for developing countries.

- Necessary means of implementation include financing and in addition technology transfer and capacity building.

- Implementing the treaty will require large-scale mobilization of public and private resources and financing. This webinar aims to inform government and stakeholders on the scope of resource mobilization and financing needs, the range of potential sources, and the options for financial mechanisms and decision-making.

- There will be a need for a holistic approach to mobilize resources and leverage already available ones and align financing that is available with the goals of the treaty.

I. Mobilizing Resources and Financing for Treaty Implementation

Scope of resource mobilization and financing needs for treaty implementation across the life cycle of plastics | Mahesh SUGATHAN | Senior Policy Advisor, Forum on Trade, Environment & the SDGs (TESS)

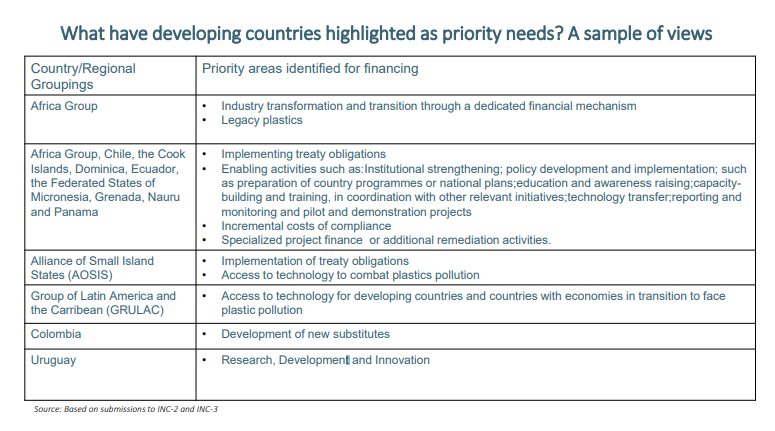

- There will be diverse resource needs that arise in the implementation of the plastics treaty one of which is financing which is the focus of this presentation. Developing countries have highlighted some priorities in their submissions to the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee.

- Two recent reports have estimated the cost implication of ambitious actions to address plastic pollution:

- The Nordic Council of Ministers’ Report Towards Ending Plastic Pollution By 2040 estimates that, in a scenario where global rules are adopted to implement 15 far-reaching policy interventions across the plastics life cycle, cumulated public expenditure from 2025 to 2040 would amount to about USD 1.5 trillion, while a further USD 15.4 trillion would be needed from the private sector.

- In their analysis, governments would cover the cost of expanding collection, sorting and disposal infrastructure while the private sector would cover investment in the production of virgin plastics and alternative materials, recycling infrastructure and the expansion of new business models. This is less than the funding required in the business-as-usual scenario, which would require high levels of investments in continued plastics production and waste management to address increases in plastic pollution.

- The Nordic Council of Ministers’ Report Towards Ending Plastic Pollution By 2040 estimates that, in a scenario where global rules are adopted to implement 15 far-reaching policy interventions across the plastics life cycle, cumulated public expenditure from 2025 to 2040 would amount to about USD 1.5 trillion, while a further USD 15.4 trillion would be needed from the private sector.

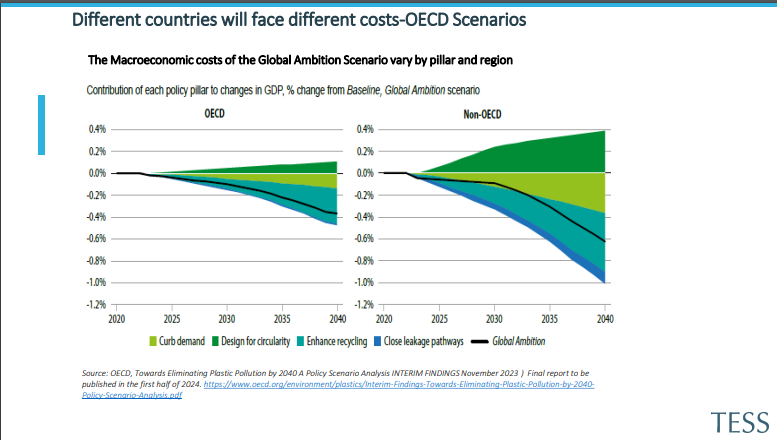

- Notably, both the Nordic Council and The Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development’s (OECD) Global Ambition Policy Scenario found that the cost and resource implications, will vary between developed and developing countries.

- OECD modeling shows that non-OECD countries will have greater needs across all activities identified for reducing plastic pollution. Overall, the costs are substantially higher in non-OECD countries amounting to 0.62% GDP loss from baseline in 2040 than in the OECD countries where costs amount to 0.37% loss from baseline GDP. The largest costs as a share of GDP of global ambitious action are projected for fast-growing countries with less advanced management systems, such as sub-Saharan Africa. For example, investment needs for waste collection sorting and treatment amount to more than USD 1 trillion between 2020 and 2040 for non-OECD countries combined.

- The implementation of an ambitious treaty will require an investment of resources domestically by both developing as well as developed countries

Diversity of Financing for Diverse Objectives

-

- A range of means of implementation will be required including financing, technology, capacity and capacity building.

- Focusing on financing, funds will be need for:

- costs associated with the core activities of the Secretariat and running the conference and Parties;

- administrative and institutional costs at the domestic level related to treaty implementation.

- This could include costs related to monitoring, and reporting obligations under the treaty as well as costs of implementing specific treaty-related provisions, such as new regulations to meet product design requirements, or related to commitments to eliminate or restrict problematic plastics, implementation of waste management provisions, and cleaning up of legacy waste.

- costs for enabling and supporting the systemic changes within countries to implement a treaty.

- The ability of many businesses to advance changes in production business models or products will rely on regulatory incentives and on access to finance, technologies and capacity building. In some instances, there are likely to be costs associated with transitioning away from certain products and production methods, which will also require attention to financing to ensure just transition. Activities beyond those explicated in the treaty may be supporting clean water infrastructure to reduce the need for plastic bottles.

- Adequate financing will potentially enable effective national action to address pollution along the plastics value chain. As various country submissions to the INC from both developing and developed countries make clear, public finance and Official Development Assistance (ODA) alone will be vital but insufficient to address the scale of the plastics pollution challenge and the range of needs across the life cycle.

- Treaty provisions can play a role in providing regulatory certainty and the environment to guide and catalyze private sector investment.

Developing Countries Priority Needs

- Developing countries face higher fiscal constraints and more limited access to private sector financing and technology on fair terms.

- Discussions at the INC have provided examples of some of these financing needs at every stage of the life cycle. These include legacy plastics and remediation, improving waste management, capacity support for meeting product design requirements, support for switching to non-plastic substitutes and support associated with a phase-out of chemicals and products.

- The challenge is to develop a clear understanding of what kinds of financing and resources are needed for addressing each of these needs, where we can source that financing or technology more suitable for addressing those needs, how we can ensure that resources flow towards the key priority areas including the largest systemic needs and what kind of international mechanisms partnerships and initiatives can be catalyzed by the treaty.

- We must not forget legacy plastic pollution and the imperative to raise resources to clean up existing legacy plastic pollution as well globally.

Experiences with existing MEAs: A Diversity of Approaches and Mechanisms Harnessing Domestic and International Resources | Elena CIMA | Lecturer, International Environmental Law, University of Geneva

Existing Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs) and treaty regimes deal with resource mobilization and financing in many ways. Existing mechanisms offer many lessons to learn in terms of approaches and best practices.

- Resource mobilization is the specific component of an MEA that deals with facilitating the implementation of the treaty, compliance with it and achievement of its objectives. Means of implementation refers to finance technology transfer and capacity-building. These are interconnected elements as exemplified by different MEAs where financial mechanisms serve the specific purpose of providing financial support for technology transfer, capacity building, technical assistant training.

- There are different types of resource mobilization provisions deployed in MEAs. The combination of types varies based on the sizes of the MEA framework.

- There is a lot of variety in terms of how different MEAs decide to deal with resource mobilization. It is up to the parties of each MEA to decide what of these types of provisions are needed.

Financing mechanisms can be differentiated based on their purpose, source and structure.

- Purpose | Some are simply just aimed at covering the administrative costs of secretariats, the COP, commissions, bodies of the MEA, while most financing mechanisms aim to facilitate developing countries’ efforts to comply and implement the MEA.

- There are combined ones, for example, the Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species (CITES) has both a fund that deals with administrative costs but also an external trust fund that deals with facilitating developing countries’ compliance with MEAs. Within the funding category devoted to facilitating developing countries, there are different ways to achieve such purposes. Also, they can have some financing mechanisms that deal with emergency assistance and compensation in case of loss or damage.

- Source | While some MEAs focus on public finance – either relying on voluntary or mandatory contributions or combinations of the two like in the case of the multilateral fund of the Montreal protocol, applying the common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR) principle – it is possible to have combination of contributions from member states, public and private funds.

- A relevant example of mixed funding is the adaptation fund of the Kyoto Protocol, which combined voluntary contributions from member states with a levy of 2% of the certified emission reductions issued for each Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) activity.

- MEAs can also create mechanisms that mix these different sources: there is not a one-size-fits-all approach or a silver bullet.

- Structure | MEAs have either established their own standalone mechanisms, rely on what is already there such as the GEF, or employ hybrid mechanisms.

Key Messages

- There are many examples of different mechanisms that already exist.

- A range of resource mobilization provisions can be used depending on the needs.

- MEAs often follows more than one approach in terms of purpose, source, and structure.

For example, the climate change regime encompasses several MEAs adopting different approaches:

- In terms of financing mechanisms, there are different funds for different purposes (e.g. the loss and damage fund for loss and damage, theGreen Climate Fund finances mitigation and adaptation projects)

- Some funds rely on public, public and private, and on public plus levy, combining all those mechanisms. Some rely on existing facilities like the GEF for the adaptation fund and then specific funds that have been created.

A one-size-fits-all does not work. The different elements characterizing different treaties can be harnessed in different ways and combined depending on needs.

Options for financial mechanisms, including options related to multilateral funds, hybrid approaches, coordination and decision-making on resource allocation | Tim GRABIEL | Senior Lawyer & Policy Advisor, Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA)

- To end plastic pollution or at least to approximate that objective, this treaty will require a robust financial framework.

- Despite often being depicted in discussions as a question of either having a newly established multilateral fund or relying on the Global Environmental Facility (GEF), what we need is an all-of-the-above approach given the nature and magnitude of the problem.

- It is important to talk about the types of activities and costs that require financial support to understand which mechanisms are best positioned to deliver that financial support. We need to find funding for:

- Enabling activities in developing countries that allow implementation and compliance. These include institutional strengthening for governments overseeing international and national implementation and cover reporting and monitoring as well as policy development and implementation.

Enabling activities should be provided universally to all the eligible countries to ensure a baseline of support governments can rely upon to fulfill the core obligations that will make the treaty work. This includes compliance overseeing mechanisms, reporting and monitoring, and policy and development implementation.

- Clearing house functions like capacity building and training of focal points and industrial actors; education and awareness raising; information exchange and regional cooperation coordination.

The delivery of these clearing house functions should be a priority. For instance, the Montreal Protocol delivers these functions via its compliance assistance program (CAP), which oversees a series of regional networks that gather focal points annually. These feature information capacity-building, training sessions, education and awareness raising, experience exchanges between new and old ozone officers. These networks are overseen by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and have proven to be very successful in supporting implementation as one of the main factors that contribute to the Montreal Protocol being considered the most successful environmental agreement in the world. - Agreed incremental costs – these are additional expenses related to compliance. Their definition is linked to the obligations that will be agreed in the treaty.

- These 3 categories of activities (enabling activities, clearing house functions and agreed incremental costs) can only properly be delivered via a newly established multilateral fund, as demanded by many developing countries.

- The Global Environment Facility (GEF) was never designed to deliver this type of financing with the regularity, consistency and predictability required in this context.

- There is a fourth category of activities: concessional finance for specific projects across the value chain. For example, projects related to waste management, infrastructure, or remediation. This concessional finance could be provided to governments and the private sector to unlock their investment.

- GEF is very well positioned to deliver project-based concessional financing to the governments. We should carve out a role for and create a window for GEF to access these funds.

- Mechanisms should be created to allow multilateral development banks (MDBs), regional development banks and international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the World Bank or the Asia Development Bank to help enlist them and unlock private sector finance through preferential loans or blended finance opportunities. MDBs and IFIs could also help create windows of opportunities to get some of the private sector investment by providing some favorable terms through concessional finance.

- We must be innovative in the financing mechanisms as there is no precedent for having a systematic way of doing so at the amount and scale of finance needed.

- We need an all-hands-on-deck approach towards providing financial support. It needs to start with the newly established dedicated multilateral fund with well-designed windows of opportunities to GEF, MDBs and IFIs, which can be referred to as the Plastics MLF+.

II. Implementing the Polluter Pay Principle

Extended Producer Responsibility | Ambrogio MISEROCCHI | Policy Manager, Ellen MacArthur Foundation

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) is one of the mechanisms that can support the treaty implementation and a fee based on EPR is an important piece of the puzzle of financing the necessary system change.

- A fee-based EPR is one among other instruments to implement the polluter pays principle. Such a scheme is a performance-based regulation where outcomes, objectives, roles, and responsibilities of all involved stakeholders are set and defined by law.

- In the fee-based model, EPR requires companies who introduce products or packaging to be responsible for these and participate in their management. Companies must also provide funding dedicated to the to use, collection and processing, and management of those products.

- A similar example we often hear about is the deposit refund systems (DRS), which can work alongside or integrated into fee-based mandatory EPR policies. The revenues generated by these schemes are based on the underlying principle of the net cost.

- It is important to talk about EPR as it is a proven mechanism to reduce waste disposal and increase collection for recycling rate and in some cases, recycling in practice.

- The chart presents an analysis in 2021 aiming to compare countries with no EPR to countries with limited or voluntary EPR and countries with mandatory schemes. The chart refers to the collection for recycling rate.

- Countries with mandatory schemes perform on average much better than the other countries. The concept of EPR is applied across different sectors, among which plastic packaging, relevant in the context of the treaty.

- Extensive literature exists on the positive effects of EPR schemes in sectors including electronic waste, batteries, vehicles, tires, and others. In the past years, there has been growing evidence that EPR can have a positive impact on sectors including textiles other plastic products and construction materials.

Key messages

- EPR is a proven mechanism to reduce waste disposal and increase recycling.

- Beyond improving waste management performances, EPR has proven to be able to generate funding as a mechanism and alleviate pressure on the public budget as well as pressure on taxpayers.

- The amount of money that can be generated through EPR schemes as domestic resource mobilization can contribute on top of the Official Domestic Assistance (ODA) and international financing.

Examples of EPR schemes as a mechanism to generate funding

- Referring to the chart, estimates performed in 2015 in Europe quantified the impact of fee based EPR to around 3 billion EUR per year. A more recent assessment based on the 2022 data and including DRS schemes and taxation in some EU member states found that revenues could be up to 7 billion EUR or USD 7.5 billion a year in Europe alone.

- In France, assessments based on 2021 reported data show that revenue was around $900 million per year.

- In South Africa, revenues from EPR schemes were estimated at 2.5 billion Rands or $130 million over five years.

EPR’s Role in financing the implementation of Plastics Treaty

- Estimates found that USD 1.5 trillion will have to be provided over the period 2025 – 2040. This amount of money represents the non-private direct investment. The 15.4 in the global rule scenario are direct investments from the private sector, while the 1.5 represents the money that is required beyond those direct investments of the private sector.

- EPR can play a critical role in providing private sector funding and removing pressure on the public budget at the national domestic level. By enforcing and establishing EPR legislation, it is possible to provide clarity to the market that in turn will be able to attract public and private investments to cover the capex – the capital cost where infrastructure is lacking.

- EPR legislation can bring a twofold beneficial impact by:

- providing a significant amount of funding for running the implementation of the treaty obligations and cover this part of the public budget that is required and

- create trust and confidence in the market through harmonization and clarity on where investment are actually needed.

EPR | Lessons Learned from Developing Country Experiences and Challenges | Soumyajit KAR | Lead, Sustainable Trade, World Economic Forum

Various countries are in the process of or already implement some forms of mandatory EPR for packaging.

- In the discussions leading up to the potential implementation of the plastic treaty, EPR have been gaining a lot of ground including in developing countries.

- EPR has proven to be a useful tool in the circular economy, but it is also important to inspect some of the sticky challenges that are peculiar to developing countries.

Learnings from EPRs in Developing Countries

- In the case of trust deficit, it has been the case often that when governments propose some sort of a plastic tax or pollution tax, they are not implemented with transparency in how that fee has been earmarked. If producers are paying into a pot or tax that is supposed to work towards a circular economy but it flows into the general government budget then there is not much incentive among the private sector to be true stakeholders in an EPR scheme.

- In terms of quality and sophistication of waste management, EPR is a really good source of running or operating expenses for a circular economy in any country but it needs to be complemented with capital expenditure that will then help set up the infrastructure in waste management that can actually lead to proper performance of the scheme. Without a well-functioning waste management system, EPR is less likely to succeed.

- The definition of key performance indicators (KPIs) is essential to functioning EPR schemes. Undue focus on collection will lead to little control over what happens to waste after it is collected. While designing a good EPR system one needs to really look at KPIs not just in the collection but also on what happens to the collected waste.

- A well-designed EPR system provides a good opportunity to formalize this sector and make them meaningful stakeholders in a well-functioning EPR system.

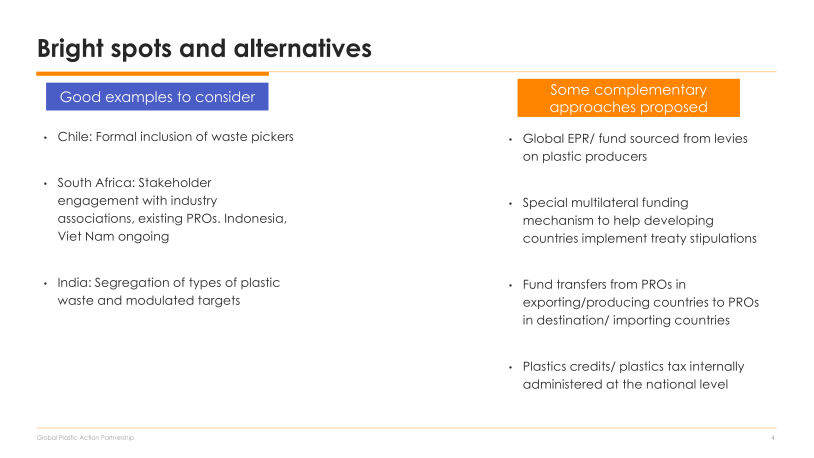

While EPR is not the silver bullet for circular economy or implementation of the global plastic treaty in the global South, it proves to be a useful mechanism and needs to be looked at with complementary approaches, including:

- A global fund that levies on plastic producers could look at setting up some of the critical infrastructure.

- Multilateral funding mechanisms, which can be mixed with ODA, to help developing countries in implementing the treaty.

- Finding ways to ensure that exporting country responsibility organizations pay their fair share to countries that are actually dealing with the waste or importing countries.

- Plastic credits or plastic taxes.

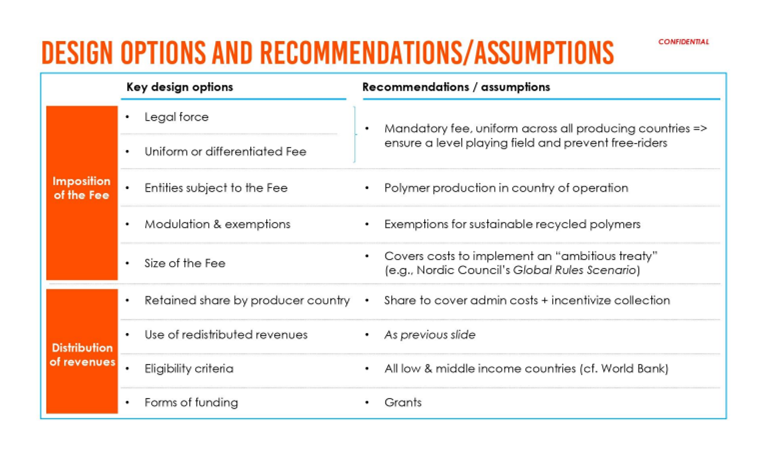

Fee on primary plastic production | Dominic CHARLES | Deputy Director, Plastics, Minderoo Foundation

- A fee on primary plastic production can be a critical complement to the other sources of funding both public and private.

- Minderoo will publish a study looking at the potential impacts that a plastic pollution fee could have across environmental, social and economic needs around six weeks before INC-4.

- The envisaged fee could support developing countries in covering and meeting the significant and unique costs of treaty and implementation that can end plastic pollution. Significant and unique costs could be:

- Development of safe and environmentally sound waste management infrastructure. This refers to the capital expenditure required to meet formal collection, sorting, recycling and disposal needs. EPR can represent a great source of funding for the operating expenses of dealing with plastic waste getting EPR schemes off the ground is complex. Therefore, a fee on primary polymers could raise the funds to build the capex – the capital infrastructure to get those systems up and running.

- Transition to a sustainable circular economy and the infrastructure required. This requires generating the capital expenditure required to scale, reuse and substitution model, stimuli around design for recycling or the elimination of single-use plastics. Regulation alone is unlikely to be enough. Significant investment from the public sector will be needed to get these fundamental shifts in the plastics economy up and running. The plastics fee could provide that capital investment.

- Ensuring a just transition. Waste workers across the globe are not achieving a living wage through collecting and selling plastic waste. They are about 50% below what they require for a living wage. A plastic pollution fee could support that just transition.

- Addressing legacy plastic waste. The cost of remediating plastic legacy waste in unsanitary landfills, beaches, in the ocean are extremely high and will require an additional source of funding beyond what the public or private sector might be able to invest.

- Across these four potential uses we expect a total sum of USD 30 to 40 billion per year in developing countries, after additional financing is collected from EPR for instance. This magnitude of investment is not going to be met realistically by ODA.

Fee Design Options and Recommendations

- Expected Environmental Impacts – early analysis show that without a fee, an ambitious treaty will fall short of ending plastic pollution.

- In the example of mismanaged plastic waste, scenarios offer different outlooks of the plastic pollution situation:

-

- In a business-as-usual scenario, a doubling of mismanaged plastic waste is forecasted to take place in the next 15 years.

- In the “Global Rules Scenario” developed by the Nordic Council that does not entail any fee on primary plastic polymer, there would be a significant reduction amounting to about 50% of mismanaged plastic waste, but with a significant amount of mismanaged waste still leaking into the environment.

- closing that gap and fully funding those costs to deal with mismanaged plastic waste through a fee on primary plastic production would potentially reduce mismanaged waste to 10% of its current level. The plastic fee, complemented with other control measures and provisions is absolutely essential in tackling mismanaged plastic waste.

Polluters Pay Principles in Comparison

- EPR and Plastic Pollution Fee are two mutually reinforcing mechanisms that can provide complementary sources of finance.

III. Private Finance Partnerships and Resources

Aligning private finance and investment with treaty goals: banks, insurers, investors | Peggy LEFORT | Pollution and Circular Economy Lead, UN Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI)

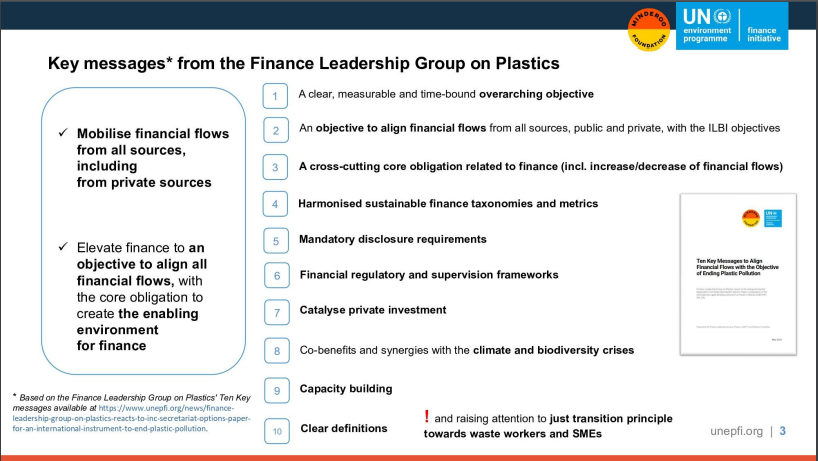

- The Finance Leadership Group on Plastics, a UNEP-FI-led core group of banks and insurers from all regions with total assets close to $10 trillion, aims to contribute to the development of the future instrument to end plastic pollution from a private finance perspective; and to build awareness and readiness in the finance sector to respond to the future instrument through their investment and financing.

- Mobilizing financial resources will be key to the success of the future instruments. This means mobilizing public financial resources but also private financial resources. Ahead of INC-2, the finance leadership group on plastics formulated ten key messages on how to accelerate and scale up the mobilization of financial flows from all sources including the private sector.

- The future plastics instrument could send a strong signal to member states and finance actors on the imperative to mobilize and re-orient financial resources. This can be done through an objective to align financial flows from all sources, public and private, with the treaty’s objective and targets. This would build on what has been done in Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement and in goal D of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. If the same model is not followed in the plastics instrument, it would signal that plastic is a lower priority than climate and biodiversity.

- The future plastic instruments must create a mandatory framework and environment that will enable the redirecting of financial flows. UNEP-FI and the Minderoo Foundation devoted a paper to the meaning of aligning and redirecting financial flows. It affirms that to end plastic pollution, financial flows from all sources will not only need to be mobilized but also need to be massively redirected. They will need to be reduced in certain areas of the plastics value chain like virgin production and increased in substitute production, new delivery models, collection and recycling. It will be important to set clear targets along the plastics value chain. Finance actors need to know where to increase or decrease their investments and financing along the value chain.

- The future Plastics Agreement has the potential, through instruments such as subsidies, plastic fees, and de-risking mechanisms, to incentivize certain investments that need to increase and disincentivize others that need to decrease.

- In the perspective of INC-4 it will be very important to better understand the overall plastics finance landscape and the respective role of public and private finance and to understand that the public sector has a key role to play in catalyzing private finance.

Gizem LANGE | ProCredit Group | Finance Leadership Group on Plastics

- To enable systemic change, all actors, public and private including financial institutions need to play their roles, which are complementary to each other.

- Without mobilizing private finance, we cannot end plastic pollution. Private finance institutions also need to channel private capital into the direction of solutions, divesting from problematic investments. Those investments in this direction are often too risky for private institutions with very little or sometimes no return in the absence of the right regulatory framework. Downstream solutions are seen as expenses rather than value-creating high-return investments.

- Financial institutions also face challenges in getting data to assess the risks and look for opportunities to invest because there are no disclosure requirements. To manually collect the data from the customers is very costly.

- This produced challenges in the implementation of the plastic strategy in the ProCredit group. ProCredit group is a group of impact-oriented Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) banks operating mainly in Eastern and Southeastern Europe. In 2019 ProCredit developed its plastic strategy to increase the sustainability of the clients engaged in plastic production. The implementation of the strategy was challenged by the lack of tangible returns that clients could pinpoint.

- When financial institutions try to stir positive change without the support of regulatory mechanisms, they need to take risks themselves, which is problematic in terms of scalability.

- Private capital can be leveraged by:

- enhancing the risk-adjusted returns on investments with the right regulatory framework, by de-risking investments and increasing the return from them, and

- close the data gap can by the mandatory and harmonized disclosure requirements for companies. This would in turn increase transparency, put all the financial institutions on a level playing field and not penalize those who are proactive in mobilizing their financial flows towards solutions.

IV. Public Finance and Resources

Public Finance and Resources | Diana BARROWCLOUGH | Senior Economist, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD)

- The reasons for sealing a plastic treaty and producing a system change to address plastic pollution include addressing the challenges of global warming, climate change and development and consequently achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Therefore, financing for plastic needs to be complementary with financing SDGs and development.

- The production of plastic is increasing massively. 79% of plastic becomes waste and without financial instruments such as EPR plastic waste will continue to rise.

- The decision taken at the Climate Change COP28 to transition away from fossil fuels will inevitably change how we think about plastic as it will impact its price. Changes in plastics prices will automatically lead to the financial changes we aim to produce.

Mobilizing Resources for Ambitious and Just Transition and Transformation

- Global Funds | UNCTAD has for a long time talked about the need for a trade and environment fund. Despite various funds are already exist, these have not been as forthcoming as hoped, making it necessary to look at the whole set of options for finance to produce a system change in the plastics economy.

What Markets Can Do and Are Doing in Terms of Plastic Finance

- Markets are a major source of finance. They are extremely efficient at inventing and producing new forms of plastics. The global trade in plastic is currently worth over a trillion dollars per year. As it is currently impossible to establish the monetary value for the whole global production of plastic, it is mandatory to have proper disclosure to get a handle on how big the value of this sector really is.

- Trade in plastic is enormous and markets are extremely effective at producing and trading plastic. Markets have also been very effective at producing substitutes for plastic, amounting to one-third of the total market in plastics.

- The market-oriented approach would say that Schumpeterian “creative destruction” powers will release a great energy of entrepreneurship and new products that could benefit from the fee-based EPRs as well as markets for other substitutes.

- If we take the example of the SDGs, considering that their realization requires only 1% of global financial assets and yet is still unaccomplished, it is clear that green funds have been disappointing and tend to be short-term, making it essential for the public sector to step in a play a key role.

- If and when major changes in plastic production and trade occur, developing countries will need help adjusting as the export of plastic is a very large proportion of their exports. It is necessary to set up mechanisms that will help them adjust, whether changes are produced by regulations or the treaty itself.

Non-market mechanisms to address plastic pollution:

- Turning off already existing taps that encourage production and consumption of plastic. Since the Paris Agreement, there has been no abatement of fossil fuel finance, which is the best indicator for plastics because of their strong correlation and as statistics on plastics finance are currently unavailable. This shows that an important amount of money is still invested into plastic. Fossil fuel subsidies – implicitly lowering the cost of the inputs into plastic and potentially encouraging more consumption – amount to over a trillion dollars. If these could be redirected and put to other uses, these would also help curb plastic overproduction and waste.

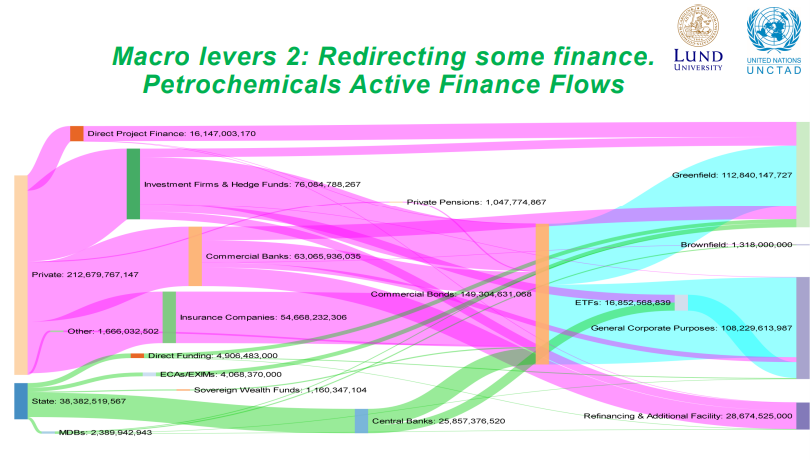

- Redirecting finance. Finance going into petrochemicals represents over 90% of what goes into plastic. The flows indicated in green (see slide below) come from central banks and public development banks and could be redirected and turned into a new source of financing for reducing plastic pollution.

- Scaling up DFIs. Finance in development banks, such as the World Bank, has fallen dramatically over the last decades, while these are the funds that are going to be needed to help capitalize and harness the private sector. Such funds and banks are owned by governments, making it necessary to increase their capitalization and give them the scope to be able to increase their lending in ways that will help support enterprises and countries that are trying to deal with plastic pollution.

- Central Banks have historically targeted particular industries and guided finance into uses where it would not otherwise go. One of the easiest ways to do this is to insist on disclosure. This could be made a requirement of central banks as the head of the financing institutions.

- Industrial policy. Substitutes for plastic are already growing and are almost worth a third of the plastic trade. These are categories in which many developing countries have a comparative advantage already. To promote substitutes in the markets, it is necessary to align industrial policies.

- We must align all these levers to achieve desired outcomes from plastic pollution and development perspectives. A starting point for action is the common but differentiated treatment while keeping in mind that a wide range of potential sources of revenue that can be harnessed and redirected to ending plastic pollution are available.

Closing

Carolyn DEERE BIRKBECK

- Financing is out there. If we use the right instruments and governments deploy the right policies, we have the capacity to shift finance in the right direction.

- This session has painted a holistic picture of all aspects of financing that are relevant to generating the systems change and just transitions required to end plastic pollution.

- The panel interventions have served as points for reflection on the kinds of provisions and approaches that might be needed in the treaty.

Documents

Links

- Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee on Plastic Pollution

- Plastic Pollution | TESS

- Redirecting Financial Flows to End Plastic Pollution | UNEP-FI

- Ten Key Messages to Align Financial Flows with the Objective of Ending Plastic Pollution | UNEP-FI

- Convention on Plastic Pollution – Essential Elements – Finance | EIA

- Towards Plastics Pollution INC-4

- International Cooperation on Plastic Pollution | Plastics and the Environment Series